The journeys we make, read and learn about all influence way we view the world and the people in it. Recognising this, a new exhibition at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery brings together a diverse array of objects, from East Asian scrolls to recent photographs, to look critically at how travel (in this case, to Asia) is represented in art. How have journeys been recorded over the centuries, and what can these records tell us today?

‘A Traveler’s Eye: Scenes of Asia’ is the work of seven experts. We asked each of them to pick a favourite item from the display, and to explain how these records of other people’s journeys speak personally to them.

Stephen Allee

Associate curator of Chinese painting and calligraphy (Chinese scrolls)

Travelers on the Road to Shu (c. 1494–1552), style of Qiu Ying. Ming dynasty Chinese handscroll: ink and colour on silk

I love the colour and the sense of activity among the many different groups of travellers; several upper class women riding horses and wearing red hoods, merchants who have pulled the loads from their mounts for a rest while one horse rolls on the ground in relief, and the families with children in tow.

Debra Diamond

Curator of South and Southeast Asian art (organising curator)

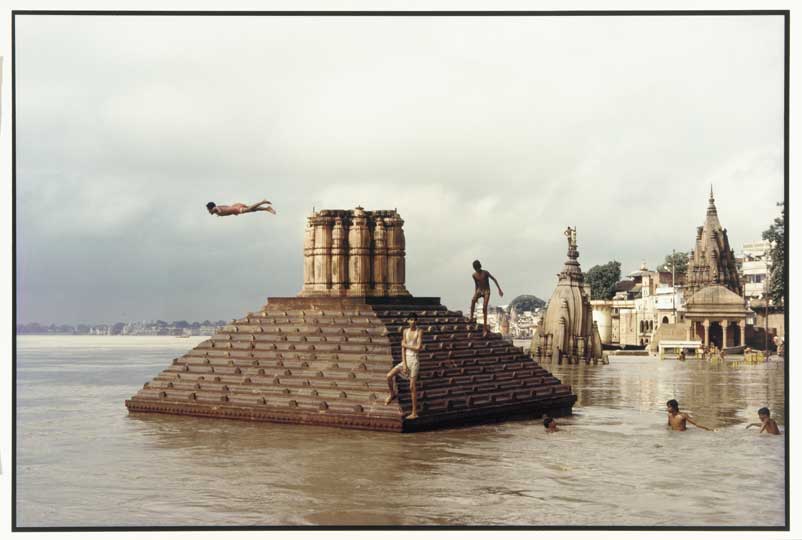

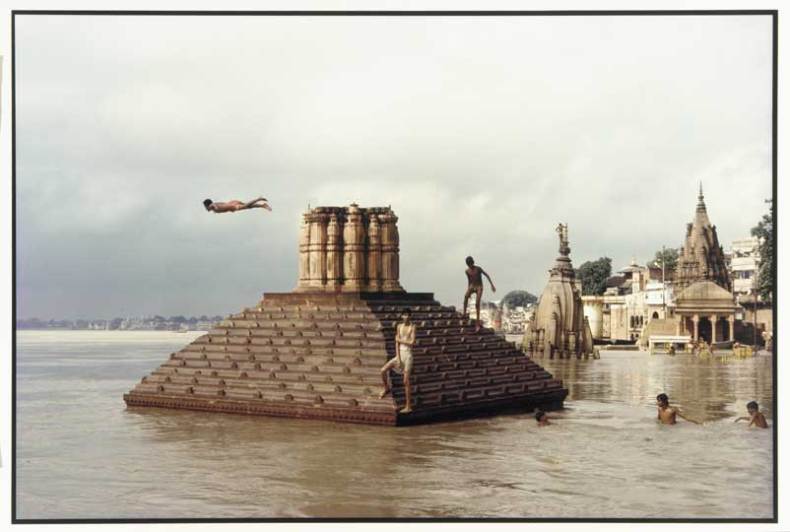

Swimmers and Diver, Scindia Ghat (1985), Raghubir Singh. Chromogenic print on Kodak Ektacolor paper

I love it because he captured the decisive moment, the joy and beauty of flying through the air from the peak of a temple.

David Hogge

Head of the Freer and Sackler Archives (Herzfeld and Freer archival materials)

Selection of 39 stones gathered at Yi River by Charles Lang Freer, 1910

Freer’s rocks. Hands down. It’s so surprising that a foremost collector of Asian art masterpieces should fill his pockets with river stones, bring them all the way back from central China, have custom wooden stands made for each one, and have each of them accessioned into his museum as works of art. It gives us a glimpse of something entirely unanticipated about Freer. The hard-nosed captain of industry had a sentimental streak.

Carol Huh

Associate curator of contemporary Asian art (Raghubir Singh photographs)

Excavation of Samarra: men crossing a river (1911–13), Ernst Herzfeld. Modern print from original collodion

A number of archeologist Ernst Herzfeld’s photographs offer stunning views of sites in Iran and Iraq. Although considered documentation, closer inspection of Herzfeld’s prints and negatives suggests that he was attentive to the subtle manipulation of light and composition, resulting in romantic views of a seemingly infinite frontier. His photographs, like this panoramic image of men crossing a river in Samarra (Iraq), often provide not only topographical context, but also hint at a desire to convey the ineffable grandeur of the desert landscape.

Nancy Micklewright

Interim Head of Public and Scholarly Engagement (postcards)

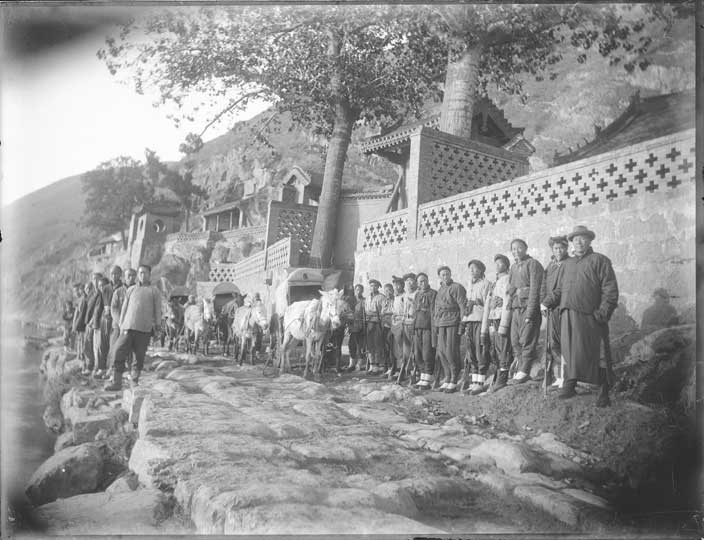

Chinese workers at Longmen (12 November, 1910), Yütai. Silver gelatin photographic print

This lovely silver gelatin print, a view of the buildings where Charles Freer stayed in Longmen, gives us a sense of the remote landscape which Freer found so compelling on his last trip to China. The rocks that he brought back as souvenirs (displayed in the same gallery) were probably collected here from the bank of the Yi River, just visible at the left edge of the photo. What I especially love about this image is imagining a trip where one traveller is accompanied by such an enormous team of assistants, drivers, cooks, and guards! It’s a far cry from how we travel today.

James Ulak

Senior curator of Japanese art (Japanese screens and prints)

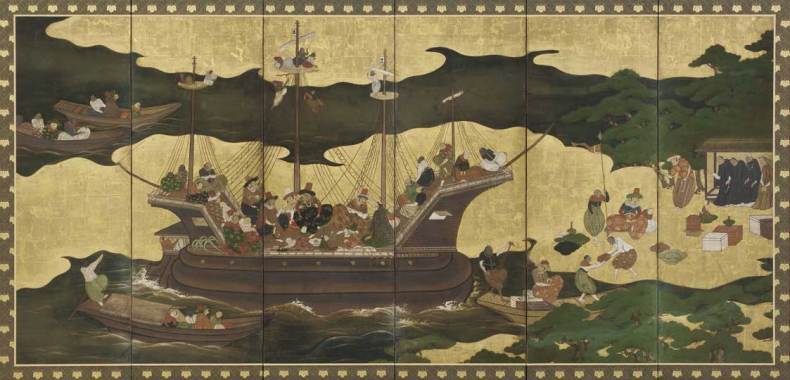

‘Southern Barbarians’ on Japan’s Shores (17th century), Japan. Edo period pair of six-panel folding screens: ink, colour and gold on paper

My favourite work in the exhibition is the pair of six-panel screens featuring the arrival of Portuguese merchants and missionaries at a Japanese port. Titled Southern Barbarians in Japan, this is one of over 90 known screens of this subject produced mostly in the first half of the 17th century by Japanese artists. The term ‘namban’ or ‘southern barbarian’ was a Japanese designation for the Europeans who arrived in Japan via Southeast Asia.

These paintings have particular personal resonance because works of this genre were probably the first Japanese paintings I ever saw. Used to illustrate a school boy textbook that described the great age of European exploration, the images valorised the heroic risks taken by the great Iberian explorers to advance knowledge and spread Christianity to exotic and far-flung corners of the world. A rich tapestry of detailed activity, these paintings are a 17th-century equivalent of a photograph of men landing on the moon; they seem to capture that moment of a first encounter. A lifetime and four decades of specialised study have intervened. While the simplistic notions that these are images of European triumphalism have been overturned, the works continue to reward close study for their complexity and variety.

Most importantly, we realise that these are images created for Japanese by Japanese. They were surely not intended to capture a moment of European glory nor even conceived as a kind of Japanese ethnographic record (although a good deal of useful information is contained in the images). It is now suggested that the images celebrate a prosperity enjoyed by Japanese merchants at that time and, more than anything, suggest a fluidity of international trade occurring in this period among many cultures. The dated notion of a European journey to the ‘edge of the earth’ has been replaced with a more plausible narrative of exploration. We now know that in unfamiliar waters, the Portuguese were assisted by indigenous pilots who plied areas that were their backyards. For example dark skinned figures high in the masts of the ship may have been such navigators from Oman. As well, Japanese merchant ships sailed far into the waters of Southeast Asia. Exploration was a two-way street and ‘unknown’ was a very relative term.

Ehon Sumidagawa ryōgan ichiran (Illustrated book, Both Sides of the Sumida River at a Glance) (c. 1805–6), Katsushika Hokusai

Ann Yonemura

Senior associate curator of Japanese art (Japanese screens and prints)

Ehon Sumidagawa ryōgan ichiran (Illustrated book, Both Sides of the Sumida River at a Glance) (c. 1805–6), Katsushika Hokusai. Woodblock printed: ink and colour on paper

My favourite object is Hokusai’s three-volume Ehon Sumidagawa ryōgan ichiran (1804), a set of full-colour woodblock printed books illustrated with continuous images of both sides of the Sumida River, which flowed through Edo (now Tokyo) into Edo Bay. Hokusai’s irrepressible inventiveness inspired him to illustrate three volumes like a handscroll, continuing the scenes from sheet to sheet and volume to volume. The images include charming landscapes and river views and lively crowded scenes of urban and suburban work and pleasure.

‘The Traveler’s Eye: Scenes of Asia’ is at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C., from 22 November–31 May 2015.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?