Classical art is a heritage of loss. The great majority of the works of art produced in ancient Greece and Rome no longer survive. Paintings have rotted, crumbled or burned. Marble statues were smashed or perished in medieval lime-kilns. As for sculpture in bronze, it has suffered as a result of its intrinsic material value, with statues melted down and recycled throughout the intervening centuries.

Bronze was an important and prestigious material in classical art. Large-scale bronze statuary was extremely difficult to make well but at its best it offered a dynamism and subtlety that is rarely matched in stone. Bronze sculpture starts with the modelling of clay and wax, and contrasts with the unforgiving, reductive process of marble-carving in which one false move with the chisel or an unexpected flaw in the stone can spell disaster. Both marble and bronze statues filled the cities and sanctuaries of the Graeco-Roman world, but bronzes often seem to have been held in special esteem. The modern visitor to a classical site will frequently find the stone bases for lost bronze portrait-statues. They have left their ‘foot-prints’ behind – the cavities where the bronze feet were attached to the pedestal – as if they have just stepped off and walked away.

It is impossible to quantify the scale of what we have lost, but we can get hints. When the 2nd-century travel writer Pausanias visited the great sanctuary of Olympia he noted 69 ancient bronze statues of victors in the Olympic games from the 5th century BC. These would have been high-quality monuments by master-sculptors. Although 13 of their bases have been found, no other traces of the sculptures exist. The Roman encyclopaedist Pliny the Elder, who devoted Book 34 of his Natural History to bronze, reports the claim that there were 3,000 Greek bronzes at Rhodes, and as many at Athens, Olympia and Delphi.

Limestone statue base ‘signed’ by Lysippos, second half of 4th century BC. Archaeolgical site, Corinth

Another telling fact is that our knowledge of celebrated Greek bronze-sculptors, which is mainly derived from later authors such as Pliny, does not correlate with the evidence of archaeology. We are told much about these classical masters: Pheidias who was famous for his colossal gold- and ivory-clad cult-images but also cast bronzes; Polykleitos who theorised about ideal proportions in his treatise called the Canon; Myron who was particularly eulogised for his life-like statues of athletes; and the prolific Lysippos, who worked for Alexander the Great and accomplished a wide range of subjects that included the Apoxyomenos (an athlete scraping oil from his skin) and the intriguingly named ‘Intoxicated Flute-Girl’ (temulenta tibicina). Not a single one of their masterpieces exists today and the closest we get is through tantalising inscriptions on bases. In total, fewer than 30 substantially intact, large-scale bronze statues survive from classical and Hellenistic Greece.

So the classical art historian trying to apprehend the lost inheritance of bronze sculpture has often had to look for proxies. Since the latter half of the 19th century these have been found in marble statues of the Roman period, some of which appear to imitate or even replicate lost bronzes from a much earlier age. It was Adolf Furtwängler (1853–1907) who did most to promote the value of Roman, classicising sculptures in marble as copies of lost works. In his Meisterwerke der griechischen Plastik (1893), Furtwängler advanced a method of Kopienkritik (copy-criticism), which has prevailed in classical art history until recently. Copy-criticism recognised that many Roman sculptures closely and consistently adhered to styles that were first developed in classical Greece centuries before. Moreover, multiple examples of particular figures often existed, reinforcing the impression that a lost prototype lay behind them. Given the Romans’ admiration for the sculptors of classical Greece, it was reasonable to assume that these replicas were copies of antique masterpieces made for the adornment of wealthy houses or public spaces. Some of the most famous classical bronzes such as the Doryphoros (‘Spear Bearer’) by Polykleitos and the Diskobolos (‘Discus Thrower’) by Myron were identified in Roman copies.

Research in the last 20 or 30 years has started to expose a more complex reality behind this traditional picture of Roman copies and lost Greek masterpieces. The Doryphoros of Polykleitos is a good example. The renowned naked bronze, originally designed around the time of the Parthenon (c. 440 BC), became even in antiquity a byword for bodily perfection, and one of its marble copies found in Pompeii has been illustrated in most of the handbooks of Greek art ever written. Another copy, however, from the Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum – itself a rare bronze survival – takes the form of a bust. Why represent the most famous body in art with a copy of its head? And why does the inscription carved on the front record the name of the copyist (‘Apollonios son of Archias, the Athenian’) with no mention of the great Polykleitos? An accumulating body of evidence of this kind suggests that the Roman copyists and their customers may have had altogether different motives than mere emulation. Moreover Vincenzo Franciosi has recently argued, persuasively, that the Doryphoros ‘copies’ have been misidentified all along.

The scarcity of Greek bronze discoveries and a century’s forced reliance on presumed replicas in marble have given the extant bronzes an allure and mystique that has propelled a few of them into popular culture. None are more famous than the two Riace Bronzes, pulled out of the sea off Calabria in 1972. These naked, bearded warriors were made around the middle of the 5th century BC and represent the highest craftsmanship of the period, but their original context is unknown and there has been little consensus about their origin and use. In the desperate pursuit of lost master-sculptors the Riace Bronzes have been inconclusively attributed to the hand of Pheidias, Polykleitos, Alkamenes, Onatas, and Myron… In the 42 years since their emergence these ideal models of Greek masculinity have appeared on Italian stamps, inspired modern artists such as Elisabeth Frink, served as touristic poster-boys, and featured on the cover of a pornographic magazine. In 2014 they were the focus of outrage when images by the photo-grapher Gerald Bruneau emerged in which they were draped with a leopard-skin thong, pink boa, and wedding veil.

The Riace Bronzes are only the most famous of a succession of classical statues or fragments to have been pulled out of the Mediterranean, which suggests that bronze sculpture was often on the move, most probably in cargoes of booty, tradeable antiques, or indeed scrap metal in the Roman period or afterwards. A discovery off the coast can be a godsend to the tourist industry of a small Greek or Italian community, as was the case with the surfacing of the Mazara del Vallo dancing satyr, a powerful, over-lifesize image of Dionysiac revelry, which was found near that Sicilian town in 1998. Here too the aura of the ‘bronze original’ took hold of the imagination of scholars as well as journalists, and the satyr was immediately declared an original masterpiece from the hand of Praxiteles, the famous 4th-century-BC creator of the Aphrodite of Knidos. According to one eminent archaeologist the form of the penis pinned down the authorship conclusively. Others have remained more sceptical.

Dancing Satyr, c. 4th century BC–2nd century AD. Museo del Satiro, Church of Sant’Egidio, Mazara del Vallo

Praxiteles’s skill in bronze made popular headlines again in 2004, when the Cleveland Museum in Ohio controversially purchased a bronze statue of a naked youth standing poised to kill a lizard on a tree or column. The figure-type is well recognised as stemming from the Sauroktonos (‘Lizard Killer’) made by Praxiteles in the mid 4th century BC. It is known from several large-scale Roman copies and numerous representations in other media. Among the copies is a famous bronze from the Albani collection which in the 18th century J.J. Winckelmann hesitantly came to consider the original. The allure of the bronze original proved a stronger temptation when the Cleveland statue was first announced, with the museum itself and several leading academics optimistically claiming that this was no late copy but the Praxitelean prototype itself.

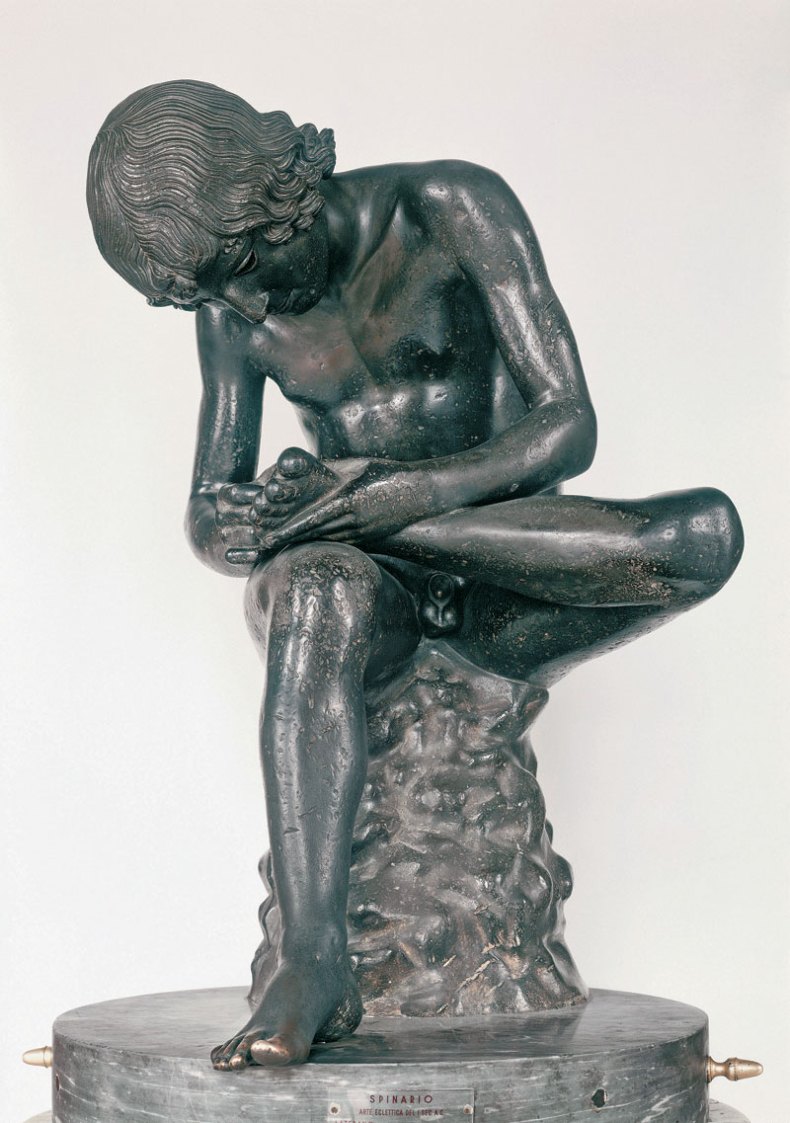

None of these controversial statues appears in a major touring exhibition that opened at the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence this spring, and now travels to the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., but the exhibition still has several dozen of the best and most interesting survivals of ancient bronze sculpture. While the ramifications of copying and replication are among its principal themes, ‘Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World’ distances itself deliberately from the preoccupation with finding classical originals. The inclusion of a ‘signed’ statue-base for a sculpture at Corinth made by Lysippos himself is a tantalising reminder of what we are missing and can never fully retrieve. By focusing on the Hellenistic world (4th–1st century BC) the exhibition turns a spotlight on to a somewhat neglected period in the history of classical bronze sculpture. It offers star works such as the extraordinary sensitive study in late Hellenistic realism known as ‘The Worried Man’ from Delos, or the famous Spinario, the thorn-pulling boy from Rome, which is one of a handful of classical bronzes never to have been buried or submerged since antiquity. But much of the excitement lies in the less well-known exhibits. Among them is the arresting bronze head of a man in a distinctive Macedonia felt hat, a kausia, which is one of several bronzes fished out of the waters around the island of Kalymnos over the last 20 years. It is probably a fragment from a portrait-statue set up to honour a Greek king. Nothing else remains of the monument. We do not know who the sitter is. Yet with its parted lips and intense stare the Kalymnos head provides the most eloquent testimony to the expressive capacities of an art tradition that appears only in glimpses through the archaeology.

Peter Stewart is director of the Classical Art Research Centre, University of Oxford.

‘Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World’ is at the Getty Center, Los Angeles, from 28 July to 1 November.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?