Paris is having a Bonnard moment this spring. ‘Pierre Bonnard, Painting Arcadia’, opened at the Musée d’Orsay on 17 March. And on Sunday 29 March an auction of Bonnard’s work fetched 5.4 million euros at Osenat auction house in Fontainebleau. The paintings and sketchbooks came from the collection of Antoine Terasse – an art historian, critic and Bonnard’s great-nephew, who passed away in 2013.

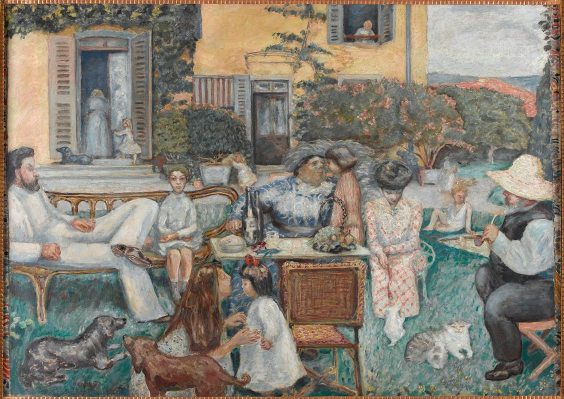

L’Après-midi bourgeoise (1900), Pierre Bonnard © Musée d’Orsay, dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt © ADAGP, Paris 2015

The Terrasse family (sans Antoine who wasn’t born until 1928) feature in the middle section of the Orsay’s exhibition in L’Après-midi bourgeoise (1900). It is a strangely naïve painting of family leisure, the different figures appear almost as caricature. According to art critic and founder of La Revue Blanche, Thadée Natanson, (whose 1906 portrait also features), this painting ‘is where Bonnard really started to find himself’.

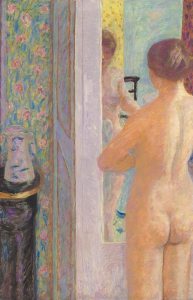

La Toilette (1914, retouched 1921), Pierre Bonnard © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski © ADAGP, Paris 2015

His style may have shifted over time, but Bonnard’s themes remain constant: intimate scenes of domestic interiors and gardens. One section of the show explores Bonnard’s bathroom paintings – a wonderful collection of nudes, enamel, mirrors and windows in compositions that have been cropped and flattened, challenging our perception of space. Elsewhere, we’re introduced to Bonnard’s Normandy garden and the côte d’Azur. In Paysage Normand and Le Pommier fleuri, the untamed foliage verges on abstract. Le Jardin, painted in the South, has a similar effect but with the saturated colours of the Mediterranean.

The exhibition is bookended by Bonnard’s decorative works. It opens with Japanese-inspired compositions from the 1890s, including panels from the Orsay’s collection, a sumptuous red screen from Marlene and Spencer Hays’ collection, and four canvases of apple-picking, reunited from the Orsay’s collection, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and Pola Museum of Art in Japan. The final section, ‘Et in Arcadia ego’, brings together commissioned decorative schemes. For his friend and muse Misia, Bonnard created a series showing figures cavorting in Baroque-classical outdoor settings, like a bacchanalian Versailles. La Méditerranée, a triptych commissioned by Ivan Morozov for his residence in Saint Petersburg, depicts a more domestic paradise: the bright warm Mediterranean colours; women and children relaxing in pools of shade. Bonnard’s aesthetic and indeed the very idea of ‘Painting Arcadia’, are a welcome change from the more tenebrous aesthetic explored in recent Orsay exhibitions (Sade, Van Gogh/Artaud, Gustave Doré, Dark Romanticism…).

A set of photographs gives an insight into Bonnard’s personal life. Photography was less an artistic pursuit for Bonnard than a chance to takes pictures of friends and family (Vuillard features regularly). The jaunty title of this section, ‘Clic clac Kodak’, has proved prophetic. Culture minister Fleur Pellerin snapped one of the canvases in the show and posted it to her Instagram feed, explicitly flouting the museum’s strict no photography rule. Her actions led to the photo ban being lifted by the Musée d’Orsay, in line with other French museums and the Ministry of Culture’s photography charter. Merci, Bonnard.

‘Pierre Bonnard: Painting Arcadia’ is at the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, until 19 July.

Related Articles

Should photography in museums be allowed? (Danielle Thom)

Snap Happy (Thomas Marks)

Discovery of desire: Sade at the Musée d’Orsay (Matthew McLean)

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?