A round-up of the week’s reviews and interviews…

The Quiet Biennale: the Eighth Berlin Biennale is deliberately introspective (Stephen Truax)

The Quiet Biennale: the Eighth Berlin Biennale is deliberately introspective (Stephen Truax)

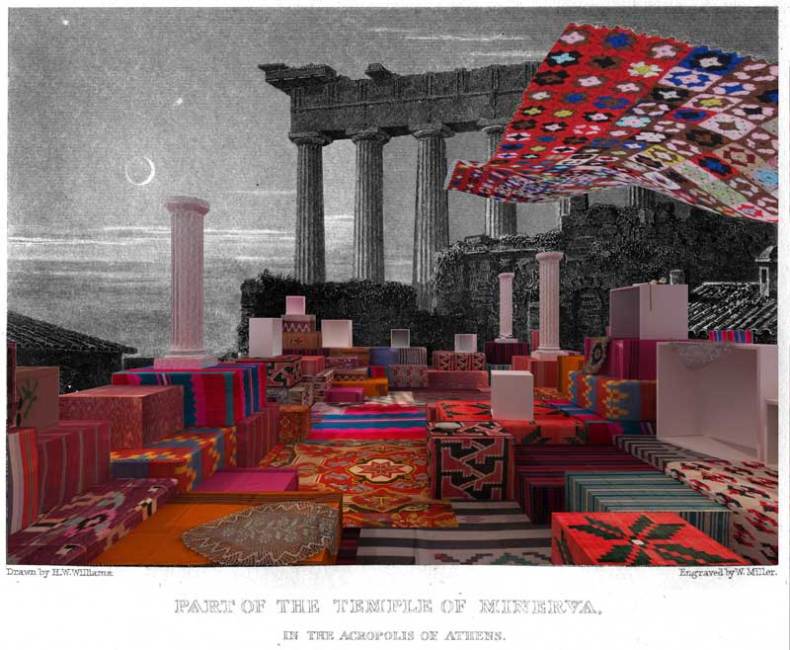

Juan A. Gaitán’s exhibition is an intentional letdown. Extremely restrained, and focused on groups of small drawings and studies, it adopts the most traditional museological presentation and language, and presents works that are prepositions rather than statements. Without a guide, this Biennale can be boring. Yet it is nonetheless politically charged. The three exhibitions that comprise this year’s event are remarkable in their introspective silence, which Gaitán sees as a refusal of the totalitarian ideals enabled by the scale, spectacle and deliberate exoticism of the typical biennale format.

Shells, rocks and follies: the Serpentine Pavilion 2014 responds well to its location (Zofia Trafas)

The annual summer Pavilion is an eagerly awaited temporary addition to the landscape of London’s Hyde Park – and it’s exciting when the structure’s design forms a particularly strong bond with its surroundings. Not all previous pavilions have been successful in this respect, and some fell into the mode of stiff and self-contained iconic miniature-buildings. However Radić’s design succeeds with a fluid and open-ended structure that interacts with its natural context, while also offering an interesting nod to the architectural tradition of the garden folly.

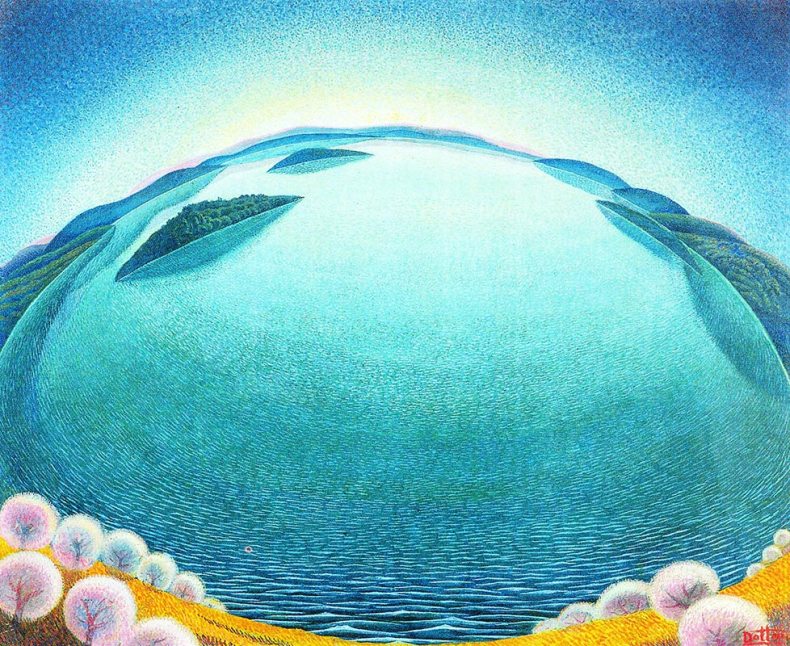

‘Gerardo Dottori: The Futurist View’ at the Estorick Collection (Jon Day)

One of the main ideological sources of aeropainting – and one reason it was so popular with fascists – was aerial combat…But unlike the aeropaintings of Guglielmo Sansoni and Tullio Crali, which glorified the martial dynamism of the aeroplane, locating the viewer in the cockpits of strafing bombers, Dottori’s paintings show bucolic, neon-fringe utopias, glinting with water: fish-eyed landscapes suggesting the curvature of the earth and the boundlessness of flight.

‘Giulio Paolini: To Be or Not to Be’ at the Whitechapel Gallery (Rosalind McKever)

Paolini, who came to prominence as part of Italy’s arte povera generation, has long been a major figure in conceptual art, but has rarely been exhibited in the UK. The exhibition offers a long overdue presentation of an artist whose questioning of authorship and authenticity maintains its relevance in the digital age.

Salk Institute in La Jolla, California (1959–65), Louis Kahn. The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania. Photo: John Nicolais

‘Louis Kahn: The Power of Architecture’ at the Design Museum (Otto Saumarez Smith

With their solemnity, evocations of ancient construction, Euclidean geometry and heavy grandeur, these buildings speak to a core of experience that Kahn is almost alone amongst modernist architects in reaching. They feel mythic.

Gilbert & George photographed in their Fournier Street studio in London, June 2014 (detail) Photo: Kate Peters

Gilbert & George Interview: July/August Apollo (Martin Gayford)

‘We always said that London was the centre of the universe,’ George reflects, ‘that it was the most typical planet Earth place. No one believed us in the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s. Now everyone agrees.’ I remember Gilbert & George saying exactly this, and it did indeed once seem – like much that they proclaim – challengingly paradoxical. And, as with so many of their paradoxes, they pushed it just a little bit further: the epicentre of everything, they seem to imply, is chez G&G.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?