A round-up of the week’s reviews

‘Another Life, Another World’: Paul Nash’s watercolours (Maggie Gray)

Nash’s watercolours from the 1920s and ‘30s breathe easier than his dense wartime sketches, with a lightness of touch that he never achieved (nor, I suspect, attempted) in oils. But they still leave little to chance. Throughout the show, I was struck by the structures that weigh down the artist’s washes: his methodical hatching in pen and pencil, that divides up the page like a tapestry; the ruled edges of his architectural elements; the grids, colour notes and revised outlines sitting visible under thin washes of paint.

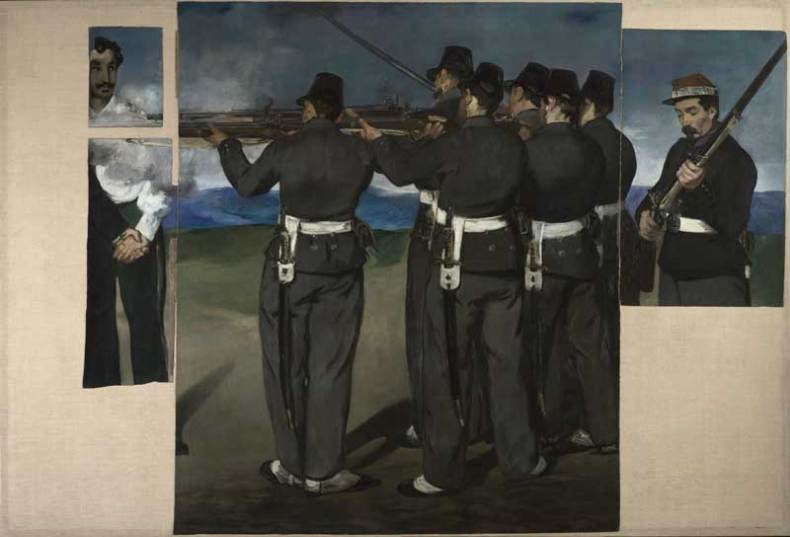

‘Unreliable Evidence’: Manet and contemporary art in the Mead Gallery (Anneka French)

Of Manet’s painting, only the sleeve and fingers of the titular Maximilian can be seen; the work has been sliced and pieced back together, some pieces are lost forever, and the backing is visible. These are perhaps the most intriguing aspects of the work, despite its political subject. Each of these alterations have contributed to its cultural and monetary value, and resonate with the themes of the exhibition: occlusion, editing, back-stories. The problem, though, is that The Execution of Maximilian, in this context, struggles to maintain its own presence alongside the vital and urgent contemporary works.

Picking the picture: Magnum Contact Sheets at C/O Berlin (Lily Le Brun)

Contact sheets are like the first draft, the artist’s sketchbook or a diary. They are normally forbidden territory, and as well as logging movements and decisions, they show surprising details, mistakes, and lucky coincidences. They breathe life into the images, many of which have become victims of their own success. Precisely because of their power, and because they have become so familiar, they have become separated from their original meaning. The exhibition helps to redress this.

‘F for Fibonacci’ by Beatrice Gibson, at Laura Bartlett Gallery, London, 2014. Courtesy Laura Bartlett Gallery

‘Beatrice Gibson, F For Fibonacci’ at Laura Bartlett Gallery (Imelda Barnard)

[Gibson’s] films consistently revolve around fiction, the voice, sound, and the slippery nature of language itself…F for Fibonacci, currently on show at Laura Bartlett Gallery in London’s East End explores many of the same subjects. Literary fiction is once again the film’s departure; this time, it’s William Gaddis’s biting satire, JR. The novel follows an 11-year-old capitalist who creates (with the help of the school’s resident composer) a vast financial empire, mostly from the confines of a phone booth…Gibson’s film…is a disorderly artwork that performs and plays with Gaddis’s text.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?