Today, it seems, an auction house must be all things to all men, offering a sales channel to suit every vendor, buyer and work of art – be it online, through cleverly marketed ‘curated’ sales, or through private treaty sale. The latter involves an auction house accepting a work on consignment, often for several months and, instead of offering it at public auction, approaching potential buyers discreetly – the advantages being less exposure for buyer and seller, no risk of public failure at auction, and the price remaining secret. Ever savvy to new revenue streams and client needs, over the past decade auctioneers have formalised their approach and pursued private consignments more aggressively, making use of their vast international networks. All this to the chagrin of dealers, many of whom consider that the growth of auction house private sales treads on their turf and compromises the traditional function of the auction house as a platform for public sales.

Of course, auction houses have always conducted private sales; in 1779, James Christie negotiated the famous sale of the vast Walpole collection to Catherine the Great. But Christie’s and Sotheby’s now have designated private sales divisions and hold exhibitions in their private sales galleries, Sotheby’s S2 and Christie’s Mayfair. The latter, formerly Haunch of Venison, closed earlier this year, to be replaced by a gallery in the King Street headquarters. The two companies are arguably now the biggest dealers in the world as well as the dominant auction duopoly.

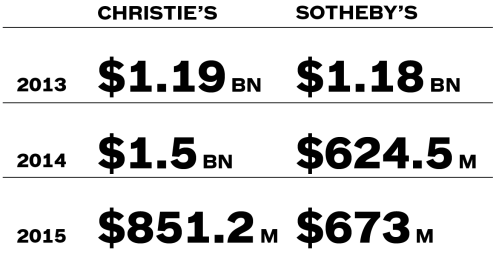

2013 was a boom year for private sales, as both houses broke the billion dollar barrier, Christie’s at $1.19 billion and Sotheby’s at $1.18 billion (up 30 per cent from 2012). But no inexorable rise ensued, and results have since fallen back. Last year, Sotheby’s recorded $673 million of private sales, while Christie’s dropped 43 per cent from 2014 to $851.2 million, with around 1,200 transactions, ‘principally because of vendors’ decisions to sell works through the public market’ according to a statement for the latter. Although Sotheby’s first quarter results for 2016 showed a 25 per cent drop in private sales from $137.5 million in 2015 to $103 million, they in fact rose as a proportion of overall net sales, from 13.3 per cent to 14.8 per cent. Despite the drop, these are still considerable sums, and the desire of auction houses to grow their private sales business shows no sign of abating. In January, Sotheby’s widely reported purchase of art advisory business Art Agency, Partners prompted intrigue: was it a statement of intent, buying in more client advisory expertise in areas like asset management and estate planning, not to mention contacts? Isabelle Paagman, Sotheby’s European head of private sales, says that looking forward AAP’s expertise ‘will certainly bolster our private sales capability’.

Total value of private sales conducted Christie’s and Sotheby’s, 2013–15

For a vendor, selling under the radar is discreet, occasionally quicker, and less risky than auction, particularly now that auction prices are published and archived online. Failure to sell in public ‘burns’ a work, so commercially trickier pieces are often better offered privately, while those that carry immediate appeal suit a competitive auction environment. ‘There’s the whole aura of an auction room, a competitive spirit that takes control of the transaction. That is often quite unpredictable,’ says Clarice Pecori Giraldi, Christie’s head of private sales in Europe, the Middle East, Russia, and India.

In an effort to prevent potentially self-defeating in-house competition for lots, at both major houses the same teams of specialists work on both auctions and private sales, with targets for each and powerful commission incentives for making private deals. However, there are also plenty of employees, Pecori Giraldi and Paagman among them, who are now largely dedicated to researching potential private sales and promoting the service. Exact charges and commission rates are not published, although, as Pecori Giraldi says, they are ‘often lower and never higher than auction fees’; at Sotheby’s, Paagman says, they are ‘flexible’.

Phillips also has grand designs on private sales. In May, it negotiated the sale of Diego Rivera’s Dance in Tehuantepec (1928) for $15.7 million to Eduardo F. Costantini, reportedly a record price for a Latin American artist. The work came up for sale at Sotheby’s London in the IBM collection in 1995, when August Uribe worked for the firm. Now deputy chairman of the Americas at Phillips, Uribe knew the work was available again and, aware Costantini had missed out on it 20 years ago, approached the Argentine collector. Costantini is a seasoned buyer at auction and privately: ‘In auctions, one feels validated by the market because someone else is prepared to bid against you. But you’re more guided by emotions so sometimes pay more. It’s difficult to assess economically.’ With the Rivera, as with many private sales, there was ‘no available price reference’, although Costantini was able to negotiate the price down.

The global reach of the major auction houses cannot be rivalled by most commercial galleries. But private sales are traditionally their domain, whether dealing on consignment as an agent (so taking commission, typically at 10 per cent), or more often buying works of art themselves, either at auction or privately, and profiting from the mark-up when they are sold on. In a sense, then, auctioneers are playing the dealer at their own game, but most dealers think they have the edge with a more personal service. Mathias Rastorfer, CEO and co-owner of Swiss-based Galerie Gmurzynska, is a critic of auction house private sales, who thinks that the lack of exact figures available ‘reveals both a reduced transparency and credibility of the auction house as a source for objective price-finding’. The growth of private sales may also be to the detriment of auction house knowledge, suggests Rastorfer, pointing to the numerous departures of longstanding department specialists at Sotheby’s this year: ‘When the business-getter is rewarded more than the traditional departmental expert with his in-depth know-how, you lose the classic auction house expertise, merely focusing on the object itself, and you replace it with salespeople focusing on the transaction.’

In France, as London dealer Stephen Ongpin points out, boundaries have always been more blurred: ‘Most experts who work as consultants for the various French auction houses are also dealers in their own right, so if a great drawing comes up, they will often first offer it privately to a handful of major clients.’ Like many dealers, Ongpin is often shown pieces privately by auction specialists if a client may be interested, but often they are ‘quite expensive’. Occasionally, these works later appear at auction with lower estimates, ‘because by then they have been shopped around a bit’.

Melanie Gerlis, art market editor of The Art Newspaper, thinks auction house private sales are part of ‘a wider trend of buyers increasingly being individuals rather than the trade’, so the houses need to offer ‘every possible service – private sales, public sales, curated sales, online sales, gallery sales, guaranteed sales – to keep them as their clients’. Now multinational operations, auctioneers are wealth managers and luxury goods specialists as much as auctioneers in a traditional sense, exploring every revenue channel to bolster the bottom line. As Gerlis says, ‘Art is increasingly being bought as a way to move money around the world, by people who would rather keep price and value as private as possible.’ Inevitably, then, few private deals are made public – with the occasional orchestrated exception, such as Christie’s handling of the recent joint sale to The Louvre and the Rijksmuseum, for a reported €160m, of Rembrandt’s portraits of Maerten Soolmans and his wife Oopjen Coppit.

And there’s the crux. Many claim to want greater transparency in the art market, yet few are prepared to break ranks. In a world that prides itself on discretion, the desire to reduce opacity inevitably comes up against the expectation of confidentiality. And while dealers complain about the smoke and mirrors of auction house private sales, to the outsider the internal machinations of their own business may seem just as mystifying. Market analysis, Gerlis estimates, is currently based on available figures that are probably only 40 per cent of the full picture. With the rise of the ‘discreet sale’, increasingly ‘anyone who would observe, analyse or predict the art market is hampered.’

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam got its rehang right?