Riding in the train down to London from Eaglescliffe in Yorkshire, you see on your left the intersecting industrial networks of Stockton-on-Tees and Middlesbrough: all bridges, motorways, power stations and factories, and in the distance the bold bare hills that mark the beginning of the Yorkshire moors. It is in those hills that the remarkable painter William Tillyer now lives, but it is in the town of Middlesbrough, 75 years ago, that he was born. This dualism, between industry and nature, hard-headed modernity and luxuriant romanticism, runs throughout Tillyer’s work, from his exquisite watercolours to his robust acrylic and wire pieces.

There could be no better place to stage a major retrospective of this under-appreciated artist than at mima, Middlesbrough’s seven-year-old Institute of Modern Art. It’s a modernist jewel of a building, planted squarely in Middlesbrough’s unlovely centre. From its sheltered top terrace, on a sunny day, you can see the moors.

Tillyer explains in the exhibition leaflet that he is not normally ‘one for birthdays.’ His family persuaded him however that it would be nice to do something special and, as he puts it with Yorkshire dryness, ‘Fortunately, mima has been very generous and obliged with an exhibition.’ If this is a gift to Tillyer, an artist of tremendous vitality, integrity, and untiring creative curiosity, it is also a gift to mima. Here is a local artist, who escaped his father’s hardware business to attend the Slade, but who has remained haunted by the area’s powerful landscapes, and by the ordered neatness of human manufacture his father’s store exemplified.

Mima has given over the whole gallery to Tillyer. In the second floor exhibition of his luminous watercolours, his subject is not so much landscape itself but the grand eddies of weather that animate it. Often the heady anarchic energies of nature are held in check by some stark signal of human presence: a bridge, a balcony, the unerringly beautiful architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright’s modernist masterpiece, Falling Water. The artist is quite clear about the battle in his psyche between the lure of luminism – of the painter’s ability to conjure light-filled landscapes with a flick of pigment – and a constructivist ethic that acknowledges the limits of illusion.

Tillyer’s architectural installation, Annexe (Victory Over the Sun) 2004, embodies this tension. On one side of a standing screen an elemental splash of red paint explodes from a plausible painterly sunset, splashing over a plywood cube with a neat red circle painted on it, which is strapped tightly to the screen with thick black seatbelts. It is as if he is confronting the sun with the tools of Malevich, although Tillyer tells me that he only discovered this artistic connection (the Russian constructivist designed the costumes for a theatre piece titled Victory over the Sun in 1913) after the idea had already occurred to him.

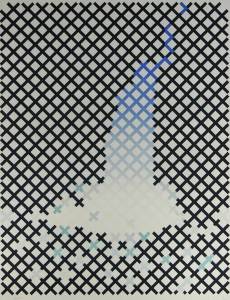

The downstairs holds a full retrospective, tracing the evolution of Tillyer’s ideas from his earliest work to his latest – an enormous canvas created with his son using watercolour and digital software, depicting High Force, a dramatic waterfall that Turner also painted. As formal devices – grids, and lattices – interact with landscapes in two and three dimensions, you sense not just the artist’s intellectual wrestling with form and content, but also a robust melancholy.

The Tyranny of The Picture Plane and Other Pressure Tools 3 (2013), William Tillyer Courtesy of Platform-A Gallery

It would be cheating to relish the consolations of wild nature without acknowledging how overlaid and tamed she is by man’s interventions. In a concurrent exhibition at Platform-A gallery (at Middlesbrough Station) wittily entitled ‘The Tyranny of the Picture Plane and Other Pressure Tools’, coloured foam is squeezed like a snake through multilayered steel grids, before its nose is flattened to create a plane. Tillyer tells me ‘I see this as a metaphor for how we live today.’ Far from being merely a painter’s painter, preoccupied with technique, Tillyer’s work is shot through with strong emotion and a desire not simply to reflect nature and human nature but to interrogate them.

‘William Tillyer: Against Nature’ is at mima, Middlesborough, until 9 February 2014.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?