Materials and meaning came together last week, as art historians, curators and conservators met at the Wallace Collection in London to discuss the works of Joshua Reynolds. The one-day conference was associated with the Wallace’s current exhibition ‘Joshua Reynolds: Experiments in Paint’, which comes out of a four-year research project to investigate the museum’s outstanding collection of his works. Under the theme ‘Challenging Materials: Joshua Reynolds and artistic experiment in the eighteenth century’, papers highlighted how Reynolds’ experimentation with both his materials and his subjects offer a different perspective on the period.

The Strawberry Girl (1772–3), Joshua Reynolds © The Wallace Collection. Photo: The National Gallery, London

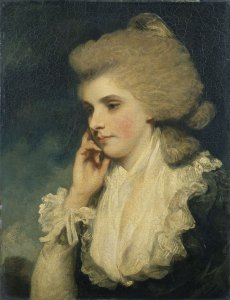

Reynolds is famous for experimenting with his subject matter, moving beyond the conventions of society portraiture to depict social types and characters rather than individuals. Iris Wien approached his well-known Strawberry Girl, in the Wallace Collection, as an example of a modern allegory, in which the girl’s bowed shoulders and humble posture contrast with her direct, limpid gaze, challenging social categories. Thus the decayed surface of the painting only accentuates the sense of consumption and fragility inherent in the portrait.

Reynolds’ history painting was, perhaps, his ultimate experiment. Conservation work on two of his grandest history paintings has shown just how experimental they were in their material as well as intellectual make-up. Papers on Macbeth at Petworth House and The Infant Hercules strangling the Serpents at the Hermitage highlighted how he composed his grand narratives directly on the canvas, without under drawing, sometimes leading to an extraordinary number of visible paint layers. Rica Jones, likewise, discussed how Reynolds experimented with resin among his binding agents in constant search of fabulous paint effects.

Such experiments meant that Reynolds’ works were seen as unstable, however, in their subject matter and reputation, as much as in their materials. John Chu examined the collection of John Sackville, 3rd Duke of Dorset, and argued that his taste for the ‘slowly self-consuming beauty’ of Reynolds’ works was part of elaborate, almost self-destructive, conspicuous consumption. The Duke collected Reynolds’ subject pictures as a social gamble, a high-risk experiment that provided him with cultural capital among London’s beau monde.

What emerged from the conference, was the moral message that materials can also convey. Marcia Pointon discussed Reynolds’ enigmatic portrait of Marie Countess of Schaumburg-Lippe, in which two unfinished sections contrast the sitter’s softly modelled and delicately tinted face with an extraordinary impasto diamond brooch positioned at her breast. The different painting techniques not only allowed Reynolds to experiment, Pointon suggested, but also to consider the social meanings around the layering of skin, jewellery and dress. Mark Aronson suggested there is meaning, likewise, in Reynolds’ reuse of such unfinished canvases. He argued for canvas to be seen as a time-based media, subject to instability and decay (just like Reynolds’ pigments), open to use and re-use in a busy studio, and therefore a constant source of inspiration.

Frances, Countess of Lincoln (1781–2), Joshua Reynolds © The Wallace Collection, Photo: The National Gallery, London

Lastly, the tension between art and nature was brought into focus by consideration of Reynolds’ legacy in the age of industry. William Hilton and Henry Perronet Briggs provided Cora Gilroy-Ware and Martin Myrone, respectively, with a means to consider 19th-century artistic training and practice. Both Reynolds’ compositions and his experimental materials provided a means to confront the power of industrialisation, but they were also part of how an artist taught himself to paint in the period, and therefore a tool for social mobility.

This style of art history consciously champions sensitivity to the materials of fine art. In the breaks between papers, I found myself increasingly aware of the painted surface of Reynolds’ portraits in the Wallace’s exhibition: the technical artifice used to conjure the sitter behind the paint. If Reynolds’ reputation has disintegrated along with his experimental canvases, the moral of the conference was that attention to the details of one will restore the other.

‘Joshua Reynolds: Experiments in Paint’ is at the Wallace Collection, London, until 7 June.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?