Can single works of art communicate across the ages? We asked Ruth Allen and James Cahill to look in depth at two items – one classical, one contemporary – in their curated exhibition, ‘Classicicity’ at Breese Little, London

‘There is no antiquity.’ So wrote Francis Picabia in response to a lecture given by Vivien de Mas at an exhibition of his work at the Galerie de l’Effort moderne in Paris in 1930. At the root of his statement is recognition of the ever-presence of the classical and conviction that the arts of modernity and of classical antiquity cannot be isolated. ‘CLASSICICITY’, an exhibition of ancient and contemporary art currently at Breese Little, likewise asserts the continued relevance of Greco-Roman art, proposing that contemporary responses to the classical are as eclectic and multilayered as the classical past itself.

The show establishes multiple dialogues between the ancient and the modern, drawing out aesthetic, conceptual, and narrative parallels. Among them, two works express the perennial lure of the surreal. One was made in the long aftermath of Surrealism, the other thousands of years before it, yet both probe that strange zone between dream and reality, fact and fantasy.

Mithras relief panel, Rupert Wace Ancient Art Ltd, London. Courtesy Breese Little, London

One of the most striking ancient objects in the show is a Roman marble relief panel depicting a scene from the Mithraic Mysteries, a cult dedicated to the worship of the god Mithras. Mithras is thought to have been an Eastern deity who became increasingly popular at Rome from the 1st to 4th centuries AD, although his origins are unknown. The exact nature of his worship is as obscure, shrouded in secrecy even in antiquity. It likely involved several levels of initiation, and took place in subterranean temples known as mithraea. Built in imitation of caves, mithraea have been found across the Roman empire, from England to Palestine, and would have been filled with carved reliefs, statues, and paintings representing the god. Indeed, this relief panel would have been the focal point of just such a mithraeum, a central icon that embodied Mithras’ epiphany to his worshippers.

The relief depicts a scene known as the Tauroctony, or ‘bull-slaying’, a key moment in Mithras’ mythology and an image that is repeated across the Roman world, anticipating a theme that would resonate through later art from Goya to Picasso to Bacon. What we are given here is a window onto a mystical dreamscape where depth and scale and the reality of things perceived are no longer stable. It is an image that in its composition and arcane symbolism evokes Dalí’s marvellous landscapes or the paintings of Leonora Carrington, likewise populated by strange creatures and fantastical elements. Personifications of the Sun (Sol) and the Moon (Luna), of Sunrise and Sunset (known in Latin as Cautes and Cautopates) frame the composition, their bodies both out of scale and out of space. At the centre, Mithras plunges a blade into the neck of a bull, a sacrifice made to guarantee the fruitfulness of the universe. A dog and a serpent drink blood from the bull’s wounds while a scorpion grips its testicles, spilling the creature’s vitality into the earth.

The image hints at cosmic symbolism: not only are the Sun and the Moon represented but each of the figures depicted relates directly to a constellation: the bull references Taurus, the dog Canis Minor, the snake Hydra, the raven Corvus, the scorpion Scorpio. Loaded with astronomical significance, this image hints at time and space beyond the earthly and the corporeal. But it remains a mysterious image, its violence frozen in a moment of stasis and presented as a revelation, an icon suggestive of deep, essential meaning but that resists total comprehension. The disjointed condensation of space and the use of enigmatic symbolism disorient the viewer, the chiaroscuro-effect of the relief carving disrupting the visual field further. Perhaps in the end full comprehension only comes through communion with the god.

The Book of Two Ways (2013), Ged Quinn. Photo: Stephen White. Courtesy Breese Little, London

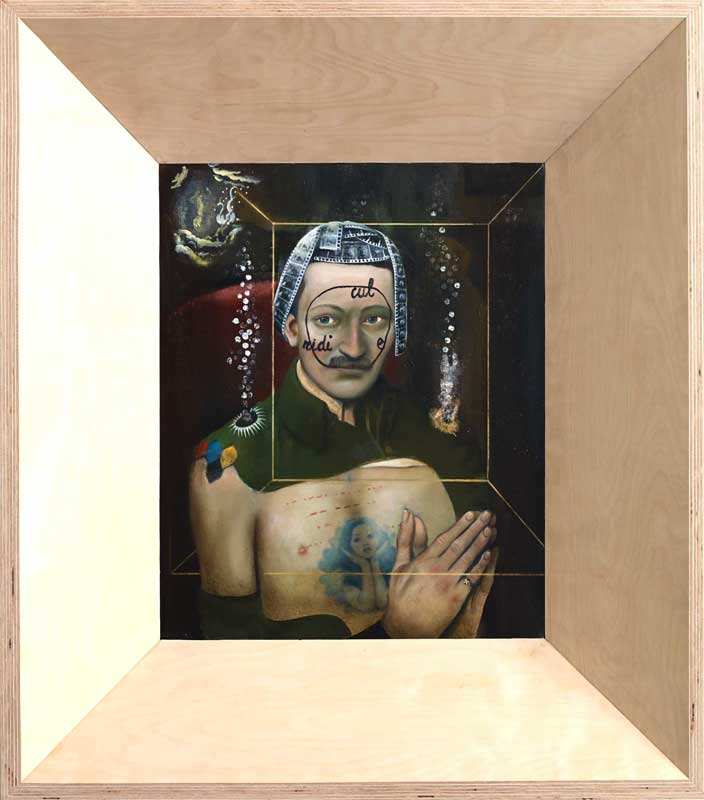

Just as enigmatic as the cult of Mithras, Ged Quinn’s The Book of Two Ways (2013) similarly merges the tangible world and its fantastical doubles. The carvers of the ancient work shroud a familiar spectacle in otherworldly events; likewise, in Quinn’s piece, we find the formulaic portrait of a man infiltrated by uncanny and incongruous embellishment. Rendered in silky sfumato, the subject holds his hands together as if in saintly prayer, gazing out serenely at the viewer from above a neat bottlebrush moustache. The trope of portraiture – devotional or commemorative, pious or pompous – affords the picture a ring of familiarity that ultimately proves deceptive. For what or whom is this a memorial? The vestiges of a military uniform cling to his shoulders and arms, yet his torso is exposed to reveal a ‘Russian criminal tattoo’ of uncertain import on his bare, pasty chest (a Siren or mermaid in royal blue). Girdling his head is a reel of photographic negatives – unreadable images within an image – and twin streams of silvery bubbles cascade up from vents in his shoulders, as if spurting from a pressurized diving suit. Within the murky waters of Quinn’s picture, we find a mass of historical flotsam and jetsam: different systems of knowledge and belief have floated improbably together, and the imperturbable mien of the man in the middle offers no guidance or resolution. In a further de-contextualising twist, the ornately detailed oil painting has been housed in a sleek modernist frame of unvarnished wood.

The painting’s title The Book of Two Ways alludes to a set of Ancient Egyptian Coffin Texts found inside a number of Egyptian sarcophagi, containing maps of the Underworld and spells relating to the journey to be undertaken by the deceased through the kingdom of the dead. Here, we enter instead a mirrored postmodern labyrinth, which finds a metaphor in the geometric frame that hovers like one of Bacon’s cages over the image, while shadows take the shape of the Minotaur in the half-light behind the man’s shoulder. A shakily drawn circle encloses his face, containing the word Ridicule in a staggered formation that seems, at first glance, to form a succinct Latin motto that we might decipher, before the actual term reveals itself Who, we ultimately wonder, is the joke on – the impassive man in the picture or the agitated historian who might try to locate and interpret him? Which is the subject of ridicule?

This painting directs us not (as does the Mithras relief) into a realm of religious enlightenment, or indeed into the secure embrace of any belief system or credo or ideology, but rather the chaotic reality of art in an age of disbelief and dissension. Quinn’s symbolism ultimately proves more elusive than that of the Mithras relief, the point perhaps being that it cannot be decoded or rationalised. His is a strangely modern kind of surrealism, its quixotic whimsies increasingly seeming like the convolutions of a well-trodden labyrinth, one from which we can never escape.

‘Classicicity’ is at Breese Little, London, until 2 April.

More Works in Focus

Work in Focus: ‘Matèria rosada’ by Antoni Tàpies (Tobias Ostrander)

Work in Focus: Surreal subjects at ‘Classicicity’

'Classicicity' installation view at Breese Little, London (5 March–2 April 2015) Photo: Tom Horak. Courtesy Breese Little, London

Share

Can single works of art communicate across the ages? We asked Ruth Allen and James Cahill to look in depth at two items – one classical, one contemporary – in their curated exhibition, ‘Classicicity’ at Breese Little, London

‘There is no antiquity.’ So wrote Francis Picabia in response to a lecture given by Vivien de Mas at an exhibition of his work at the Galerie de l’Effort moderne in Paris in 1930. At the root of his statement is recognition of the ever-presence of the classical and conviction that the arts of modernity and of classical antiquity cannot be isolated. ‘CLASSICICITY’, an exhibition of ancient and contemporary art currently at Breese Little, likewise asserts the continued relevance of Greco-Roman art, proposing that contemporary responses to the classical are as eclectic and multilayered as the classical past itself.

The show establishes multiple dialogues between the ancient and the modern, drawing out aesthetic, conceptual, and narrative parallels. Among them, two works express the perennial lure of the surreal. One was made in the long aftermath of Surrealism, the other thousands of years before it, yet both probe that strange zone between dream and reality, fact and fantasy.

Mithras relief panel, Rupert Wace Ancient Art Ltd, London. Courtesy Breese Little, London

One of the most striking ancient objects in the show is a Roman marble relief panel depicting a scene from the Mithraic Mysteries, a cult dedicated to the worship of the god Mithras. Mithras is thought to have been an Eastern deity who became increasingly popular at Rome from the 1st to 4th centuries AD, although his origins are unknown. The exact nature of his worship is as obscure, shrouded in secrecy even in antiquity. It likely involved several levels of initiation, and took place in subterranean temples known as mithraea. Built in imitation of caves, mithraea have been found across the Roman empire, from England to Palestine, and would have been filled with carved reliefs, statues, and paintings representing the god. Indeed, this relief panel would have been the focal point of just such a mithraeum, a central icon that embodied Mithras’ epiphany to his worshippers.

The relief depicts a scene known as the Tauroctony, or ‘bull-slaying’, a key moment in Mithras’ mythology and an image that is repeated across the Roman world, anticipating a theme that would resonate through later art from Goya to Picasso to Bacon. What we are given here is a window onto a mystical dreamscape where depth and scale and the reality of things perceived are no longer stable. It is an image that in its composition and arcane symbolism evokes Dalí’s marvellous landscapes or the paintings of Leonora Carrington, likewise populated by strange creatures and fantastical elements. Personifications of the Sun (Sol) and the Moon (Luna), of Sunrise and Sunset (known in Latin as Cautes and Cautopates) frame the composition, their bodies both out of scale and out of space. At the centre, Mithras plunges a blade into the neck of a bull, a sacrifice made to guarantee the fruitfulness of the universe. A dog and a serpent drink blood from the bull’s wounds while a scorpion grips its testicles, spilling the creature’s vitality into the earth.

The image hints at cosmic symbolism: not only are the Sun and the Moon represented but each of the figures depicted relates directly to a constellation: the bull references Taurus, the dog Canis Minor, the snake Hydra, the raven Corvus, the scorpion Scorpio. Loaded with astronomical significance, this image hints at time and space beyond the earthly and the corporeal. But it remains a mysterious image, its violence frozen in a moment of stasis and presented as a revelation, an icon suggestive of deep, essential meaning but that resists total comprehension. The disjointed condensation of space and the use of enigmatic symbolism disorient the viewer, the chiaroscuro-effect of the relief carving disrupting the visual field further. Perhaps in the end full comprehension only comes through communion with the god.

The Book of Two Ways (2013), Ged Quinn. Photo: Stephen White. Courtesy Breese Little, London

Just as enigmatic as the cult of Mithras, Ged Quinn’s The Book of Two Ways (2013) similarly merges the tangible world and its fantastical doubles. The carvers of the ancient work shroud a familiar spectacle in otherworldly events; likewise, in Quinn’s piece, we find the formulaic portrait of a man infiltrated by uncanny and incongruous embellishment. Rendered in silky sfumato, the subject holds his hands together as if in saintly prayer, gazing out serenely at the viewer from above a neat bottlebrush moustache. The trope of portraiture – devotional or commemorative, pious or pompous – affords the picture a ring of familiarity that ultimately proves deceptive. For what or whom is this a memorial? The vestiges of a military uniform cling to his shoulders and arms, yet his torso is exposed to reveal a ‘Russian criminal tattoo’ of uncertain import on his bare, pasty chest (a Siren or mermaid in royal blue). Girdling his head is a reel of photographic negatives – unreadable images within an image – and twin streams of silvery bubbles cascade up from vents in his shoulders, as if spurting from a pressurized diving suit. Within the murky waters of Quinn’s picture, we find a mass of historical flotsam and jetsam: different systems of knowledge and belief have floated improbably together, and the imperturbable mien of the man in the middle offers no guidance or resolution. In a further de-contextualising twist, the ornately detailed oil painting has been housed in a sleek modernist frame of unvarnished wood.

The painting’s title The Book of Two Ways alludes to a set of Ancient Egyptian Coffin Texts found inside a number of Egyptian sarcophagi, containing maps of the Underworld and spells relating to the journey to be undertaken by the deceased through the kingdom of the dead. Here, we enter instead a mirrored postmodern labyrinth, which finds a metaphor in the geometric frame that hovers like one of Bacon’s cages over the image, while shadows take the shape of the Minotaur in the half-light behind the man’s shoulder. A shakily drawn circle encloses his face, containing the word Ridicule in a staggered formation that seems, at first glance, to form a succinct Latin motto that we might decipher, before the actual term reveals itself Who, we ultimately wonder, is the joke on – the impassive man in the picture or the agitated historian who might try to locate and interpret him? Which is the subject of ridicule?

This painting directs us not (as does the Mithras relief) into a realm of religious enlightenment, or indeed into the secure embrace of any belief system or credo or ideology, but rather the chaotic reality of art in an age of disbelief and dissension. Quinn’s symbolism ultimately proves more elusive than that of the Mithras relief, the point perhaps being that it cannot be decoded or rationalised. His is a strangely modern kind of surrealism, its quixotic whimsies increasingly seeming like the convolutions of a well-trodden labyrinth, one from which we can never escape.

‘Classicicity’ is at Breese Little, London, until 2 April.

More Works in Focus

Work in Focus: ‘Matèria rosada’ by Antoni Tàpies (Tobias Ostrander)

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

Share

Recommended for you

The Winged Victory of Samothrace is back at the Louvre

One of the Louvre’s most popular sculptures is back after a 10-month restoration period

Helsinki is emerging from its winter slumber…

Tom Jeffreys reports from Helsinki on Amos Anderson’s plans for a new gallery; Kiasma’s reopening and exhibitions; and Päivi Takala’s paintings of painting

TEFAF Treasures

An early Mondrian hidden among Old Masters; Auerbach’s striking self-portrait; and a curious Collector’s Cabinet