Working on a project as extensive as a catalogue raisonné, one incurs debts to countless individuals and organisations. At present I am completing the final section, the ‘Acknowledgements’, trying to ensure that no one who should be thanked is forgotten. In this section I have also briefly slipped into the first person, to remark that while I think I now know exactly how to produce a catalogue raisonné, when the project began 11 years ago, this was not the case. I believe my methodology was reasonably efficient, but with hindsight I suspect I would have changed the general approach in certain respects. Of course the standard apparatus – provenance, exhibition history – must be there (it was Rebecca Daniels’ task to research these topics, drawing information out of sometimes recalcitrant owners), but I anticipate criticism of the subjective aspects of my texts; though not, I trust, of the factual information.

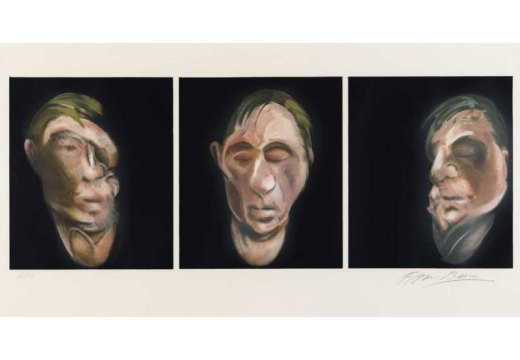

Study from the Human Body (1949), Francis Bacon. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Photo: Hugo Maertens; © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, DACS 2016

For 10 years I have met twice yearly with my colleagues on the Francis Bacon Authentication Committee – Richard Calvocoressi, Hugh Davies, Norma Johnson, and Sarah Whitfield – to review paintings submitted for our consideration. Their advice has been invaluable, and has helped set the parameters of the project. I had to deal with strange questions from ‘outside’, for example about whether I intended to include Bacon’s ‘abandoned’ paintings in the catalogue, as though it were within my remit to be selective, to weed out paintings that I (or someone else) deemed inferior or unsuitable. I have deviated from the Committee’s precepts in only one respect: at the eleventh hour I drew back from including Bacon’s so-called ‘slashed’ canvases, the paintings that he destroyed by cutting out the ‘image’, leaving only tattered fragments of background hanging from the stretchers. The ruthless destruction of failed paintings was crucial to Bacon’s creative process, but I could not bring myself to have him represented by over 50 of these scraps. Anyone so inclined is free to research them; there are 40 in Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane. The only destroyed paintings in the catalogue are those exhibited in Bacon’s lifetime (which are accessible in old catalogues) and three that were unfortunately lost in accidents while in private ownership.

Study after Velázquez (1950), Francis Bacon. Private collection. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd; © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, DACS 2016

To say that the most significant contribution in the catalogue is the illustrations rather than the words is not false modesty. To see Bacon’s entire oeuvre – 585 paintings – arranged in chronological order and illustrated in colour is a revelation. Until now the critical reception of his work has been predicated on less than half of that total, and consequently is skewed: there are not really so many ‘screaming popes’. It has been a great privilege to get close to almost every one of Bacon’s extant paintings. I was acutely aware that I was peering at paintings that very few people had ever seen, or knew only from small, rather dim black and white reproductions in the 1964 catalogue raisonné. Many of them were startling. Among Bacon’s statements about his artistic aims, the one he repeated most frequently was that he wanted to affect the viewer’s ‘nervous system’. When he achieves this his paintings induce a literally spine-tingling reaction – arguably more visceral (albeit not necessarily more profound, or moving) than experiencing Velázquez’s Las Meninas, Caravaggio’s Death of the Virgin, Rembrandt’s Self-Portrait at Kenwood – or whichever artworks turn you on.

Portrait of George Dyer in a Mirror (1968), Francis Bacon. Fundacíon Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid. Photo: Hugo Maertens; © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, DACS 2016

In seeking to explain the impact of some of Bacon’s paintings, I have invoked biographical details, all too aware that this flouts current art-historical convention. Bacon became a great painter of the human body in 1949 and made many of his groundbreaking images during the next three years. But in 1952 he met Peter Lacy, who, though seldom identified in the paintings’ titles, became Bacon’s muse for the next decade. A high proportion of Bacon’s paintings were motivated by his feelings towards Lacy, which ranged from (perhaps surprising) affection to violence or the sexually transgressive. Bacon’s partially hidden agenda was similarly personal in 10 masterpieces of George Dyer that he painted between 1966 and 1968, which chronicle his frustrations with, and ambiguity towards, his younger partner: his search for ‘the Nietzsche of the football team’ was doomed to failure. There are many ways of looking at Bacon’s paintings, but there was undeniably a psychological impulse at play. In attempting to decode their iconography I do not pretend it is possible to penetrate all of their mysteries, but their palpable presence continues to suffuse our consciousness, posing questions.

Francis Bacon: Catalogue Raisonné will be published in June by The Estate of Francis Bacon.

From the April issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?