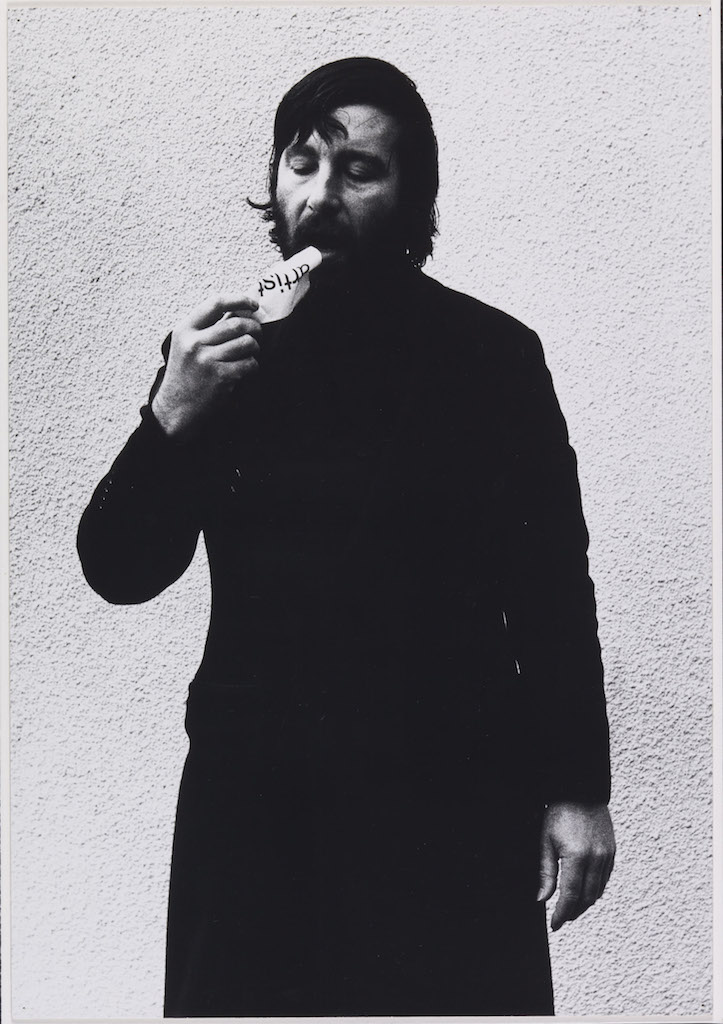

In his 1971 work Art as an Act of Retraction, Keith Arnatt eats his words. As part of Tate Britain’s current exhibition ‘Conceptual Art in Britain 1964–79’, it’s a reminder of how, during this period, artists consumed a lot of theory and then spat it back out. This was a time when young artists, rejecting the purity of modernist painting and sculpture, privileged ideas over objects (in 1966 John Latham famously chewed to a pulp US critic Clement Greenberg’s arch modernist text Art and Culture). Joseph Kosuth summed it up: ‘Art as Idea as Idea’. Yet as interesting as these ideas might be, they don’t necessarily make for a thrilling exhibition.

Art as an Act of Retraction (detail) (1971), Keith Arnatt. © Keith Arnatt Estate/ DACS, London

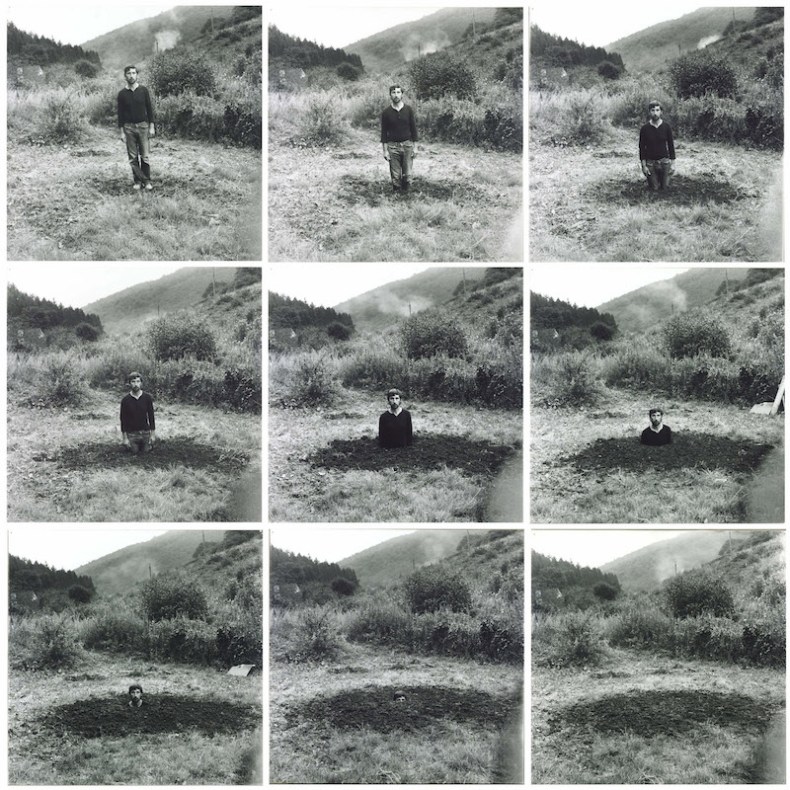

Self-Burial (Television Interference Project) (1969), Keith Arnatt. © Keith Arnatt Estate / DACS, London

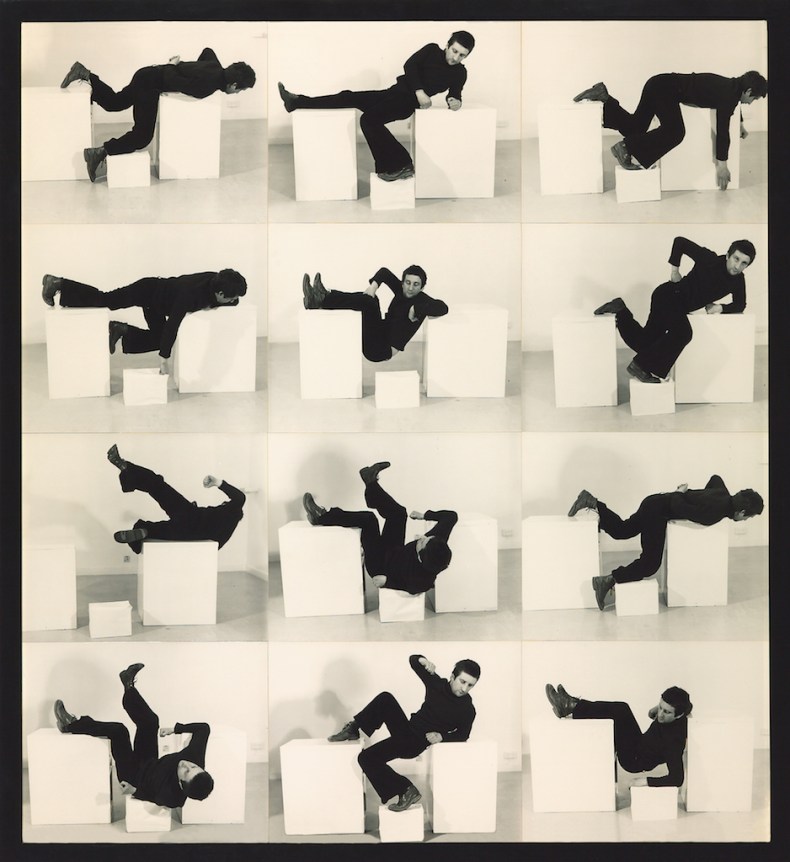

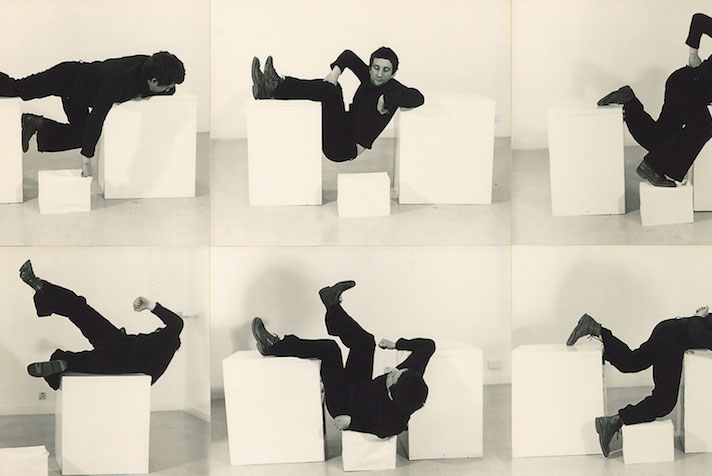

Arnatt’s work, however, is fun. Composed of 11 black and white photographs it shows the artist putting crumpled bits of paper into his mouth. Another work, made in 1969, sees Arnatt bury himself over a series of nine photographs; standing tall at the beginning, he eventually disappears feet-first into the muddy ground. A serious comment on the disappearance of the art object this might be, but the near-final image of Arnatt’s head peeping just above the ground is fairly amusing. Elsewhere, also in a series of photographs, Bruce McLean battles awkwardly with a plinth in his comic attempts to take Henry Moore down a peg or two.

Pose Work for Plinths 3 (1971), Bruce McClean. © Bruce McClean. Courtesy Tanya Leighton Gallery, Berlin

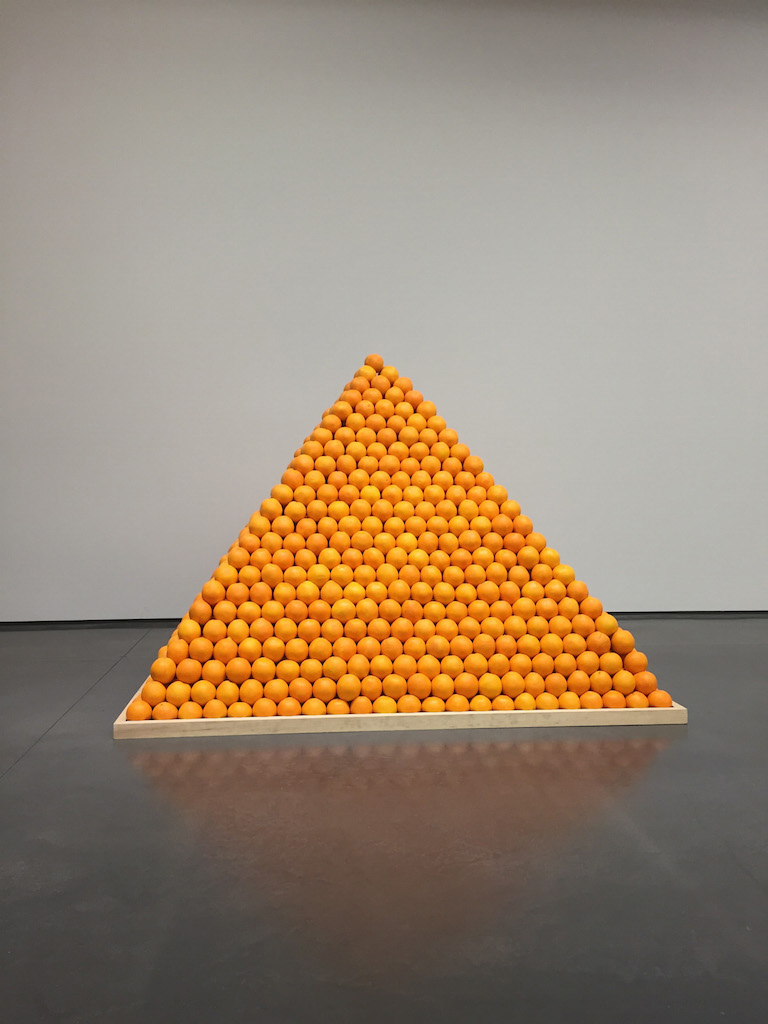

Despite being black and white, these works are the main moments of colour (aside, perhaps, from Roelof Louw’s pyramid of real-life oranges) in an exhibition that is remarkably dense and text heavy. This is perhaps unavoidable: conceptual art is an art of the document, of lists and indexes, of data, and statements of intent written on bits of paper. Vitrine after vitrine, laid out like Donald Judd’s minimalist boxes, house old exhibition leaflets, letters, photographs and event invitations. Not to mention the vast amount of space dedicated to Art & Language’s tiresome treatises (there are a massive 26 works by the British group on display here). As a result, the show looks like an archival experiment. Arnatt’s 1968 photograph, Invisible Hole Revealed by the Shadow of the Artist, emerged from the artist asking himself: ‘How visual does visual art need to be?’ It’s a question that overshadows this exhibition, where the lack of an art object has clear implications for an art exhibition. How do you find an aesthetic in the archive?

Soul City (1967), Roelof Louw. © Roelof Louw

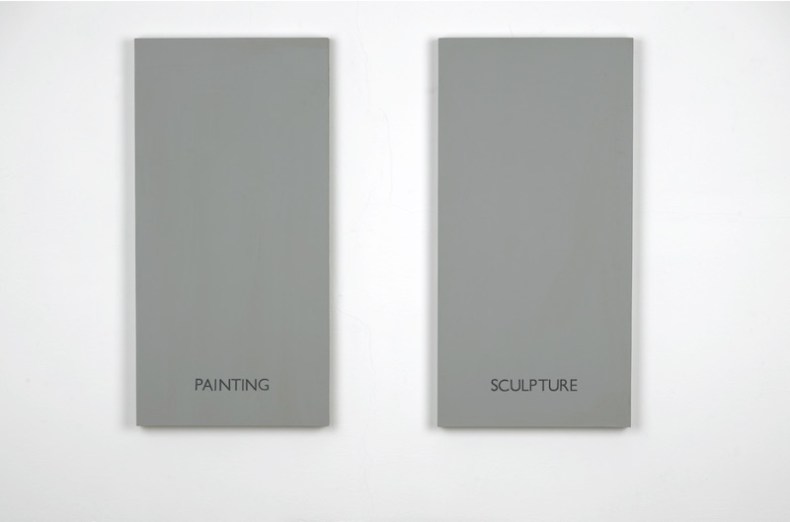

Yet in some ways, the question of visuality is pointless: conceptual art deliberately shifted the focus from looking to reading and so quite rightly there’s a lot to read here. It was, in fact, this linguistic turn that gave conceptualism its force; language became the tool with which to question the very nature of art. Inspired by structuralist philosophy, conceptual art frequently revels in language games and textual tangles: as Art & Language’s Painting/Sculpture (1966–67) highlights, this was an art that used words rather than images. Michael Craig-Martin’s An Oak Tree (1973), consisting of a glass of water sat on a glass shelf, exists in the slippery space between word and image and blows open any pre-held ideas about what form art might take. This is art that requires a leap of faith from the viewer.

Painting/Sculpture (1966–67), Art & Language (Terry Atkinson and Michael Baldwin). © Courtesy Mulier Mulier Gallery, Belgium © Art & Language

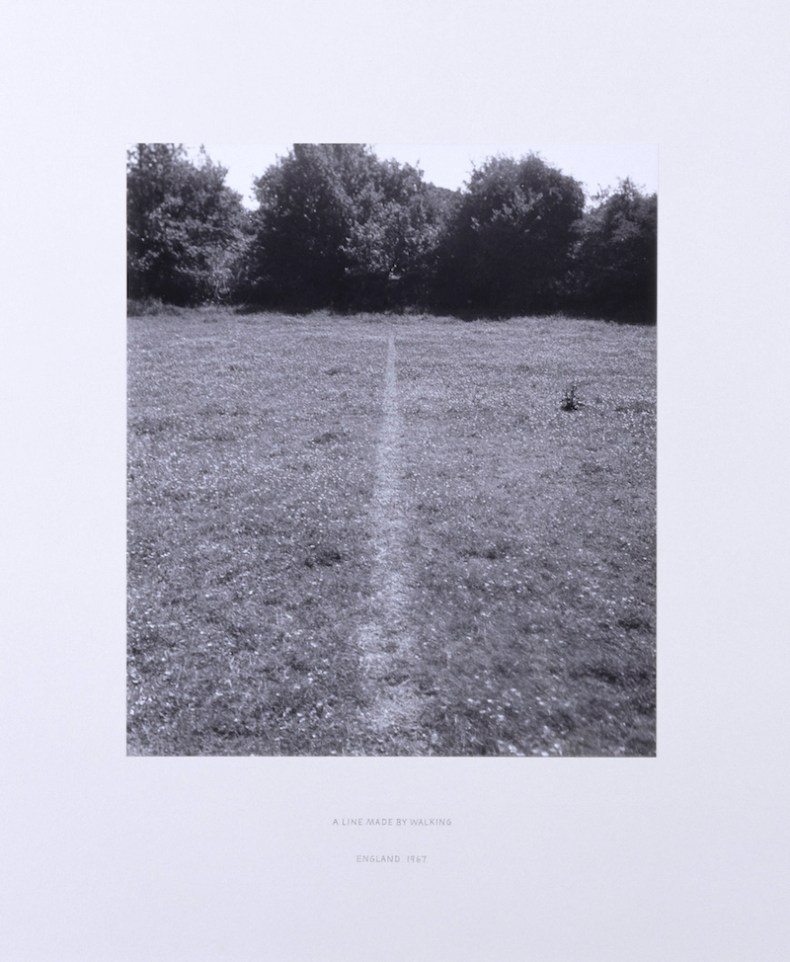

Tightly curated by Andrew Wilson, the exhibition does give a strong sense of the rupture caused by British artists at this time – that a mound of sand could be art (Barry Flanagan), or that it could take the form of a sound recording (David Tremlett), radically extended Duchamp’s earlier avant-gardism. Such works, along with those by Richard Long and Hamish Fulton, also stand out as examples of the turn towards process-based, durational art. Long’s beautiful A Line Made By Walking (1967) gains its potency from the act of walking itself, from the experience of being in the landscape – it’s also an important precursor of performance art. Long’s interest in impermanence, in the traces that an artist leaves behind, finds echoes in Arnatt’s Art as an Act of Retraction. After all, the artist doesn’t actually eat his words but is about to, creating a tension between what is said and unsaid. What, Arnatt also seems to ask, is left behind?

A Line Made by Walking (1967), Richard Long. © Richard Long / DACS, London

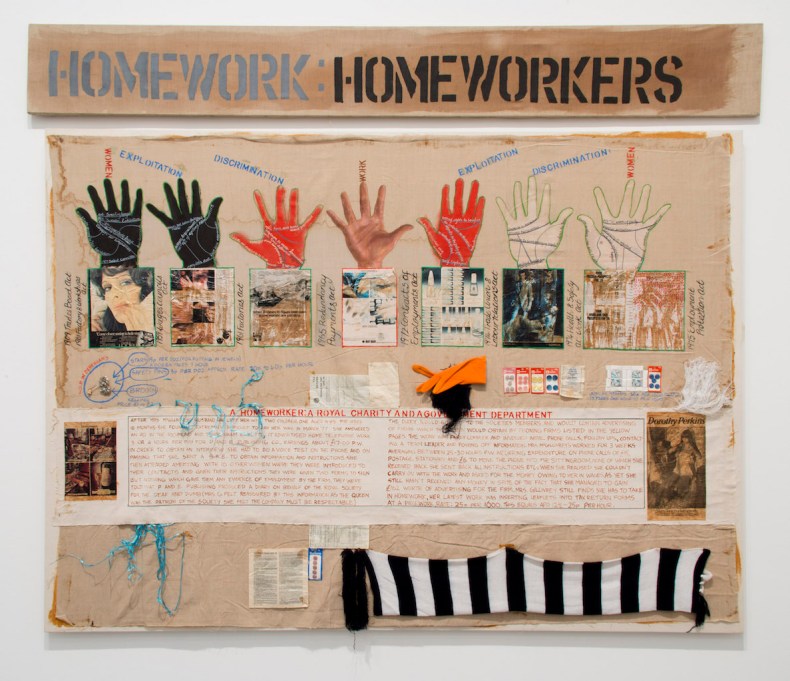

Despite its attempts to expand the parameters of art, conceptualism can often feel insular and circular. The most successful room in the Tate show is the final one, which looks more obviously outwards – although it does feel slightly at odds with the rest of the exhibition. By its very nature, conceptualism is rebellious, critical of dominant modes of production and strongly anti-commercial; it also has a social conscience. Stephen Willats’ Living with Practical Realities (1978), made up of three large photographic panels, follows the life of Mrs Moran, an elderly woman living alone in a west London tower block. A study in social isolation and economic depravity, the work’s rational, spider-diagram objectivity is what gives it such emotional force. Mary Kelly’s Post-Partum Document (1975) analyses the artist’s changing relationship with her son over a six-year period. It’s a more private meditation whose approach has links with Margaret Harrison’s Homeworkers (1977), which charts the wider struggle of women. The canvas is haphazardly covered with items made by women – buttons, stamps, gloves – and lists their cheap retail price alongside. Interspersing these aspects of labour with 1970s adverts for make-up and slimming products makes the artist’s point abundantly clear.

Homeworkers (1977), Margaret Harrison. © Margaret F. Harrison

That the show ends in 1979, when Thatcher came to power, is not coincidental. In today’s unstable political climate, the questions raised – about politics and aesthetics, and about art’s social function – resonate beyond these gallery walls.

‘Conceptual Art in Britain 1964-79’ is at Tate Britain, London, until 29 August.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?