Of all the subjects to focus on in the National Gallery’s collection – from seductive Venuses to glorious sunflowers – the choice of the humble tree is hardly the most riveting. Yet it is trees that dominate George Shaw’s exhibition ‘My Back to Nature’, which consists of works created in response to the collection. Since the start of 2014, Shaw has been the National Gallery’s associate artist, with special access to the collection. Shaw moved into the Gallery’s studio for one week out of every three, arriving every day at 8am so that he could draw from the collection for a couple of hours before it opened to the public.

The Assassination of Saint Peter Martyr (probably c. 1507), Giovanni Bellini. © The National Gallery, London

Why, then, is Shaw so fascinated by trees? On the one hand, Shaw has always been interested in depicting familiar subjects: when he was nominated for the Turner Prize in 2011 it was for his retrospective ‘The Sly and Unseen Day’, which featured paintings of the housing estate in Coventry where he grew up. Similarly, the trees in ‘My Back to Nature’ are from an area he often explored during his teenage years – the neglected woodlands near his home.

The Triumph of Pan (1636), Nicolas Poussin. © The National Gallery, London

On the other hand, Shaw’s focus on trees is a specific response to the gallery’s collection. In the exhibition catalogue, Shaw writes about a number of historic works that depict scenes taking place in woods. Giovanni Bellini’s The Assassination of Saint Peter Martyr (c. 1507) presents the woods as a place of dark and fearful happenings; Titian’s Diana and Actaeon (1556–59) and The Death of Actaeon (1576) has the woods as the forbidden world of the gods; and Poussin’s The Triumph of Pan (1636) reveals the woods as a site of licentious revelry. In his own paintings, Shaw is also enthralled by the idea of the woods as a place for transgression, but his approach to depicting this is quite different due to the complete absence of people in his work. Instead, Shaw suggests life by the pieces of rubbish, graffiti and porn magazines that people leave behind.

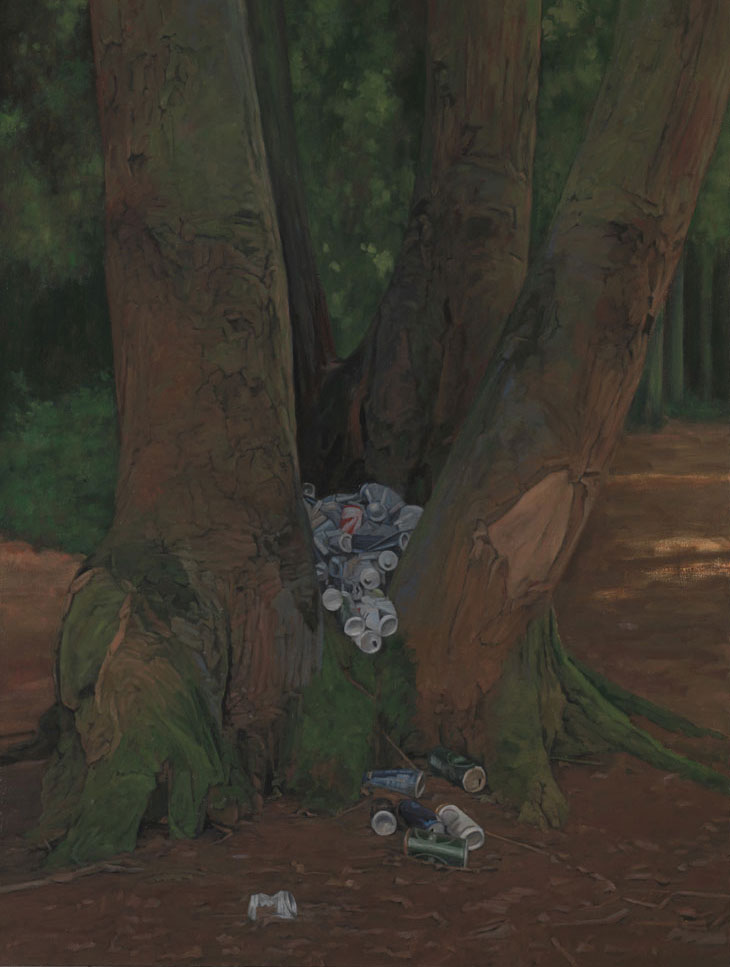

The Tree of Whatever (2015–16), George Shaw. Courtesy the artist and Wilkinson Gallery, London

The Old Master (2015–16), George Shaw. Courtesy the artist and Wilkinson Gallery, London

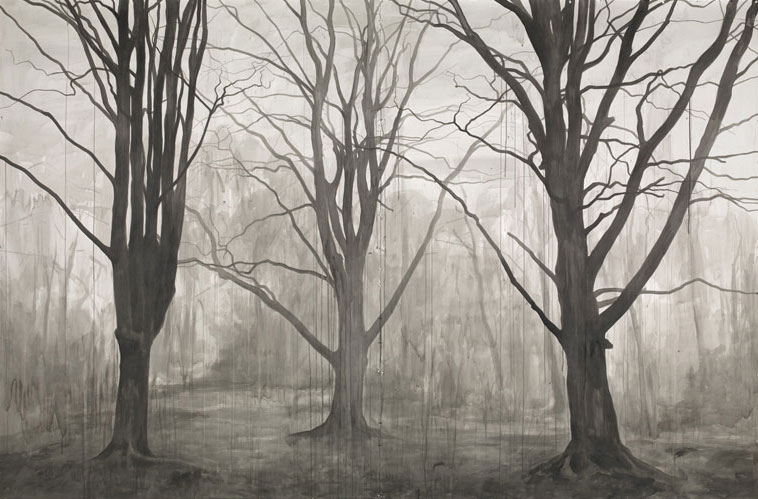

The vandals who presumably left the used cans in The Tree of Whatever (2015–16), the old tarpaulin in The Living and the Dead (2015–16) and the phallic graffiti in The Old Master (2015–16) had little respect for these trees. The same is not true of Shaw. Captured in a dingy twilight, his trees are not especially stunning, but the artist revels in the rich details of their branches; their texture, their crevices, and the twists of their unpredictable forms. His ink studies for Verso (2014) and Recto (2014) not only magnify their lumps and bumps, but also explore how the light subtly reflects off their bark. The trees in Study for Hanging Around (Landscape without Figures) (2014) have an ethereal quality, too. Set against a cool, pale sky, their leafless branches twizzle out with alluring delicacy. Shaw outlines the trees clearly, but he also allows long drips of ink to dribble down the paper, reminding us that this is a painting and these trees are unreal.

This is not Shaw’s only suggestion of the otherworldly. His large painting of The Rude Screen (2015–16) shows what appears to be a sheet of tarpaulin hanging over a branch. While the title seems to refer to the flimsy curtain that Actaeon draws back revealing the naked goddess Diana in Titian’s Diana and Actaeon (1556–59), this blue material is more reminiscent of the collection’s many portrayals of the Virgin Mary. The folds and creases of the sheet are as meticulously painted as any cloak worn by this holy figure. Shaw may appreciate these trees more than the vandals, but he does not condemn their rubbish as ugly.

Diana and Actaeon (1556–59), Titian. © The National Gallery, London

The Rude Screen (2015–16), George Shaw. Courtesy the artist and Wilkinson Gallery, London

The used cans, porn magazines and plastic sheeting in ‘My Back to Nature’ put the remnants of sordid happenings centre stage. But are Shaw’s paintings more or less crude than those that inspired him? The artist has explained that the longer he spends with the National Gallery’s collection, the more he realises that ‘it’s all sex, death, bowls of fruit and flowers, and the odd landscape.’ So if Bellini can put murder at the centre of his wood, and Poussin can put sex in his, then Shaw’s subtle suggestions of what went on in Coventry the night before start to look considerably tamer. Perhaps this is exactly what Shaw is trying to portray: that sense of quiet reflection that we feel when examining the National Gallery’s paintings is often in spite of the blatantly rousing scenes that are taking place within them, right in front of our eyes.

Hanging Around (Landscape without Figures) (2012), George Shaw. Courtesy the artist and Wilkinson Gallery, London

‘George Shaw: My Back to Nature’ is at the National Gallery, London, until 30 October.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?