Around a year ago, when the government of Ukraine decided to codify the ‘Leninopad’ (‘Leninfall’) that had overtaken much of the country into law, many Western journalists were amazed by the sheer quantity of monuments to a regime that they considered to be uncomplicatedly evil. On the streets of Donetsk, Lugansk, Odessa, Dnepropetrovsk, were statues of Felix Dzerzhinsky, the founder of the Cheka, the forerunner to the KGB, held responsible for a brutal ‘Red Terror’ during the Russian Civil War of 1918–21. There were statues of the likes of Kliment Voroshilov, the general who was for decades Stalin’s right-hand-man, and Mikhail Kalinin, Stalin’s puppet president. Entire cities and counties were named after people such as Sergei Kirov, the chief of the city of Leningrad, whose assassination in 1934 (possibly on Stalin’s orders) sparked the Great Terror; and the fourth-largest city was named after Grigory Petrovsky, a Ukrainian Bolshevik. And most of all, there was Lenin after Lenin after Lenin, even after many of them in Central Ukraine had been pulled down by protesters. A popular wave of iconoclasm became formal law in a ‘De-Communisation’ decree, which also mandated the building of statues to Ukrainian national heroes. Aside from the occasional sceptical comment, this was largely met with applause in the international media, and the more comic examples – a statue of Lenin turned into Darth Vader – went viral. The mockery, desecration, and toppling of statues was to be celebrated, as an example of a country shaking off its dark, totalitarian past and marching towards an optimistic, open, European future.

Statue of Lenin in Kharkiv, erected in 1964 and removed in 2014. Photo: Owen Hatherley

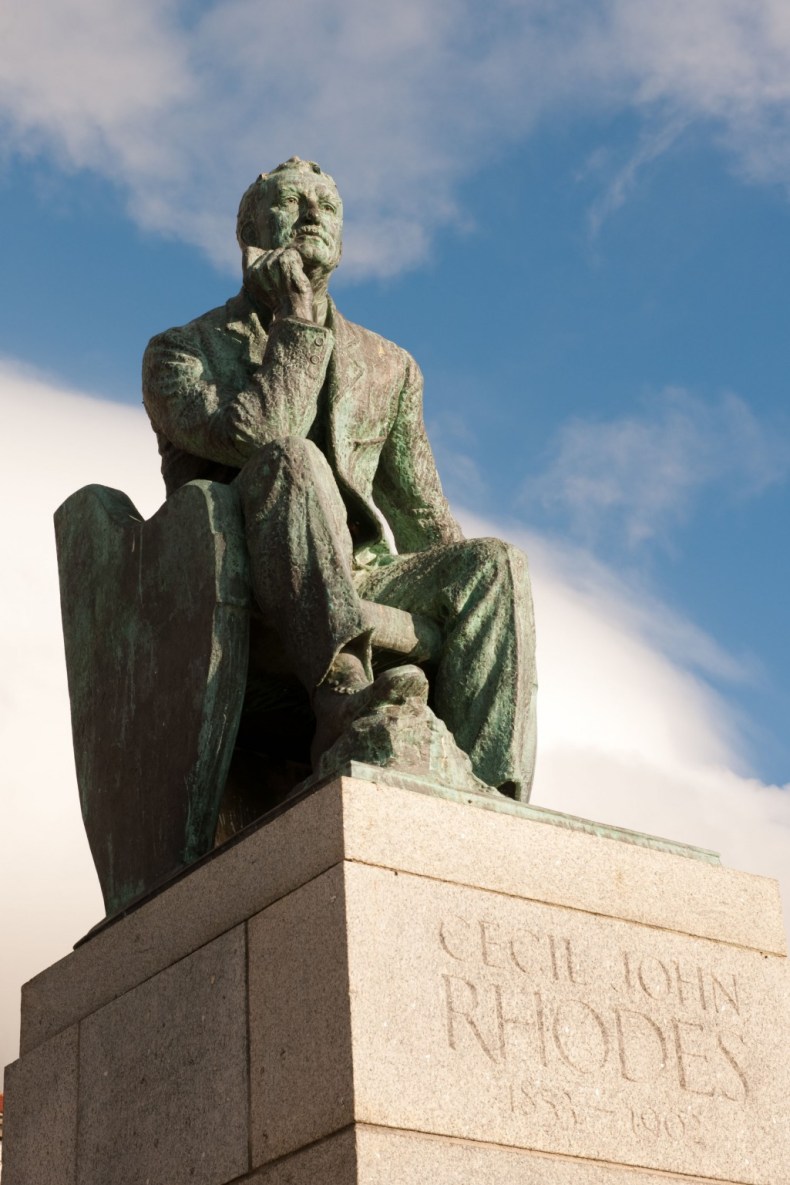

How strikingly different was the reaction the same year to the ‘Rhodes Must Fall’ campaign. Beginning in Cape Town and eventually spreading to Oxford, this was much smaller and more localised than the mass Leninopad in Ukraine, and it involved more public debate. It has focused on, first, a bronze statue of Cecil Rhodes at the University of Cape Town, unveiled in 1934, which became the focus of a student campaign, usefully summarised in a hashtag: #RhodesMustFall. It escalated to vandalism of the Rhodes Memorial, where a bust of the imperialist, an allegorical figure representing ‘physical energy’, and eight bronze lions, form part of a neoclassical temple on Devil’s Peak, a hill overlooking the city. The University of Cape Town statue was eventually removed and the campaign was picked up at the other side of the former imperial system – not the colony, but the centre.

Statue of Cecil Rhodes on the façade of Oriel College, Oxford on the High Street, built in 1911.

Oxford’s Oriel College was given two per cent of Rhodes’ vast fortune, which came to £100,000, and Oriel College’s newly designed frontage on to The High, paid for with the money, acquired a statue of Rhodes in a niche above its ceremonial gateway. This is the focus for a campaign drawing attention to Rhodes’ role in the expansion of the British Empire across southern Africa, which involved mass murder, racial laws, openly expressed white supremacy, and plunder on an epic scale.

However, commentators were largely horrified. This was the erasure of history, a thuggish anachronistic iconoclasm, driven by people who enjoy the privileges enabled by Rhodes himself and the scholarships his estate administers; in short, as the novelist Howard Jacobson put it, this was the ‘new Cultural Revolution’. There weren’t, to my knowledge, any commentators condemning equally Leninopad and #RhodesMustFall, which is curious indeed. In many of these cases, the statues are oddly similar – quasi-architectural, placed on specially designed classical pedestals and pavilions. With a few tweaks and some gesturing workers, the Rhodes Memorial in Devil’s Peak could be a Soviet monument: centralised, authoritarian, utterly pompous. Similarly, that Physical Energy figure on horseback – a casting of which stands in Kensington Gardens, dedicated to Rhodes – looks not unlike the statue of Voroshilov on his horse in Lugansk.

Equestrian statue of Kliment Voroshilov in his birthplace of Lugansk, Ukraine

The first to demand the removal of the Rhodes statue in Cape Town University, in the 1950s, were Afrikaner students, angered at this symbolic reminder of the aggressor in the Boer War, when Britain pioneered the concentration camp, interning in improvised, insanitary outdoor prisons thousands of Boers (also, thousands of black Africans, though this wasn’t at the forefront of the Afrikaners’ campaign). In Ukraine, the very fact that there were still so many statues of Lenin and lesser Bolsheviks all over the centre, east and south of the country (the west got rid of its Lenins in the early 1990s) was seen as evidence that it hadn’t fully ‘moved on’, that the ghosts of the past had not been properly exorcised, and that in some way, the statues’ continued presence at the centre of various large public squares was evidence that Communism – and a ‘Soviet mentality’ – persisted in some form.

The fact that #RhodesMustFall took place 20 years after the end of Apartheid was not granted the same clemency, though an equally plausible argument could have been made: that the continued presence of these statues and monuments in public space represented a ‘colonial mentality’, showing that values had not really changed (despite the massive changes that had clearly taken place). In both cases, some journalists tried to make a case for their retention on historical grounds. Some pointed out that Lenin actually encouraged a ‘Ukrainisation’ campaign in the 1920s, which saw the promotion of the native language and literature on a greater scale than at any time until the 1990s, so using him as a symbol of Russification and an anti-Putin gesture was rather anachronistic. More unconvincingly, some pointed to the fact that Rhodes was not personally racist – he had black friends! – as evidence that the violent occupation of around a quarter of a continent was irrelevant.

Rhodes Memorial on Devil’s Peak, Cape Town, designed by Francis Macey and Herbert Baker in 1906 and completed in 1912. Photo: © Pete Titmuss/Alamy Stock Photo

The argument that the campaign erases history is much more peculiar. What #RhodesMustFall actually does is draw attention to history which is usually ignored – how many are aware of the Rhodes statue in its niche as they walk along the High Street, and how many even know who Rhodes scholarships are named after? Rhodes is too often vaguely remembered as a charismatic rogue, if he is remembered at all in the country in which he was born. In the countries (Zambia and Zimbabwe) formed from the state he created (Rhodesia), the matter is rather different. Rhodes’ credo, expressed in his Will, is exceptionally straightforward. It calls for ‘the establishment, promotion and development of a Secret Society, the true aim and object whereof shall be for the extension of British rule throughout the world, the perfecting of a system of emigration from the United Kingdom, and of colonisation by British subjects of all lands where the means of livelihood are attainable by energy, labour and enterprise, and especially the occupation by British settlers of the entire Continent of Africa, the Holy Land, the Valley of the Euphrates, the Islands of Cyprus and Candia, the whole of South America, the Islands of the Pacific not heretofore possessed by Great Britain, the whole of the Malay Archipelago, the seaboard of China and Japan, the ultimate recovery of the United States of America as an integral part of the British Empire…’

Statue of Cecil Rhodes at the University of Cape Town, erected in 1934 and removed in 2015. Photo: © Ariadne Van Zandbergen/Alamy Stock Photo

Much of this terrifying programme was achieved in the early 20th century, as mandates in the Middle East accompanied the African Empire that Rhodes had carved out through ferocious violence and wholesale pillage. Before they too started to destroy statues and monuments to the pagan and Christian empires that preceded the first Caliphate, ISIS drew attention to this, decreeing the ‘end of Sykes-Picot’, the agreement between Britain and France to carve up the Ottoman Empire between them. This secret agreement was made public in 1918, by the new revolutionary Russian government headed by none other than V.I. Lenin. So much for the idea that Rhodes and his ilk were just products of their time, opposed by nobody.

A useful counterfactual here would place a journalist from some future postcolonial world in which the centre of the British Empire is as dilapidated as the old USSR, to wander round its devastated capital, littered with the remnants of an old ideology. What will he find, walking round its central squares? Four plinths in Trafalgar Square: one occupied by a king; one empty, but what else? Well, one plinth is occupied by Charles James Napier, who, a quick google could have told our journalist from the future, conquered Sindh. Next to him they’d find Henry Havelock, who distinguished himself in counter-insurgency and terror during the suppression of the Indian revolt of 1857, in which the populations of entire villages were killed, and those murdered often humiliated beforehand – by being, for example, sewn into pig skins (as recorded by W.H. Russell of The Times). Busts nearby featured the Earls Beatty and Jellicoe, admirals who helped suppress another local revolt, the Boxer Rebellion in China. Or they could go to Bristol, where they’d find memorials to and concert halls named after the slave trader Edward Colston, or they could go to Glasgow, where at George Square, they’d find a statue of Colin Campbell, Baron Clyde, who served in the First Opium War (among other campaigns), not a particularly glorious moment in British history. This leads to the question many have asked – if Rhodes falls, how do we know when to stop?

Here, unexpectedly, the Ukrainian example proves useful. In the mid 2000s, before the official Leninopad, a memorial in the shape of a tall, minaret-like tower was erected on a hill above the Dnieper, in Kiev, to the victims of the Great Famine of 1933, in which millions starved while grain continued to be exported, as they did in British-controlled Bengal a decade later. This memorial is a short distance away from the Victory Obelisk to the Soviet triumph in the Great Patriotic War, when it made such a great contribution to the defeat of Nazi Germany. The two are together, now inextricable. Perhaps something similar can occur to the monuments in Britain and its Empire. Memorials to the British Empire’s role in defeating Fascism could be combined with monuments to the millions who starved in Bengal in 1943–44. The Rhodes, Havelocks, Napiers, Campbells, and Colstons would be accompanied by plaques and counter-monuments explaining more fully what these figures did, and how it still warps the relationship between the West, and what the historian and enthusiastic imperialist Niall Ferguson calls ‘the rest’.

From the February issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.

Rewriting the past: must Rhodes fall?

Statue of Cecil Rhodes at the University of Cape Town, erected in 1934 and removed in 2015 Photo: © Ariadne Van Zandbergen/Alamy Stock Photo

Share

Around a year ago, when the government of Ukraine decided to codify the ‘Leninopad’ (‘Leninfall’) that had overtaken much of the country into law, many Western journalists were amazed by the sheer quantity of monuments to a regime that they considered to be uncomplicatedly evil. On the streets of Donetsk, Lugansk, Odessa, Dnepropetrovsk, were statues of Felix Dzerzhinsky, the founder of the Cheka, the forerunner to the KGB, held responsible for a brutal ‘Red Terror’ during the Russian Civil War of 1918–21. There were statues of the likes of Kliment Voroshilov, the general who was for decades Stalin’s right-hand-man, and Mikhail Kalinin, Stalin’s puppet president. Entire cities and counties were named after people such as Sergei Kirov, the chief of the city of Leningrad, whose assassination in 1934 (possibly on Stalin’s orders) sparked the Great Terror; and the fourth-largest city was named after Grigory Petrovsky, a Ukrainian Bolshevik. And most of all, there was Lenin after Lenin after Lenin, even after many of them in Central Ukraine had been pulled down by protesters. A popular wave of iconoclasm became formal law in a ‘De-Communisation’ decree, which also mandated the building of statues to Ukrainian national heroes. Aside from the occasional sceptical comment, this was largely met with applause in the international media, and the more comic examples – a statue of Lenin turned into Darth Vader – went viral. The mockery, desecration, and toppling of statues was to be celebrated, as an example of a country shaking off its dark, totalitarian past and marching towards an optimistic, open, European future.

Statue of Lenin in Kharkiv, erected in 1964 and removed in 2014. Photo: Owen Hatherley

How strikingly different was the reaction the same year to the ‘Rhodes Must Fall’ campaign. Beginning in Cape Town and eventually spreading to Oxford, this was much smaller and more localised than the mass Leninopad in Ukraine, and it involved more public debate. It has focused on, first, a bronze statue of Cecil Rhodes at the University of Cape Town, unveiled in 1934, which became the focus of a student campaign, usefully summarised in a hashtag: #RhodesMustFall. It escalated to vandalism of the Rhodes Memorial, where a bust of the imperialist, an allegorical figure representing ‘physical energy’, and eight bronze lions, form part of a neoclassical temple on Devil’s Peak, a hill overlooking the city. The University of Cape Town statue was eventually removed and the campaign was picked up at the other side of the former imperial system – not the colony, but the centre.

Statue of Cecil Rhodes on the façade of Oriel College, Oxford on the High Street, built in 1911.

Oxford’s Oriel College was given two per cent of Rhodes’ vast fortune, which came to £100,000, and Oriel College’s newly designed frontage on to The High, paid for with the money, acquired a statue of Rhodes in a niche above its ceremonial gateway. This is the focus for a campaign drawing attention to Rhodes’ role in the expansion of the British Empire across southern Africa, which involved mass murder, racial laws, openly expressed white supremacy, and plunder on an epic scale.

However, commentators were largely horrified. This was the erasure of history, a thuggish anachronistic iconoclasm, driven by people who enjoy the privileges enabled by Rhodes himself and the scholarships his estate administers; in short, as the novelist Howard Jacobson put it, this was the ‘new Cultural Revolution’. There weren’t, to my knowledge, any commentators condemning equally Leninopad and #RhodesMustFall, which is curious indeed. In many of these cases, the statues are oddly similar – quasi-architectural, placed on specially designed classical pedestals and pavilions. With a few tweaks and some gesturing workers, the Rhodes Memorial in Devil’s Peak could be a Soviet monument: centralised, authoritarian, utterly pompous. Similarly, that Physical Energy figure on horseback – a casting of which stands in Kensington Gardens, dedicated to Rhodes – looks not unlike the statue of Voroshilov on his horse in Lugansk.

Equestrian statue of Kliment Voroshilov in his birthplace of Lugansk, Ukraine

The first to demand the removal of the Rhodes statue in Cape Town University, in the 1950s, were Afrikaner students, angered at this symbolic reminder of the aggressor in the Boer War, when Britain pioneered the concentration camp, interning in improvised, insanitary outdoor prisons thousands of Boers (also, thousands of black Africans, though this wasn’t at the forefront of the Afrikaners’ campaign). In Ukraine, the very fact that there were still so many statues of Lenin and lesser Bolsheviks all over the centre, east and south of the country (the west got rid of its Lenins in the early 1990s) was seen as evidence that it hadn’t fully ‘moved on’, that the ghosts of the past had not been properly exorcised, and that in some way, the statues’ continued presence at the centre of various large public squares was evidence that Communism – and a ‘Soviet mentality’ – persisted in some form.

The fact that #RhodesMustFall took place 20 years after the end of Apartheid was not granted the same clemency, though an equally plausible argument could have been made: that the continued presence of these statues and monuments in public space represented a ‘colonial mentality’, showing that values had not really changed (despite the massive changes that had clearly taken place). In both cases, some journalists tried to make a case for their retention on historical grounds. Some pointed out that Lenin actually encouraged a ‘Ukrainisation’ campaign in the 1920s, which saw the promotion of the native language and literature on a greater scale than at any time until the 1990s, so using him as a symbol of Russification and an anti-Putin gesture was rather anachronistic. More unconvincingly, some pointed to the fact that Rhodes was not personally racist – he had black friends! – as evidence that the violent occupation of around a quarter of a continent was irrelevant.

Rhodes Memorial on Devil’s Peak, Cape Town, designed by Francis Macey and Herbert Baker in 1906 and completed in 1912. Photo: © Pete Titmuss/Alamy Stock Photo

The argument that the campaign erases history is much more peculiar. What #RhodesMustFall actually does is draw attention to history which is usually ignored – how many are aware of the Rhodes statue in its niche as they walk along the High Street, and how many even know who Rhodes scholarships are named after? Rhodes is too often vaguely remembered as a charismatic rogue, if he is remembered at all in the country in which he was born. In the countries (Zambia and Zimbabwe) formed from the state he created (Rhodesia), the matter is rather different. Rhodes’ credo, expressed in his Will, is exceptionally straightforward. It calls for ‘the establishment, promotion and development of a Secret Society, the true aim and object whereof shall be for the extension of British rule throughout the world, the perfecting of a system of emigration from the United Kingdom, and of colonisation by British subjects of all lands where the means of livelihood are attainable by energy, labour and enterprise, and especially the occupation by British settlers of the entire Continent of Africa, the Holy Land, the Valley of the Euphrates, the Islands of Cyprus and Candia, the whole of South America, the Islands of the Pacific not heretofore possessed by Great Britain, the whole of the Malay Archipelago, the seaboard of China and Japan, the ultimate recovery of the United States of America as an integral part of the British Empire…’

Statue of Cecil Rhodes at the University of Cape Town, erected in 1934 and removed in 2015. Photo: © Ariadne Van Zandbergen/Alamy Stock Photo

Much of this terrifying programme was achieved in the early 20th century, as mandates in the Middle East accompanied the African Empire that Rhodes had carved out through ferocious violence and wholesale pillage. Before they too started to destroy statues and monuments to the pagan and Christian empires that preceded the first Caliphate, ISIS drew attention to this, decreeing the ‘end of Sykes-Picot’, the agreement between Britain and France to carve up the Ottoman Empire between them. This secret agreement was made public in 1918, by the new revolutionary Russian government headed by none other than V.I. Lenin. So much for the idea that Rhodes and his ilk were just products of their time, opposed by nobody.

A useful counterfactual here would place a journalist from some future postcolonial world in which the centre of the British Empire is as dilapidated as the old USSR, to wander round its devastated capital, littered with the remnants of an old ideology. What will he find, walking round its central squares? Four plinths in Trafalgar Square: one occupied by a king; one empty, but what else? Well, one plinth is occupied by Charles James Napier, who, a quick google could have told our journalist from the future, conquered Sindh. Next to him they’d find Henry Havelock, who distinguished himself in counter-insurgency and terror during the suppression of the Indian revolt of 1857, in which the populations of entire villages were killed, and those murdered often humiliated beforehand – by being, for example, sewn into pig skins (as recorded by W.H. Russell of The Times). Busts nearby featured the Earls Beatty and Jellicoe, admirals who helped suppress another local revolt, the Boxer Rebellion in China. Or they could go to Bristol, where they’d find memorials to and concert halls named after the slave trader Edward Colston, or they could go to Glasgow, where at George Square, they’d find a statue of Colin Campbell, Baron Clyde, who served in the First Opium War (among other campaigns), not a particularly glorious moment in British history. This leads to the question many have asked – if Rhodes falls, how do we know when to stop?

Here, unexpectedly, the Ukrainian example proves useful. In the mid 2000s, before the official Leninopad, a memorial in the shape of a tall, minaret-like tower was erected on a hill above the Dnieper, in Kiev, to the victims of the Great Famine of 1933, in which millions starved while grain continued to be exported, as they did in British-controlled Bengal a decade later. This memorial is a short distance away from the Victory Obelisk to the Soviet triumph in the Great Patriotic War, when it made such a great contribution to the defeat of Nazi Germany. The two are together, now inextricable. Perhaps something similar can occur to the monuments in Britain and its Empire. Memorials to the British Empire’s role in defeating Fascism could be combined with monuments to the millions who starved in Bengal in 1943–44. The Rhodes, Havelocks, Napiers, Campbells, and Colstons would be accompanied by plaques and counter-monuments explaining more fully what these figures did, and how it still warps the relationship between the West, and what the historian and enthusiastic imperialist Niall Ferguson calls ‘the rest’.

From the February issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

Share

Recommended for you

Bulgaria must not try to forget its past

Sofia has many important monuments – and they should not be removed or destroyed

Protesting against a historical statue is not just childish – it’s bigoted, too

‘Attitudes change, fortunately, but…things we now find offensive cannot be airbrushed away.’

The long wait for Britain’s Waterloo memorial

It’s taken 200 years for Britain to commemorate the dead