Maria Balshaw

The director of the Whitworth Art Gallery and Manchester City Galleries has been a driving force behind the city’s cultural renaissance

Apollo Award Winners 2015

Personality | Artist | Acquisition | Exhibition | Digital Innovation | Book | Museum Opening  Award sponsored by Sophie Macpherson Ltd

Award sponsored by Sophie Macpherson Ltd

Maria Balshaw can pinpoint the ‘transformative’ moment when she realised her future lay in the visual arts. On a Saturday afternoon in 1991, when Balshaw was in her early 20s, she visited the Chisenhale Gallery in East London to see Cornelia Parker’s landmark installation Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View. For the work, Parker had asked the British Army to detonate a garden shed, before collecting the detritus from the explosion and suspending it from the ceiling of the gallery, as if time had frozen still at the moment of the blast. ‘It was absolutely the most exciting thing I’d ever seen,’ Balshaw tells me. ‘Seeing that exploded shed – that’s when I thought, yes, this is what I’ve been looking for.’

It’s hard to imagine Balshaw (a self-confessed ‘feisty Northern woman’) being rattled by anything, but when she finally met Parker years later, her nerves came close to failing her. At around the time that plans for the redevelopment of the Whitworth Art Gallery, the Manchester institution she has directed since 2006, were getting off the ground, Balshaw was invited to a dinner at London’s Serpentine Gallery. When she found out she was to be seated next to her artistic hero, she freely admits that she was ‘almost too nervous to speak’.

Nonetheless, the two got on well, and at the end of the evening, Balshaw couldn’t resist the temptation of asking Parker whether she would be interested in creating a project at the Whitworth. ‘I was impressed by Maria,’ Parker remembers. When she raised the prospect of working together, ‘I thought: Great! She made it impossible to turn down.’ The result was Parker’s major mid-career retrospective at the Whitworth this spring, the inaugural exhibition at the newly reopened gallery. As early as February, it was widely tipped as one of the shows of the year.

Everyone I speak to applies certain qualities to Maria Balshaw. Parker is not the only person to mention her ‘sense of energy and excitement,’ nor is she the only one to identify the remarkable ‘can do’ attitude that has characterised her dual tenure as director of the Whitworth and the Manchester Art Gallery. Yet improbable though it now seems, Balshaw never saw herself in such a role prior to taking the reins at the Whitworth. ‘When I was headhunted for the Whitworth directorship, I thought, I can’t possibly do that job!’ she tells me over the phone from Beijing, a city she is visiting with other directors involved in the Plus Tate network.

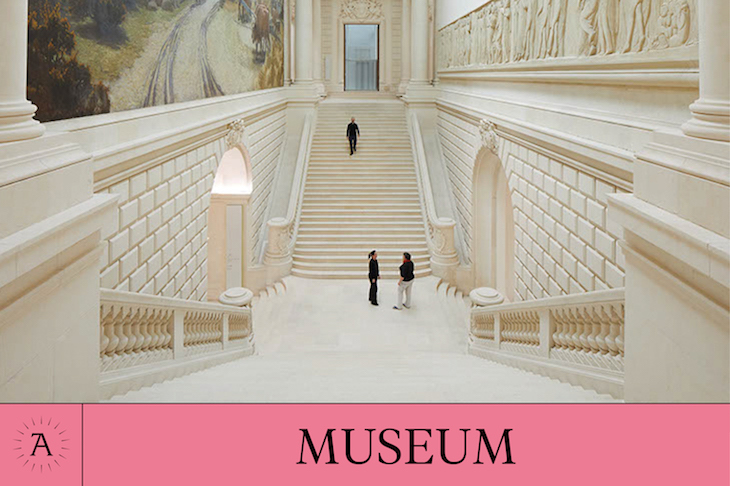

The offer, however, was simply too good to pass up, and that much-lauded ‘can do’ spirit kicked in. In the nine years since accepting the job, Balshaw has proved herself more wrong than she could have known. This February, after a 16-month closure for renovation and extension works, the new-look Whitworth reopened to blanket praise. The old red-brick gallery on the Oxford Road, a distinctly unglamorous thoroughfare that divides the districts of Rusholme and Moss Side, had been transformed into a truly state-of-the-art space.

New windows flood the Whitworth with light, and an enormous illuminated text piece by Nathan Coley beams the message ‘GATHERING OF STRANGERS’ out into the park. At the front, what used to be a rather sorry looking car park is now a sculpture garden, while an iron fence that once closed off the museum from the adjacent Whitworth Park has been removed in a gesture as symbolic as it was aesthetic; this, it seems, is the Whitworth fully opening itself up to the local community. The museum is part of the University of Manchester, but every member of staff I speak to is at pains to stress that it is a space for everyone.

All signs suggest that the £15 million that went towards the refurbishment was money well spent. When I visit on a miserable Tuesday afternoon in November, the gallery is packed, its airy new café at full capacity. The Whitworth has seen record visitor numbers this year, and in the month after its reopening saw average footfall increase fivefold, according to the Manchester Evening News. In truth, though, the Whitworth redevelopment is just the latest stage in a long-term project that has aimed, ever since Balshaw took the helm, at giving Mancunians what she refers to as a ‘genuine sense of ownership’ over their gallery.

Helen Stalker, curator of fine art at the gallery, puts its radical change of path over the past decade into perspective. Before Balshaw arrived, she says, the Whitworth was ‘very quiet – a very good museum, but fairly closed off’. This last attribute is not an evaluation any visitor would be likely to offer now.

None of this has gone unnoticed. When the Whitworth was named as the Art Fund’s Museum of the Year 2015, the award was well deserved. Was it a vindication of Balshaw’s somewhat unconventional attitude to running it? Yes, she says, ‘but we’d only just opened – it was chaos! We found out the judges’ visit was going to coincide with an event by some young people who were developing their own programme.’ Candidly, she admits that she had no idea whether or not it was going to work, and seriously considered cancelling the event – which featured input from, among others, a local ‘Grime’ band – but ultimately went with her instincts. ‘We had to go ahead with it! Trusting everyone involved was, of course, the right thing to do.’

As it turned out, the event was extremely well attended, and went ahead without a hitch. Perhaps it was this bold, anything-goes approach that led the chair of the judges and Art Fund director Stephen Deuchar to state that the Whitworth ‘truly feels like a museum of the future’.

You could be forgiven for a degree of scepticism about such claims. But any doubts I may have had vanish within moments of walking into the Whitworth. At reception, I’m greeted by a member of staff who can’t hold back from gushing enthusiastically for his workplace. I’ve barely been in the Whitworth for five minutes, yet already I’ve been treated to a crash course in the museum’s permanent collection, facilities, and layout. ‘We do our best to cultivate the staff’s interest,’ Balshaw says (we speak the day after my visit). ‘We give them time to react to the shows themselves, making everyone feel like it’s their Whitworth.’

It isn’t just the staff who are invited to get more involved with the gallery. ‘People put their own ideas into art,’ Balshaw says. ‘It’s important to share knowledge generously.’ At this, she excels. The gallery’s open-plan layout means that displays flow into one another, yet the narrative specific to each hang never becomes convoluted. You see a display of artist Richard Forster’s photo-realistic drawings segue flawlessly into a cluster of watercolours from the Whitworth’s permanent collections, with only a partial wall divide separating both from an exhibition on art and textiles. ‘We could never use the Whitworth’s collection to try and tell the History of Art,’ Balshaw admits, ‘so we showcase the real areas of strength and try to suggest connections.’

Perhaps it’s unsurprising that she avoids a traditional art-historical approach. Balshaw stresses that her background of study makes her something of an outsider in the museum world. ‘When I started, I didn’t know how museums had always done things,’ she insists, ‘so I was able to question things a bit more.’ She studied English at Liverpool University, before going on to do an MA in Critical Theory and a DPhil in African-American Visual Culture at the University of Sussex.

She took up her first academic position as a lecturer at Northampton University in 1994, and three years later moved to the University of Birmingham as a research fellow. In 2002, Balshaw made the jump from academia to the UK government’s newly launched Creative Partnerships programme, working as national director of the Birmingham-based initiative to bring art organisations into the country’s classrooms. After two years, her achievements at Creative Partnerships led to her selection as a fellow for the inaugural Clore Leadership Programme, an organisation designed to foster and exchange new ideas about cultural leadership.

Axel Rüger, now director of Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum, met Balshaw at the interview stage, and was immediately impressed. ‘Maria was one of the most energetic people on the programme,’ he explains. ‘She was ambitious, in the best sense of the word.’ It was only a matter of time before the headhunters sought her out for the Whitworth job, but even at that stage, it wasn’t clear to Rüger where his Clore contemporary would end up. ‘No, I didn’t expect that,’ he says, ‘but I wasn’t surprised.’

Balshaw’s appointment at the Whitworth came a year before the first edition of the Manchester International Festival, whose former director Alex Poots she has collaborated with extensively. The joint impact of a revivified Whitworth showing work by international stars like Marina Abramović, Douglas Gordon, and Anri Sala and a major biennial event has brought on something of a cultural renaissance in Manchester, now unquestionably Britain’s second city for culture.

Even so, Balshaw admits that there are still problems with the UK’s arts culture, and the way in which London still dominates creative discussion. ‘I am immensely proud to be serving Manchester,’ she says, making reference to the city’s grandeur and fiercely held civic pride. However, ‘It’s hopeless to compare yourself to London,’ she says. Ideally, she believes the German model – where cities ‘have their own flavour’, culturally speaking – is the best thing to aspire to for regional British arts organisations. But competition with the capital, she readily states, is senseless.

Even so, she is at pains to add that as far as museums go, the country has become less London-centric, and cooperation between institutions – the Plus Tate network being a case in point – is flourishing. At any rate, Manchester’s comparatively small arts sector often works to the city’s advantage. ‘London has a lot to learn from what institutions do here,’ she says, adding that it can actually be more difficult for organisations in the capital to share resources and ideas in the same way that Manchester’s tightly knit arts community does.

Even after she accepted her second, concurrent directorship at Manchester City Galleries (‘I made it clear that there was no way I was leaving the Whitworth’) in 2011 and a place on the board of Arts Council England in 2014, Balshaw somehow still finds the time to get involved elsewhere. It’s clear both from Balshaw and her colleagues that her involvement in the city’s cultural boom spreads far wider than the job descriptions.

Perhaps the most intriguing prospect that lies ahead is the £110 million arts centre, the Factory, currently under development at the old Granada Studios site as part of the government’s ‘Northern Powerhouse’ project. Balshaw (who is also Manchester’s cultural attaché) and Alex Poots were instrumental in developing plans for the new space. They presented their proposal to the Chancellor last year, and ‘Rather surprisingly, George Osborne thought it was an excellent idea.’ The Government has now put £78 million towards it.

Nevertheless, Balshaw has felt the pinch of the current climate of arts funding in Britain. For museums, ‘There is never going to be enough money ever,’ and cuts have only aggravated the situation. When the coalition government abolished the UK’s Regional Development Agencies shortly after coming to power in 2010, even Balshaw was temporarily at a loss. ‘I went home and put my head on the kitchen counter and groaned,’ she says.

Yet before too long, she had made up for the shortfall in funding for the Whitworth extension. ‘The project was strong enough to survive,’ she explains, attributing the success to the ‘clarity’ of the original vision. ‘Maria can be quite gung-ho,’ Cornelia Parker explains, adding that her way of fundraising is ‘very direct’. In Parker’s experience, it pays off; from what she’s observed of donors in Manchester, ‘they’d do anything’ for Balshaw.

And small wonder. Under her watch, both the Whitworth and the Manchester Art Gallery have struck the nigh-on impossible balance of becoming accessible institutions that somehow avoid condescending to their visitors. There are no gratuitous displays of academic language, but nor is there any hint of the infantilising approach to art history that so often creeps into major museum shows. ‘You can sound scholarly and intelligent without sounding like you’re writing a PhD,’ Balshaw says. ‘There is no place in the 21st century for institutions that cater for an elite’.

Balshaw is on her way to dinner, having left a conference late. Time is running out, but I want to know one more thing: with such an astonishing track record over the past decade, what can we anticipate from her in the next one? She laughs. ‘Expect to be surprised.’

Digby Warde-Aldam is a writer and art critic based in London

Apollo Award Winners 2015

Apollo Award Winners 2015

Personality | Artist | Acquisition | Exhibition | Digital Innovation | Book | Museum Opening

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.