The world was turned upside down by Piero Manzoni in 1961, who placed a black cube on the ground and declared it a plinth, inscribed as such with socle du monde (base of the world) so that the whole earth became his sculpture. The Palestinian artist Mona Hatoum (b. 1952), who was born in Lebanon and now lives between London and Berlin, takes this inscription as the title of her own version of the work, which is a fitting opening to her retrospective at Tate Modern. Hatoum’s own Socle du Monde (1992–93) highlights her macroscopic, philosophical attitude towards the world as subject, as a fragile construction of shifting borders, informed by her family’s experience of exile from Palestine, her own from Lebanon to London in the 1970s, and her engagement with postcolonial theory, evidenced by her involvement with Rasheed Araeen and his founding of the journal Third Text in the same decade. Unlike Manzoni’s stark conceptual cube, however, Hatoum’s black box stages the world by engaging the body of the viewer through a highly visceral deployment of material. Here, intestinal nests of black metal filings bunch and curl into one another. Neither wholly natural nor manmade, the filings react to an invisible law of physics as they accumulate in dense growths, guided by magnets arranged inside the box. The effect is spine-tingling, at turns fascinating and repulsive, recalling both the post-minimalist strategies of Eve Hesse and the earlier surrealist objects of Meret Oppenheim.

Keffieh (detail) (1993–99). Mona Hatoum. Courtesy Collection agnès b; Photo Courtesy White Cube/Hugo Glendinning

This large exhibition, which survey’s Hatoum’s work from her performances of the 1980s (relayed through documentation, framed at intervals throughout), through the installations of the ’90s and their poetic subversion of minimalist structures, to her more recent large-scale sculptural work, bristles with a certain bodily charge – one steeped in the incongruity of the unheimlich. The artist’s body recurs through its detritus: hair, skin and nails are mashed into handmade paper; carefully collected pubic hair is poked into a triangular mound through holes in a garden chair; hair is embroidered onto pillows; and it is woven into a Keffieh, a traditional Palestinian headscarf worn by men. Although this work clearly teeters on the edge of the abject, by embedding it within craft traditions, Hatoum creates an uneasy picture of the body’s place within a community or history.

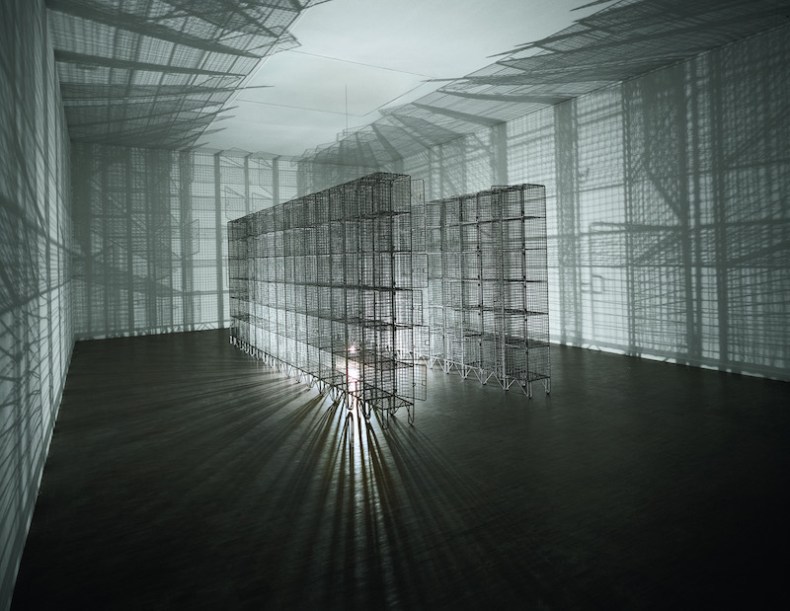

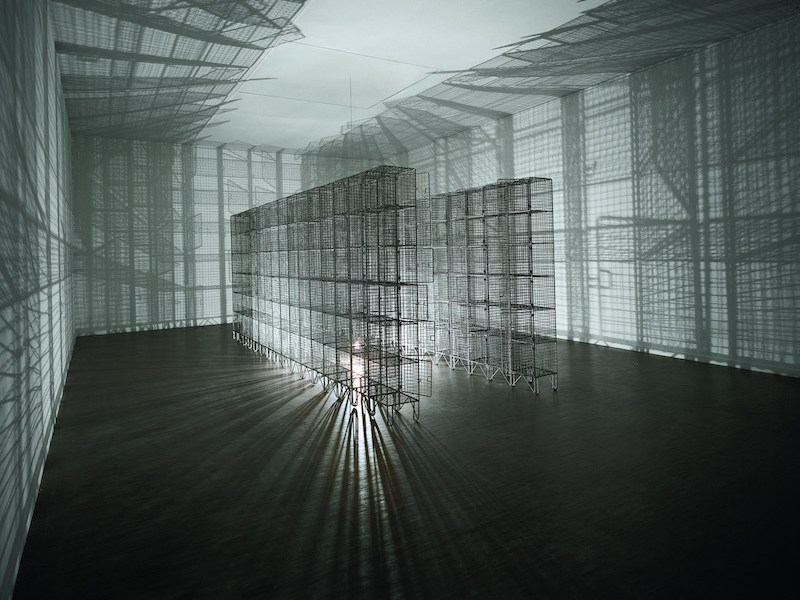

Light Sentence (1992), Mona Hatoum. Centre Pompidou, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris; Photo: Philippe Migeat

A sense of displacement or threat in Hatoum’s art, often framed in relation to her own experience of exile, is most clearly transferred to the viewer in her transformation of domestic objects such as graters, enlarged into folding screens or daybeds, their sharp barbs belying their supposed function for privacy or comfort. This work, along with earlier installations that riff off the sober cubic forms of minimalism, is often described as poetic because it largely layers metaphor and allusion rather than overtly referencing world events, or constituting an easily recognisable political stance. One of these pieces, Light Sentence (1992), comprises readymade wire lockers, stacked to form a U-shaped wall around a dangling light bulb. As the bulb teeters and sways, innumerate pencil-thin shadows are thrown about the room, creating a beautifully intricate and immersive pattern which is at odds with the penal allusions found in the wire form. The standardised locker units transform the minimalist cube from industrial to institutional marker, lit up by the ominous bulb of the interrogation room.

Hot Spot III (2009), Mona Hatoum. Courtesy Fondazione Querini Stampalia, Venice; Photo: Agostino Osio; © Mona Hatoum

While an exhibition of this size provides a welcome opportunity to engage with the physical effects of Hatoum’s work, the decision to arrange the work into non-chronological ‘zones’ is only partially successful. The importance of Hatoum’s performance as a sustained body of work in the 1980s, for example, was relegated by its display as a few examples dotted about in frames on the walls. Similarly, the playful and humorous character of much of her œuvre, in particular the smaller sculptural pieces, is lost by their proximity to more recent work, which tends towards the political one-liner, such as Hot Spot (2006), a wire globe with its continental lines illuminated in red to convey – as somewhat superfluously explained in the catalogue – ‘the dangers that loom over our planet’.

‘Mona Hatoum’ is at Tate Modern, London, until 21 August.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?