Two nude studies of women face each other across the gallery space (or at least they would, except both are faceless, tapering into abstraction at the neck). The first is slim and lithe, her arms held out behind her as she leans backwards into a stretch. Her skin is as tense and tight as the lines that describe it, her body as finely balanced as the composition. The second figure reclines, relaxed and a little unkempt. The living warmth and heaviness of her body is suggested in the deepening red scuffs of the artist’s chalk in the hollows of her armpit and belly button, and around her groin.

The first drawing is by Eric Gill, the second by his friend and rival Frank Dobson – two modern British sculptors brought together at Daniel Katz Gallery under the title ‘True and Pure’ (until 24 June). Gill is arguably better known today, but the real emphasis here is on Dobson, whose drawings Katz has been collecting for many years, and whose profile the gallery hopes to revive. In the 1920s, Dobson was seen as a pioneering figure in the British avant-garde, as Roger Fry’s ringing endorsement in 1925 makes clear: the Bloomsbury critic described his work as ‘true sculpture and pure sculpture…almost the first time that such a thing has been even attempted in England.’ So it’s Dobson who has the direct claim to both qualities in the current exhibition’s title: Gill is here, it turns out, as a ‘contemporary reference point’.

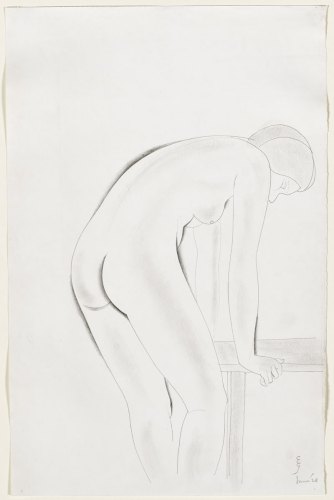

Standing nude (1928), Eric Gill

I’m not sure an artist like Gill can serve as a reference point for anything much, other than himself. His intense, idiosyncratic style divided critics in his day, and the revelations about his sexual life that emerged after his death have cast his entire oeuvre – including the obsessive, intense studies displayed here – in a complex and troubling new light. The work by Gill in this exhibition is every bit as startling and unexpected as Dobson’s, not so much a reference point as a counterpoint to the other artist’s work.

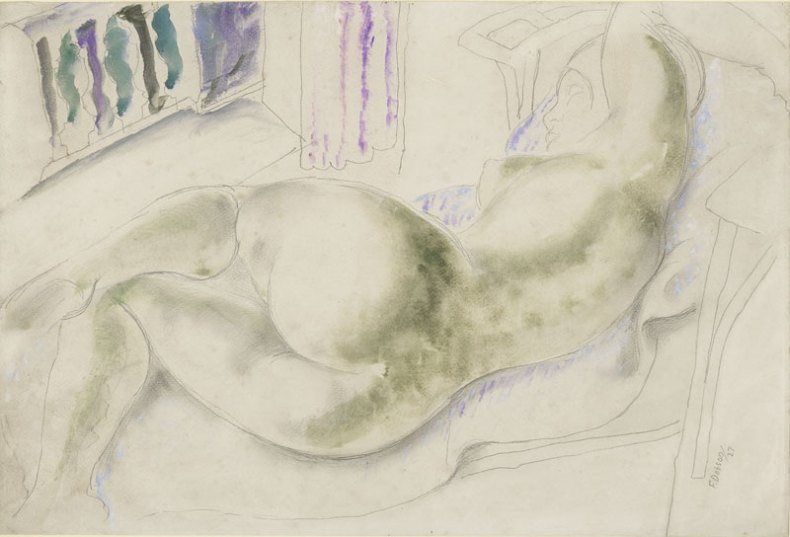

Levée (1945), Frank Dobson

It is interesting, for instance, to consider the artists’ differing choice and use of materials, in both drawing and sculpture. Gill started out as a letter-cutter and monumental mason: you can see as much in the precision of his sharpened chalk lines, and the self-contained clarity of his subjects. In his drawings, relief carvings and his work in the round, he used the same hard, thin edges to describe key features, smoothing out and polishing over the rest. Dobson trained as a painter, and brought a painter’s flair to his sketches, revelling in sweeping gestures and adding blocks of watercolour over or around his subjects. He was also a skilful modeller, and it is fascinating to see his red chalk drawings – created by layering and smudging, moving his medium around on the page – alongside some of his small figurative terracottas in the same warm hue. A little more unexpected is the recurrence of mossy or pale green tinges in many of his figure drawings, which could be a nod to the translucent shades of his stone and marble sculptures. (Dobson’s drawings were generally intended as studies for three-dimensional work, whereas Gill would often produce standalone works on paper.)

Reclining Nude with Mediterranean Window (1927), Frank Dobson

Each artist’s drawings seem to anticipate and inform their sculptural style, though as ever it is dangerous to oversimplify. Dobson produced hard stone carvings of great precision and polish, too (a reclining woman in marble, buffed to a shine and on loan from the Courtauld Gallery, is a highlight here), while Gill’s carved torsos have a disarming softness to them. Nonetheless, there’s a certain rough-and-tumble feel to Dobson’s work that consistently distinguishes it. Like many artists of the time, he grappled obsessively with the human form, exaggerating and simplifying his models’ features to create something more universal. But while Gill and others would often slip into a rather hieratic style, Dobson’s works retain a sense of living, breathing humanity. In the middle of the 20th century this probably worked against him – Dobson’s reputational decline is linked to the rise of (slightly) younger sculptors such as Henry Moore who were willing to push their abstractions further. Now, though, it’s just refreshing.

‘True and Pure, Frank Dobson and Eric Gill drawing from life’ is at Daniel Katz Ltd., London, until 24 June.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?