Turners, Dürers, or Bellinis

Do not spring from dry Martinis.

Goya’s genius, Rubens’ powers

Did not stem from whiskey sours.

Fumy brandies, potent ciders

Make no Holbeins, make no Ryders.

Alcohol’s ingurgitation

Is, in short, no substitution

For creative inspiration

Or artistic execution.

Guzzle vino

Till you’re blotto

Splotches will remain but splotches.

Perugino,

Ingres, Giotto

Were not born of double Scotches…

When the humorist Arthur Kramer published these lines under the title ‘Homily for Art Students’ in the New Yorker in 1946, he mixed up a potent brew of historical beliefs about art and drinking. The dry Martinis, whiskey sours and double scotches belong to the 20th-century booze-hound, particular about his drinks and able to afford quality liquor. The reader is invited to imagine Dürer and Rubens taking a booth in an uptown cocktail bar. The anachronism implies a continuity between the myths of hard-drinking artists from different eras: as if the beer-swilling painters of the Dutch Golden Age, the absinthe-addled wretches of 19th-century Paris, the tough guys of the New York School, liquored-up and rowdy at the Cedar Tavern, and several generations of British artists, stumbling out drunk in the late afternoon from Soho’s Colony Room Club, could all be imagined in some timeless bar- room. In disavowing the link between artistic inspiration, heightened creative powers, and the use of alcohol, the poem attests to how firmly the myth was established in the popular mind. By the time Kramer wrote his poem, the myth had become self-fulfilling.

The earliest drunkard painter of legend is Frans Hals (1582/83–1666). The image of Hals as an alcoholic and wife-beater was established by Arnold Houbraken’s colourful biography in The Great Theatre of Dutch Painters (1718–21). It claims that Hals was ‘filled to the gills every evening’, and that when Anthony van Dyck came to meet him in Haarlem he was not at home, and ‘it took a long time to scour the taverns for him’. Hals’ reputation was fixed. Two hundred years later, on meeting a former lover of his who had returned from service in the First World War, Somerset Maugham remarked: ‘You may have looked like a Bronzino once, but now you look like a depraved Frans Hals.’ The suggestion is of a face like Hals’ The Merry Drinker (1630), rosaceous, worn and worldly. Houbraken’s life of Jan Steen (c. 1626–79) has a similar tenor to that of Hals, with many of its anecdotes focusing on Steen’s other work as a brewer and innkeeper. Recent scholarship has shown the myth of the drunkard painters of the Dutch Golden Age to be largely without foundation – a product of an incautious identification of artists with their subject matter, and a misunderstanding of just how respectable and dignified brewers were as civic figures. Houbraken is open about his inversion of the biographical fallacy, whereby he constructs the life from the nature of the work, writing that ‘Steen’s paintings are as his way of life and his way of life as his paintings’. The phrase ‘a Jan Steen household’ is still proverbial in Dutch for a home in rowdy disarray, after his many scenes of disordered domestic and public houses. In his autobiography Praeterita (1885–89), John Ruskin described how he inherited the prejudice, which he would never shake off, that ‘the old Dutch school’ were ‘sots, gamblers, debauchees, delighting in the reality of the alehouse more than in its pictures’. As Seymour Slive has written, ‘the fallacious idea that an artist who depicted merry drinkers must needs have been a tosspot himself dies hard’.

Many Dutch drinking scenes try to have their cake and eat it, by offering themselves as allegories of moderation – take Steen’s Wine is a Mocker (1663–64 – while revelling in the possibilities for sensuous excitement, stirred flesh and dynamic composition that drunken misrule presents. When Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525–69) paints The Battle Between Carnival and Lent (1559), carnival is clearly coming out on top within what we might call the libidinal economy of the painting, even while any respectable burgher knows he should side with Lent. When Jan Vermeer (1632–75) paints an enigmatically interrupted bourgeois idyll such as The Girl with the Wine Glass (1659–60), the centre of consciousness is the goosey girl, part naive and part knowing, who delights in being chatted up by the roguish gander, even as an allegory of Temperance looks on disapprovingly from the stained-glass window.

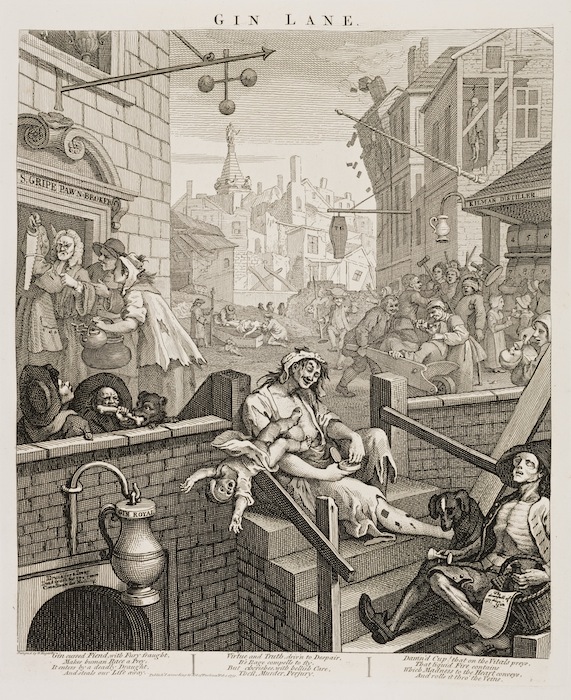

Perhaps the grimmest image in the annals of morally instructive booze art comes a century later, when William Hogarth (1697–1764) shockingly portrays the destructive effects wrought by cheap gin on the London poor in Gin Lane, which makes a pair with Beer Street (both 1751). The focus is on the addled wretch who sits on the top step leading down to a gin cellar. She picks at her snuff box with a cracked smile, her head tilted to the side, oblivious to the wardrobe malfunction which has left her sagging breasts exposed. Her bare legs are marked with syphilitic sores. Her infant boy tries to gain her attention with a last-ditch gadarene back-flip to his death in the gin-puddled stairwell. Below her is a horribly emaciated, possibly dead pamphlet-seller, accompanied by a sad black dog. The title of his pamphlet is ‘The Downfall of Mrs Gin’.

Once the idea of the artist as bohemian had solidified in the mid 19th century, a large number of artists emerged who truly were tosspots. An article in the British Journal of Addiction in 1954 pictured a hideous drunken composite: ‘the late 19th-century Bohemian monster, the aristocratic dwarf who cut off his ear and lived on a South Sea Island’. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin were just three painters of the period whose heavy drinking contributed to an early death. Where beer and wine had been the chosen poisons of 17th-century Lowlanders, 19th-century French painting had a new magic potion: absinthe. Toulouse-Lautrec’s pictures were described by Gustave Moreau as ‘painted entirely in absinthe’; he would stop at every bar in Montmartre in order to étouffer un perroquet (choke a parrot), in the slang of the period; and he had a specially made hollow walking-stick which held an emergency half-litre stash of absinthe and a tiny shot glass. Absinthe was a boon to the colourist: in Van Gogh’s L’Absinthe (1887), the drink’s yellow-green picks up the murky, submarine tones of the sad view through the window; the brown wooden panelling of the walls looks like the side of a drunken boat becalmed in a sea of lonely alcoholic despon-dency. In both Édouard Manet’s The Absinthe Drinker (1859) and Edgar Degas’s L’Absinthe (1876) the pale greenish glass adds a sick glow to the murkily degraded metropolitan modernity (although in the former the glass of absinthe may be a later addition to the canvas).

‘Hip Hip Hurrah!’ Artists’ Party at Skagen, 1888, Peder Severin Kroyer (1851–1909). Goteborgs Konstmuseum, Sweden

In contrast to these doomed and gloomy 19th-century scenes, Hip, Hip, Hurrah! (1888) by Peder Severin Krøyer (1851–1909) presents drunkenness as sheer joyous revelry. Depicting an al fresco drinking party of the Scandinavian artists known as the ‘Skagen Painters’, after the fishing town in the northern-most tip of Denmark to which they were drawn by the quality of the light, the painting is a study in impressionistic light effects. The low early-evening sun plays across the overhanging leaves of the grove where the table is set up, throwing dappled reflections onto the men’s flushed faces and their fair hair and beards (Krøyer himself stands third from the left). The champagne flutes they toast with cast these light effects into relief. Each golden cone is held up as if it were a bar of light or a taper; and the golden foil around the long necks of the five empty champagne bottles picks up this detail. By their rosy cheeks and bulbous noses we might guess that these men are heavy drinkers, but there is no sense in the painting of the dark side of drinking, unless by a sort of negative implication. For Thomas Cooper Gotch, the English painter who was inspired by Krøyer’s painting to pay a visit to Skagen in 1889, ‘the good humoured gentle high-spirited type of people’ shown here, ‘fair headed with open countenances’, represent ‘the climax of mirth and good fellowship’.

When Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo in March 1889, to address the concern doing the rounds that ‘instead of eating enough and at regular times, I kept myself going on coffee and alcohol’, he didn’t deny it, but instead claimed it was needed for his work: ‘I admit all that, but all the same it is true that to attain the high yellow note that I attained last summer, I really had to be pretty well keyed up. And that after all, an artist is a man with his work to do…’ Such Romantic ideas about the link between drunkenness and continuing creativity have been made less credible since the 20th century by widespread acceptance of ‘alcoholism’ as a disease, and then by increased understanding of the nature of alcohol dependency. Olivia Laing’s book The Trip to Echo Spring: Why Writers Drink, published in August this year, has brought the prevalence of alcoholism among 20th-century American writers to fresh attention, with its moving account of the ways in which addiction shaped and disfigured the lives of Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Tennessee Williams among others. There is just as much to be said about why painters of the period drank. ‘I was interested while I was working on The Trip to Echo Spring in the hard-drinking New York School poet Frank O’Hara, and so this led me into a brief immersion in the world of the Abstract Expressionists’, Laing told me. ‘The tales from the Cedar Tavern tend to be presented in a comic light – bar brawls, doors ripped from hinges – but I suspect that many present were not fully in control of their drinking. It’s a scene interestingly poised between pleasure and addiction.’ If bohem-ianism was a 19th-century European invention, it was perfected in 20th-century New York. For Elaine and Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Joan Mitchell, Grace Hartigan, Franz Kline et al, to be a heavy drinker was the signature mode of how to be a bohemian: a way of not being bourgeois, while enacting an idea of the artist which was cherished by the bourgeoisie on whom your livelihood relied. At the height of his fame, Pollock’s destructive acting-out was a form of performance art; people who had read of his boozy intensity in Time magazine would come like tourists to buy him drinks and watch the troubled genius overturning tables, assaulting women and getting into fights. In these years, as Elaine de Kooning put it, ‘The whole art world became alcoholic.’

The same thing was happening in London: Francis Bacon (1909–92), who late in life claimed to have been ‘drunk since the age of 15’, could be found every afternoon in Soho’s pubs and drinking clubs, and was a founder member of the famous Colony Room Club in 1948 – a private members’ club that got around the restrictive licensing laws of the time to allow drinking from lunchtime through to night. Lucian Freud, Michael Andrews and Frank Auerbach, among others, were also regulars, with several of the Young British Artists of the 1990s following in their footsteps. In 2008, the year the club closed down, Will Self commemorated it in the novella Foie Humain (in the collection Liver) as ‘the Plantation Club’, with Bacon turned into Trouget, ‘a world-famous painter…known to his fellow members merely as “the Tosher”’, who props up the bar every day, ‘erect in his habitual, tightly zipped, Bell Star motorcycle jacket,’ issuing ‘gnomic utterances’. The tone of the novella is at once elegiac and appalled at the waste and addiction, knowing that Trouget’s acidic one-liners will be forgotten in the blur of ‘three decades of barring and bitching, belching and kvetching’.

Since the New York School were primarily abstract painters, there is no direct address to the subject of drink in their works, although the urgency of brushstroke and facture often seem to be invoking an internal drama of intoxication, disinhibition and released authenticity. But maybe the quintessential comment on the mid-century relation between American boozing and art-making are Jasper Johns’ bronze Ballantine ale cans of the 1960s, which cut out the medium of alcoholic inspiration altogether to present two beer cans as the work itself, cast in timeless bronze with their commercial labelling painted on.

In truth, alcoholism does not vary a great deal between different classes of people, artists or not. The great, humbling discovery of AA meetings for artists or intellectuals is that the patterns of maladaptation their drinking causes – the lying, the cheating, the avoidances – are the same as those of the commonest Joe. The reason that artists’ drinking is of more interest than the drinking of, say, doctors or house painters, is that artists’ drinking is reflected in, and inflects their work in ways that form part of its meaning. Drink, drinking and drunkenness have also provided subject matter almost from the earliest recorded history of art. From Attic vases to Tlaxcalan altar paintings, the psychoactive and physiological properties of this chemical have everywhere been celebrated, wondered at, and moralised about. And alcohol is a central theme in ancient, classical and religious works – think of treatments of the drunkenness of Noah by Bellini or Michelangelo, Cranach’s drunken-ness of Lot, or innumerable images of the Marriage at Cana, or of Bacchus and confreres.

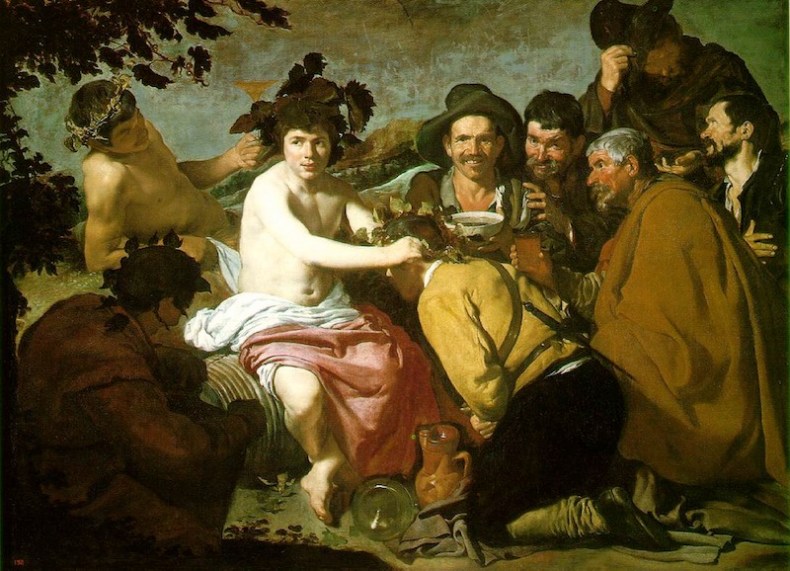

Perhaps the work which best straddles mythological and secular representations of drinking is the 1628 painting by Velázquez (1599–1660) which is most commonly known as Los Borrachos (‘The Drunkards’), a nickname it acquired in the 19th century after it had moved to the Prado from the Royal Palace in Madrid. Earlier inventories referred to it by titles such as The Triumph of Bacchus or Bacchus and his Companions. The shifting titles point to the enigma of the painting. What is the nature of this scene? The six figures in various postures to the right-hand side of the canvas seem to be Spanish peasants, judging by their plain clothing and their tanned, lived-in, character-actor features. They look like a convivial crew of boozers, their faces intelligent and expressive. They could be the al fresco Southern counter-parts to a Dutch tavern scene of happy misrule. Two of them smile at the viewer. They seem to belong in a genre painting, but Bacchus, the focal point to whom the eye is drawn, seems to have swooped in from a history painting; he is far more brightly lit than anything else in the picture, and not in any way that could be explained naturalistically with reference to a light source. What does it mean to have Bacchus convening a drinking party of 17th-century Iberian peasants? The painting has been interpreted many ways: maybe it is parodic, mocking the peasants by putting them in the god’s company; or maybe it is a burlesque of mythological paintings; maybe this is a young man merely pretending to be Bacchus, possibly in some sort of jest at the royal court; maybe it is an allegory of prudence or moderation; or maybe it is a straightforward depiction of a bacchic revel, in which we should overlook the anachronism of the peasants, rather like Shakespeare’s Romans kitted out in Renaissance dress. In any case, it is a highly suggestive canvas in which the gift of drink, its transformative capacity for deliverance and camaraderie, is the driving libidinal force.

When I quoted lines from Arthur Kramer’s ‘Homily for Art Students’ at the head of this article, I omitted his final couplet. After cautioning aspiring artists against the idea that heavy drinking will turn them into the next Holbein or Giotto, the poem enters a caveat: ‘Nor, alas, will full sobriety / Whisk you into their society.’ Both the destructive compulsions of drink and its gifts of fun and comradeship, both the feelings of creative unloosening it provides and the dependency on it that forms in many people, are bound up in the long association between alcohol and artistic inspiration – an association which is not likely to weaken any time soon. When Damien Hirst was asked why the YBAs still gathered at the Colony Room Club, years after its heyday, his reply was simple: ‘It’s because artists like drinking.’

BP Spotlight: Art and Alcohol runs at Tate Britain until Autumn 2016

Click here to subscribe to Apollo

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?