From the May issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here

Why do museums recreate landmark exhibitions, installations and performances, and what can we learn from these restagings?

Last year, the Hepworth Wakefield filled its recently opened project space, situated upriver from David Chipperfield’s iconic building in a reclaimed warehouse, with a mass of car tyres. The sea of rubber was an eloquent statement on post-industrial malaise in its own right, but the exhibit came with a long history as well. Yard, by the US artist Allan Kaprow, was first displayed in 1961 at the Martha Jackson Gallery in New York. Its Hepworth appearance was one of many reinventions of the work over the years: an example of how institutions have now become open to the recreation of past installations and exhibitions.

The influences fuelling the current appetite for reinstalling, re-exhibiting, and restaging are complicated. They range from pedagogic and archival ambitions, through to the transformation of art museums into venues for mediums such as film, video, performance art and dance. While ‘repetition’ implies faithfulness to an original, ‘recreation’ and ‘reinvention’ hint at the inevitable, even desirable changes that creep in with each iteration. At their most productive, such returns can challenge our conventional definition of a ‘historic’ exhibition, and prompt us to create alternative histories.

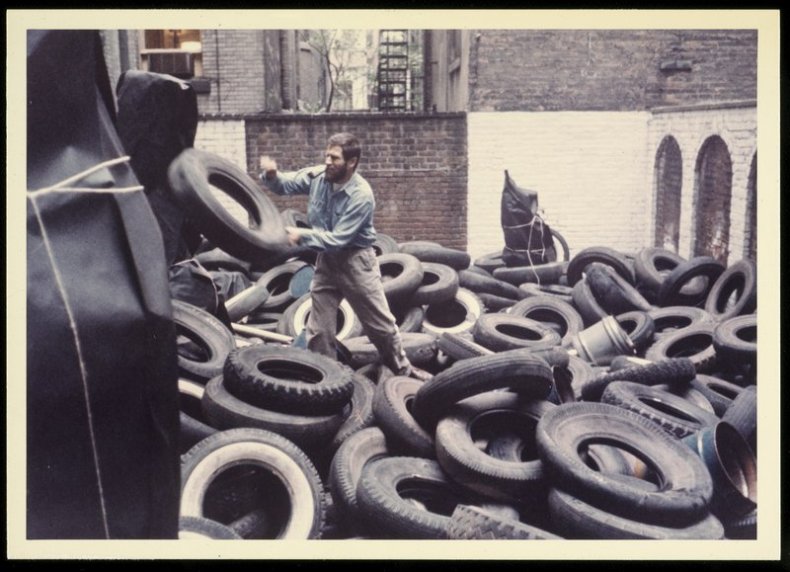

Allan Kaprow installing the first version of ‘Yard’, in the sculpture garden of Martha Jackson Gallery in New York, 1961. Courtesy Allan Kaprow estate and Hauser & Wirth. Photo © Ken Heyman

Tate’s recent exhibition programme has contained several notable instances of recreation – and its educational value. Tate Modern’s 2014 Kazimir Malevich show partially recreated a section of ‘The Last Exhibition of Futurist Painting 0.10 (Zero-Ten)’, held in Petrograd during 1915. Guided by the one surviving photograph of this exhibition, with which Malevich unveiled his vision of Suprematist art, the curators positioned the 1929 version of Malevich’s Black Square in the upper corner of one room. With this gesture, Malevich claimed the space normally housing a Russian icon for his painting. Although Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall is no stranger to experimental installations, the Malevich rehang underlined how subtle alterations in established methods of display can still retain a radical charge decades after their original occurrence.

Overlapping with the Malevich show in London, Tate Liverpool’s ‘Mondrian and his Studios’ followed the recreation impulse even further by structuring its display around a full-scale replica of Piet Mondrian’s Paris workspace. While in the wrong hands this might have produced a recherché period room, the effect was a vivid realisation of the architectonic aspirations that Mondrian had for his painting, and for the Neo-Plasticist movement. Through recreation, ‘Mondrian and his Studios’ could convey Mondrian’s understanding of abstraction as a vital part of everyday life, rather than a rarefied exercise in formalism.

Installation view showing the recreation of Piet Mondrian’s (1872–1944) Paris studio at Tate Liverpool, 2014. Image courtesy Tate Liverpool. Photo: Roger Sinek

On walking into Tate Modern’s 2014 Richard Hamilton retrospective, audiences were plunged into a meticulously curated rehang of Hamilton’s 1951 exhibition ‘Growth and Form’, which was organised to coincide with the Festival of Britain. As they moved further into the Tate show, visitors found themselves in a resurrection of the iconic ‘fun house’ installation Hamilton collaborated on for the 1956 ‘This is Tomorrow’ exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery. Across the Thames, the Institute of Contemporary Arts extended the retrospective by redisplaying Hamilton and Victor Pasmore’s 1957 installation, An Exhibit.

By going to all this trouble, rather than simply providing archival photographs of the earlier exhibitions in a vitrine, the curators showed how Hamilton’s experiments directly contributed to innovations in exhibition design, and allowed audiences to trace his thought-processes across several aspects of his work. Hamilton’s career testifies to the importance of installation as an artistic practice, and its effect on the presentation and reception of art in the latter part of the 20th century. Pieces like An Exhibit and Yard are pre-programmed for being transposed to other places: they are responsive to their sites, but not inherently site-specific. This flexibility, combined with the increasingly blurred roles of artist and curator, has been central to the growing enthusiasm for revisiting whole exhibitions.

Such recreations are, often by default, institutional projects. They demand dedicated archival sleuthing, agreement from artists’ estates and copyright holders, and levels of technical labour that only large organisations can provide. The scholarly endeavour involved is frequently exemplary. The process offers a dynamically different way of conducting research, and of bringing it to a much wider audience than an academic publication could.

A key precedent in this respect is the 1991 exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, “‘Degenerate Art”: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany’. Its curator, Stephanie Barron, staged a room-for-room rehang of the infamous 1937 exhibition ‘Entartete Kunst’ (Degenerate Art)’, organised by the National Socialist Party in Munich as a condemnation of modern art, exploring how the display was used to construct an ideology of racial ‘purity’ and its propagandist effects. In cases such as this, the rationale for reinvestigation seems clear, but it nonetheless remains vital to engage with questions about the reasons and criteria governing such returns, as it is here that their most interesting and provocative implications can be found.

Some projects wear their revisionist criteria on their sleeves. During 2014, the Jewish Museum in New York staged ‘Other Primary Structures’, a two-part update of their 1966 exhibition ‘Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculptors’, which established what would become the canon of minimalist sculpture. Curated by Jens Hoffmann, ‘Other Primary Structures’ sought to rewrite the history of this moment by expanding the original 1966 show beyond its myopic Anglo-American focus, instead featuring sculptures made during the same period by artists from Latin America, Asia, and the Middle East.

As the exhibition catalogue preface alerts readers: ‘This exhibition has been modified from its original version. It has been formatted to include others.’ These ‘other’ works were displayed against backdrops of enlarged black and white photographs from 1966, together with a scale-model replica of the original show. Yet the danger is that even if you reshuffle the deck of exhibition histories – Rasheed Araeen instead of Robert Morris, Lygia Clark not Phillip King – the cards inadvertently fall in the same pattern. Hoffmann’s ‘Other Primary Structures’ recreation arguably ran the risk of reinforcing the dominance of US minimalism as an art-historical category, rather than challenging or complicating it. Despite this, ‘Other Primary Structures’ fruitfully conveys how an exhibition can be reinterpreted. Equally, there are other effects to be gained that are not as didactic, but no less intriguing.

One exhibition that has lived through several versions is the Swiss curator Harald Szeemann’s ‘When Attitudes Become Form (Works – Concepts – Processes – Situations – Information)’ from 1969 at the Bern Kunsthalle. Szeemann described how his highly influential show, which included post-minimalist and conceptual art works, sought to transform the gallery space into a ‘laboratory’. It included many pieces that were made on-site, using the fabric of the Kunsthalle itself, and marked a new approach to curatorial endeavour as an experimental and creative activity in its own right. In 2013, under the curatorship of Germano Celant, the layout of the exhibition was painstakingly translated on to the floor plan of a Venetian Palazzo. The design, modelled with the help of Rem Koolhaas and Thomas Demand, closely corresponded to archival photographs and documentation, and missing works were marked out with dotted lines.

The temporal vertigo achieved by Celant’s 2013 Venice version of ‘When Attitudes Become Form’ was extreme. As many of the pieces had been made from perishable materials, and were in some cases site-specific, there was a deeply uncanny, haunting quality to this attempted salvage, through which present, past and future folded in on one another. The productive temporal instability of such projects, which pitch the viewer into a disorientating blend of nostalgia, loss, and the present continuous tense, moreover, owes much to wider institutional willingness to engage with performance. Having existed on the margins of the mainstream – often intentionally – for several decades, museums have recently adapted themselves to performance art’s demands, courting practitioners such as Marina Abramović and Tino Sehgal to create works for their spaces.

In an essay called ‘After the White Cube’ for the London Review of Books in March this year, the art historian and critic Hal Foster persuasively connects the current embrace of performance to the transformation of museums into machines for experience, providers of entertainment and spectacle. ‘Today,’ he reflects, ‘there’s not enough present to go around: for reasons that are obvious enough in a hyper-mediated age, it is in great demand too, as is anything that feels like presence.’ Admittedly, the recreation of historic exhibitions and displays might partake of this hunt for immediacy, offering ersatz thrills rather than genuine challenge. Yet it is also true that many recreations, rehangs and re-enactments think about the issue of reproduction and the relay of ideas between different points in history.

Yard is an instructive example: Kaprow was a pioneer of performance art, who during the 1990s arranged for multiple recreations of his works at institutions from the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, to the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven. Kaprow was, however, adamant that these were different pieces from the originals: they were recreations rather than repetitions. For Kaprow, each time a work was restaged, it acquired and shed implications and associations, resulting in a living archive that was open to change and contestation.

‘When Attitudes Become Form’ has similarly provided a springboard for subsequent looser versions at the CCA Wattis Institute in San Francisco during 2012 (also curated by Hoffmann) and the Whitechapel Art Gallery in 2000, which invoked elements of the show according to the spirit rather than the letter. These are perhaps more accurately described as departures rather than returns, acknowledging Szeemann’s impact but seeking to complicate his dominance of exhibition histories since the 1960s.

An exhibition ‘Five Issues of Studio International’ at Raven Row (until 3 May 2015), curated by Jo Melvin, offers another suggestive take on recreation. By returning to selected issues of the UK-based magazine, which dealt specifically with sculpture, Melvin’s absorbing exhibition doesn’t rehang a specific show, but rather reactivates a network of thought from the 1960s and 1970s and gives it a physical, but deliberately provisional, form.

As Jens Hoffmann observes in his introduction to the ‘Other Primary Structures’ catalogue: ‘When it comes to exhibitions…we are only beginning to entertain the question of how they might be restaged and experienced anew, decades and continents removed from their original presentation.’ Recreating historical displays can offer valuable opportunities to explore what we think of as established art histories from new and unexpected perspectives. At the same time, curators and institutions need to consider carefully which exhibitions and displays they choose to reproduce. ‘When Attitudes Become Form’, for example, has been exhaustively studied and recreated. Curators, historians, artists and critics must think carefully about the compulsion to return, and travel along less well-trodden historical paths, while continuing to re-examine significant shows.

Catherine Spencer is a lecturer in modern and contemporary art at the University of St Andrews.

Click here to buy the latest issue of Apollo

The Apollo Inquiry

Learning Lessons | The radical potential of museum education

Wall Flowers | Women in historical art collections

Right or wrong? | Is it time to rethink copyright legislation?

Attention Seekers | Do touchscreens, apps and the like enrich visitor experience?

The Asian Biennial Boom | How have unconventional spaces shaped artists’ practices in the region?

Art law and attribution | Do art historians and other art authenticators need greater legal protection?

Hard times for the UK’s regional museums? | How have recent funding cuts affected museums?

Making it New: the trend for recreating exhibitions

Picture by Gabriel Szabo/Guzelian

Visitors experience the UK’s first presentation of Allan Kaprow’s seminal work YARD (1961). Featuring 3,000 tyres, Allan Kaprow: YARD 1961/2014 opens at The Hepworth Wakefield’s new contemporary art space - The Calder, on Friday 4 July until 31 August. www.hepworthwakefield.org

American artist Allan Kaprow was the inventor of ‘Happenings’ or ‘Environments’, a term popularised in the 1960s for site-specific installations and participant-led activities. Kaprow’s ground-breaking rejection of formal aesthetics his “un-art” approach revolutionised art and paved the way for performance art and influenced successive artists including: Franz West, Claes Oldenburg and Marina Abramović.

Interventions by artists, musicians and dancers will take place throughout the duration of the show: Siobhan Davies Dance, Brazilian artist Rivane Neuenschwander, South Korean artist Koo Jeong-A, British artist and musical collaborators David Toop and Rie Nakajima.

Dispersed in no particular order, Kaprow tossed the tyres around, to encourage visitors to walk on, climb, rearrange and interact with them.

Share

From the May issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here

Why do museums recreate landmark exhibitions, installations and performances, and what can we learn from these restagings?

Last year, the Hepworth Wakefield filled its recently opened project space, situated upriver from David Chipperfield’s iconic building in a reclaimed warehouse, with a mass of car tyres. The sea of rubber was an eloquent statement on post-industrial malaise in its own right, but the exhibit came with a long history as well. Yard, by the US artist Allan Kaprow, was first displayed in 1961 at the Martha Jackson Gallery in New York. Its Hepworth appearance was one of many reinventions of the work over the years: an example of how institutions have now become open to the recreation of past installations and exhibitions.

The influences fuelling the current appetite for reinstalling, re-exhibiting, and restaging are complicated. They range from pedagogic and archival ambitions, through to the transformation of art museums into venues for mediums such as film, video, performance art and dance. While ‘repetition’ implies faithfulness to an original, ‘recreation’ and ‘reinvention’ hint at the inevitable, even desirable changes that creep in with each iteration. At their most productive, such returns can challenge our conventional definition of a ‘historic’ exhibition, and prompt us to create alternative histories.

Allan Kaprow installing the first version of ‘Yard’, in the sculpture garden of Martha Jackson Gallery in New York, 1961. Courtesy Allan Kaprow estate and Hauser & Wirth. Photo © Ken Heyman

Tate’s recent exhibition programme has contained several notable instances of recreation – and its educational value. Tate Modern’s 2014 Kazimir Malevich show partially recreated a section of ‘The Last Exhibition of Futurist Painting 0.10 (Zero-Ten)’, held in Petrograd during 1915. Guided by the one surviving photograph of this exhibition, with which Malevich unveiled his vision of Suprematist art, the curators positioned the 1929 version of Malevich’s Black Square in the upper corner of one room. With this gesture, Malevich claimed the space normally housing a Russian icon for his painting. Although Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall is no stranger to experimental installations, the Malevich rehang underlined how subtle alterations in established methods of display can still retain a radical charge decades after their original occurrence.

Overlapping with the Malevich show in London, Tate Liverpool’s ‘Mondrian and his Studios’ followed the recreation impulse even further by structuring its display around a full-scale replica of Piet Mondrian’s Paris workspace. While in the wrong hands this might have produced a recherché period room, the effect was a vivid realisation of the architectonic aspirations that Mondrian had for his painting, and for the Neo-Plasticist movement. Through recreation, ‘Mondrian and his Studios’ could convey Mondrian’s understanding of abstraction as a vital part of everyday life, rather than a rarefied exercise in formalism.

Installation view showing the recreation of Piet Mondrian’s (1872–1944) Paris studio at Tate Liverpool, 2014. Image courtesy Tate Liverpool. Photo: Roger Sinek

On walking into Tate Modern’s 2014 Richard Hamilton retrospective, audiences were plunged into a meticulously curated rehang of Hamilton’s 1951 exhibition ‘Growth and Form’, which was organised to coincide with the Festival of Britain. As they moved further into the Tate show, visitors found themselves in a resurrection of the iconic ‘fun house’ installation Hamilton collaborated on for the 1956 ‘This is Tomorrow’ exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery. Across the Thames, the Institute of Contemporary Arts extended the retrospective by redisplaying Hamilton and Victor Pasmore’s 1957 installation, An Exhibit.

By going to all this trouble, rather than simply providing archival photographs of the earlier exhibitions in a vitrine, the curators showed how Hamilton’s experiments directly contributed to innovations in exhibition design, and allowed audiences to trace his thought-processes across several aspects of his work. Hamilton’s career testifies to the importance of installation as an artistic practice, and its effect on the presentation and reception of art in the latter part of the 20th century. Pieces like An Exhibit and Yard are pre-programmed for being transposed to other places: they are responsive to their sites, but not inherently site-specific. This flexibility, combined with the increasingly blurred roles of artist and curator, has been central to the growing enthusiasm for revisiting whole exhibitions.

Such recreations are, often by default, institutional projects. They demand dedicated archival sleuthing, agreement from artists’ estates and copyright holders, and levels of technical labour that only large organisations can provide. The scholarly endeavour involved is frequently exemplary. The process offers a dynamically different way of conducting research, and of bringing it to a much wider audience than an academic publication could.

A key precedent in this respect is the 1991 exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, “‘Degenerate Art”: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany’. Its curator, Stephanie Barron, staged a room-for-room rehang of the infamous 1937 exhibition ‘Entartete Kunst’ (Degenerate Art)’, organised by the National Socialist Party in Munich as a condemnation of modern art, exploring how the display was used to construct an ideology of racial ‘purity’ and its propagandist effects. In cases such as this, the rationale for reinvestigation seems clear, but it nonetheless remains vital to engage with questions about the reasons and criteria governing such returns, as it is here that their most interesting and provocative implications can be found.

Some projects wear their revisionist criteria on their sleeves. During 2014, the Jewish Museum in New York staged ‘Other Primary Structures’, a two-part update of their 1966 exhibition ‘Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculptors’, which established what would become the canon of minimalist sculpture. Curated by Jens Hoffmann, ‘Other Primary Structures’ sought to rewrite the history of this moment by expanding the original 1966 show beyond its myopic Anglo-American focus, instead featuring sculptures made during the same period by artists from Latin America, Asia, and the Middle East.

As the exhibition catalogue preface alerts readers: ‘This exhibition has been modified from its original version. It has been formatted to include others.’ These ‘other’ works were displayed against backdrops of enlarged black and white photographs from 1966, together with a scale-model replica of the original show. Yet the danger is that even if you reshuffle the deck of exhibition histories – Rasheed Araeen instead of Robert Morris, Lygia Clark not Phillip King – the cards inadvertently fall in the same pattern. Hoffmann’s ‘Other Primary Structures’ recreation arguably ran the risk of reinforcing the dominance of US minimalism as an art-historical category, rather than challenging or complicating it. Despite this, ‘Other Primary Structures’ fruitfully conveys how an exhibition can be reinterpreted. Equally, there are other effects to be gained that are not as didactic, but no less intriguing.

One exhibition that has lived through several versions is the Swiss curator Harald Szeemann’s ‘When Attitudes Become Form (Works – Concepts – Processes – Situations – Information)’ from 1969 at the Bern Kunsthalle. Szeemann described how his highly influential show, which included post-minimalist and conceptual art works, sought to transform the gallery space into a ‘laboratory’. It included many pieces that were made on-site, using the fabric of the Kunsthalle itself, and marked a new approach to curatorial endeavour as an experimental and creative activity in its own right. In 2013, under the curatorship of Germano Celant, the layout of the exhibition was painstakingly translated on to the floor plan of a Venetian Palazzo. The design, modelled with the help of Rem Koolhaas and Thomas Demand, closely corresponded to archival photographs and documentation, and missing works were marked out with dotted lines.

The temporal vertigo achieved by Celant’s 2013 Venice version of ‘When Attitudes Become Form’ was extreme. As many of the pieces had been made from perishable materials, and were in some cases site-specific, there was a deeply uncanny, haunting quality to this attempted salvage, through which present, past and future folded in on one another. The productive temporal instability of such projects, which pitch the viewer into a disorientating blend of nostalgia, loss, and the present continuous tense, moreover, owes much to wider institutional willingness to engage with performance. Having existed on the margins of the mainstream – often intentionally – for several decades, museums have recently adapted themselves to performance art’s demands, courting practitioners such as Marina Abramović and Tino Sehgal to create works for their spaces.

In an essay called ‘After the White Cube’ for the London Review of Books in March this year, the art historian and critic Hal Foster persuasively connects the current embrace of performance to the transformation of museums into machines for experience, providers of entertainment and spectacle. ‘Today,’ he reflects, ‘there’s not enough present to go around: for reasons that are obvious enough in a hyper-mediated age, it is in great demand too, as is anything that feels like presence.’ Admittedly, the recreation of historic exhibitions and displays might partake of this hunt for immediacy, offering ersatz thrills rather than genuine challenge. Yet it is also true that many recreations, rehangs and re-enactments think about the issue of reproduction and the relay of ideas between different points in history.

Yard is an instructive example: Kaprow was a pioneer of performance art, who during the 1990s arranged for multiple recreations of his works at institutions from the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, to the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven. Kaprow was, however, adamant that these were different pieces from the originals: they were recreations rather than repetitions. For Kaprow, each time a work was restaged, it acquired and shed implications and associations, resulting in a living archive that was open to change and contestation.

‘When Attitudes Become Form’ has similarly provided a springboard for subsequent looser versions at the CCA Wattis Institute in San Francisco during 2012 (also curated by Hoffmann) and the Whitechapel Art Gallery in 2000, which invoked elements of the show according to the spirit rather than the letter. These are perhaps more accurately described as departures rather than returns, acknowledging Szeemann’s impact but seeking to complicate his dominance of exhibition histories since the 1960s.

An exhibition ‘Five Issues of Studio International’ at Raven Row (until 3 May 2015), curated by Jo Melvin, offers another suggestive take on recreation. By returning to selected issues of the UK-based magazine, which dealt specifically with sculpture, Melvin’s absorbing exhibition doesn’t rehang a specific show, but rather reactivates a network of thought from the 1960s and 1970s and gives it a physical, but deliberately provisional, form.

As Jens Hoffmann observes in his introduction to the ‘Other Primary Structures’ catalogue: ‘When it comes to exhibitions…we are only beginning to entertain the question of how they might be restaged and experienced anew, decades and continents removed from their original presentation.’ Recreating historical displays can offer valuable opportunities to explore what we think of as established art histories from new and unexpected perspectives. At the same time, curators and institutions need to consider carefully which exhibitions and displays they choose to reproduce. ‘When Attitudes Become Form’, for example, has been exhaustively studied and recreated. Curators, historians, artists and critics must think carefully about the compulsion to return, and travel along less well-trodden historical paths, while continuing to re-examine significant shows.

Catherine Spencer is a lecturer in modern and contemporary art at the University of St Andrews.

Click here to buy the latest issue of Apollo

The Apollo Inquiry

Learning Lessons | The radical potential of museum education

Wall Flowers | Women in historical art collections

Right or wrong? | Is it time to rethink copyright legislation?

Attention Seekers | Do touchscreens, apps and the like enrich visitor experience?

The Asian Biennial Boom | How have unconventional spaces shaped artists’ practices in the region?

Art law and attribution | Do art historians and other art authenticators need greater legal protection?

Hard times for the UK’s regional museums? | How have recent funding cuts affected museums?

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

Share

Recommended for you

Women artists get a raw deal in historical collections. Will that ever change?

The imbalance seems historically ingrained. But surely museums could do more to explain it

Affordable Art

A new 50p piece, designed by Tom Phillips to celebrate the centenary of Benjamin Britten’s birth, attempts to ‘set the wild echoes flying’

Museums have finally woken up to the potential of 3D printing

3D prints are the new plaster casts