From the September 2015 issue of Apollo: subscribe here

The journey around Sir John Soane’s Museum is a journey through the architect’s life. Now the second floor of No 13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields has returned to its domestic plan after more than a century and a half. And so, the self-portrait that Soane (1753–1837) drew up in his continually evolving group of terrace houses, enshrined in an Act of Parliament as his own house-museum, is almost complete.

The newly revealed and restored private floor, a masterpiece of forensic work by Julian Harrap Architects and the curators at the Soane Museum, is entered through a lobby into the so-called Oratory, richly painted by shafts of light coming through reinstated stained-glass windows off the main stairs. Soane’s first, chosen, visitors to these very personal rooms would have been entirely familiar with his favourite themes and devices. They would have sensed an echo of the basement Monk’s Parlour in the colour-saturated entrance and been reminded of the ground-floor Breakfast Room, where innumerable mirrors are inserted into almost every surface, by the generous convex mirrors hung in both the tiny upstairs Morning Room and on the back of a door in the Model Room. They were Soane’s characteristic way of bursting out of spatial confines.

Eliza Soane’s own room, the Morning Room, contained her personal possessions, both furniture and paintings, with an emphasis on her children. In her widower’s 1834 reorganisation, the hang was adjusted to include his more self-serving choice of large paintings, while it became rather more of an anteroom to the resplendent new Model Room; this was a reconfiguration of Mrs Soane’s Bedchamber – until then untouched, a memorial to Eliza, who had died 20 years before in unhappy circumstances.

With the intricacy of the original layout restored, there is an alternative labyrinthine approach through the book passage (with a deep and ingenious light shaft above), via Soane’s own bedroom (and a plumbed-in bathroom between the two, a remarkably early en suite arrangement), back to the Model Room. There is an emergent, ghostly, sense of family life in this house, but everything is subservient to the presentation of Sir John Soane, architect supreme, offering yet another lens on to his complex mind and prolific practice.

Although Soane was by then over 80 years old, his health and spirits were sufficiently robust for him to offer his own ideas for the rebuilding of the Houses of Parliament. Now was also the moment, he considered, to extend the museum to further celebrate his professional career. Nothing had been more central to his architecture, whether in memory, dreams or reality, than models.

The Model Room, as recreated, faithfully follows a watercolour by C.J. Richardson of around 1834/35. It includes the enclosed loggia with Luigi Mayer’s classical landscapes, its walls painted a rich Pompeian red, while everywhere else on this floor is hung with the original rust-and-cream woodblock wallpaper (the pattern found in an 1830 Cowtan & Sons order book preserved in the V&A).

Over the previous years Soane had moved the models upstairs and downstairs, but the 1834 arrangement showed them off to optimum effect. Yet by 1889 the entire Model Room had been disbanded at the behest of the curator, James Wild, and its contents scattered elsewhere in the museum. Some of the more important examples were lodged in the drawing office.

The project has drawn upon the extraordinary archives in the house. Inventories, bills, diaries, photographs, watercolours and much more have supplied information on almost every detail. Where anything was lacking, the long experience and sharp instincts of the deputy director Helen Dorey and the archivist Susan Palmer supplied missing elements (including the discovery of some of the wallpaper hidden, but in perfect condition, in situ). The extent of the restoration has been signalled clearly: old and new wallpaper coexist, bathroom and other fittings were retrieved from dark corners, stained glass in store was reinstated and, gratifyingly, forgotten material and written sources yielded up their clues.

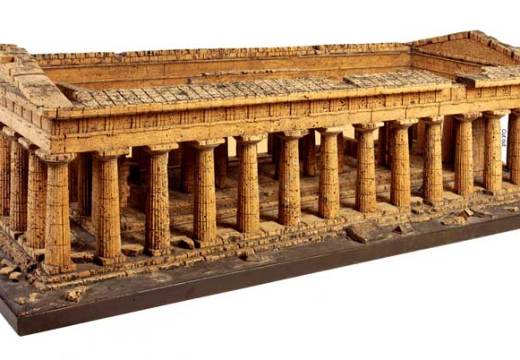

Like his houses, which Soane refigured constantly, the model collection was a work in progress. He bought many of the cork models, which represented the principal sites of classical antiquity, from a major Christie’s auction sale in 1826. Having decided to turn the lugubrious shrine to a long dead woman into the living collection of a working architect, he expanded the collection with Fouquet’s exquisite plaster of Paris pieces, as well as Flaxman’s sculptural models and those of his own office. The materials tell their own story. Cork, itself so like the weathered stone of the Mediterranean; plaster of Paris, pristine, idealised renderings in their glass showcases; wooden models, to be taken apart, studied and altered, as architectural tools, work in progress, equally for the eyes of his office, or for visiting students and clients. There is even a plan model, his own innovation, for the Law Courts, hinged and folded away ingeniously.

The spectacular Model Stand takes up much of the room, its own delicate architecture consisting of tiny columns and multiple levels. Within it, the layout of Pompeii takes pole position, surrounded by key cork models. Around the room, between the windows, set on to shelves, and on the various levels of the stand are many more, in different media, at various scales, and for many purposes. Of Soane’s collection of more than 120 models, 40 are now on display.

The Model Room in particular is an extraordinary re-emergence, well worth the long wait. The opening up of the Soane was initiated by the previous director Tim Knox and continued by his successor, Abraham Thomas, and has been supported by a necessarily enormous raft of funders. If you look out through the upper front windows of No 13, behind the draped figures of the Coade stone caryatids and over the Fields, Soane’s almost limitless ambitions are tangible in this room. Soon after its creation, he was dead and his house/museum became, as intended, solely a museum dedicated to his achievements.

Gillian Darley’s books include John Soane: An Accidental Romantic (Yale) and, most recently, Ian Nairn: Words in Places (Five Leaves), co-written with David McKie.

Sir John Soane’s Private Apartments and the Model Room opened 19 May 2015 at Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam got its rehang right?