Joseph Cornell rarely left New York State, content to shuttle back and forth between Manhattan and his home in the suburb of Flushing in Queens. As ‘Wanderlust’, the title of the Royal Academy’s Cornell retrospective underlines, Cornell took mental rather than physical voyages, savouring the bittersweet quality of anticipated and imagined travel, rather than the experience itself.

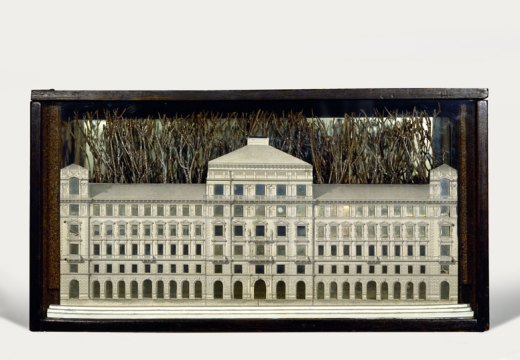

This beguiling premise makes for a scaffold on which to hang Cornell’s assemblages, which frequently incorporate allusions to travel, such as sections of maps, the names of European hotels steeped in faded grandeur, and old suitcases as receptacles for collections of ephemera. Cornell gathered these found objects on his trips into New York, where in 1931 he also encountered Surrealist collages at the Julian Levy Gallery on Madison Avenue.

Habitat Group for a Shooting Gallery 1943, Joseph Cornell © The Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation/VAGA, NY/DACS, London 2015

Inspired, he began to create his own two and three dimensional collage works, often housed inside glass-fronted wooden boxes. In Object (Compass Set) from 1940, multiple compasses are nested inside custom-made holes within a box; when removed, collaged sections of botanical drawings are revealed. Untitled (Music Box) of around 1947 is covered with stamps, while his Soap Bubble Sets are often framed by friezes of constellations. In these works, and many others on display, Cornell invokes the promise of travel only to suppress it.

The curators have been careful to ensure that this focus on imagined travel doesn’t obscure a wider view of Cornell’s creativity. Although Cornell has often been cast as an art-world outsider and recluse, there is another, more nuanced perspective. Cornell formed an important conduit between pre and inter-war Surrealism, and the experimental avant-garde of the 1950s and ’60s in the US. He counted among his admirers and acquaintances the poet Elizabeth Bishop, who dedicated poems and her own assemblages to him, and visual artists such as the abstract-expressionist Robert Motherwell to the performance artist Carolee Schneemann.

‘Wanderlust’ opens with the film Gnir Rednow (1965), which is composed by splicing together outtakes from the filmmaker Stan Brakhage’s The Wonder Ring (1955) and completed by Larry Jordan. Cornell himself had asked Brakhage to make The Wonder Ring in order to document views from the 3rd Avenue elevated train before it was dismantled. The inverted images of Gnir Rednow, which record apartment-blocks and street signs flashing by under the daggers of light created by the L-train’s lattice-mesh architecture, document a vanished time and place. The film is a meditative collaborative vision in which an everyday urban experience is infused with mystery and poetry.

Object (Soap Bubble Set) 1941, Joseph Cornell © The Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation/VAGA, NY/DACS, London 2015

The exhibition cites other creative relationships, notably in a 1947 letter from Cornell to Dorothea Tanning, which is embellished with collage fragments; the inclusion of the assemblage Untitled (Multiple Cubes) of 1946–48 in the largest room of the exhibition, unites a number of Cornell’s hotel-themed works. Untitled (Multiple Cubes) differs markedly from the Victorian influences and peeling paintwork of the majority of the hotel assemblages; its white grid offers a bleak abstracted invocation of multiple identical rooms that bears out the impact of Cornell’s meeting with Mondrian in the 1940s.

Indeed, you get the sense that Wanderlust has many more stories up its sleeve than can fit into its main narrative arc. The Royal Academy’s Sackler Wing provides a relatively small exhibition space. A bit more room might have offered ways of avoiding the bell-jar effect that can descend when the focus is on Cornell’s vitrines. There are several such moments in the show, notably through the inclusion Cornell’s film work, and the acknowledgment of his wider artistic milieu. Equally, the inventive use of atmospheric film meditations on individual works, shown as part of the displays, offers a far more fitting way of ‘enlivening’ the works by Cornell originally intended to be handled and touched than replicas might have done.

It feels greedy to ask for more, especially when this is the first major show of Cornell’s work in the UK. It is a surprisingly belated one given his influence, significance and appeal. But perhaps my hunger is a fitting testament to an artist – and exhibition – concerned with the insatiability of curiosity.

‘Joseph Cornell: Wanderlust’ is at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, until 27 September and at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, from 20 October–10 January 2016.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?