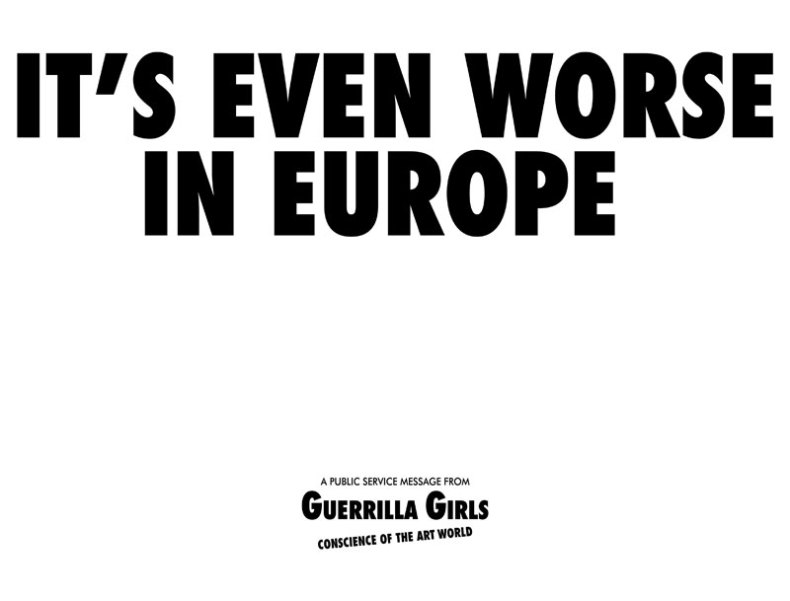

In 1986, the Guerrilla Girls – an anonymous group of feminist artists based in the USA – published a portfolio called Guerrilla Girls Talk Back. Among the 30 posters calling out sexual and racial discrimination in the art world, was one bearing the dry warning: ‘It’s even worse in Europe’. Thirty years later, the Guerrilla Girls are revisiting their famous campaign for a new exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery to ask, ‘Is it even worse in Europe?’ Amandas Ong spoke to Frida Kahlo and Käthe Kollwitz, two representatives from the activist group, to find out what has changed

With this exhibition, you’ve gone from a condemnation of the lack of diversity in European museums to a line of inquiry instead. Is it even worse in Europe? Why this change in approach, and was there anything that surprised you about your findings 30 years on?

Frida Kahlo: We got an incredible amount of data back after sending out our questionnaire to a total of 383 European museum directors, even though only a quarter responded. Some of it was completely expected: for example, when we asked if museological practices in the US were polluting Europe, most of the answers were an emphatic ‘yes’ except for the Guggenheim Bilbao. We knew that these statistics weren’t going to be optimistic for women or people of colour, but some results were fairly encouraging. At the end of the day, though, we were clear that this wasn’t just going to be a statistical analysis. We wanted people to give us their honest opinions, no matter how crazy, stupid, fantastic or in denial they were.

Käthe Kollwitz: Who would’ve guessed that Poland would be the most progressive? Women artists form 28 per cent of Polish museum collections, compared to 22 per cent on the rest of the continent. Not great, but still, all except one of the Polish collections have got women directors. And then there are these institutions that delude themselves into believing that they’re already very diverse, when the numbers speak for themselves. Who knows what’s going on in the places that didn’t write back?

Frida Kahlo: Also, we only wrote to modern and contemporary art museums and spaces. There are a good many others that are stuck with their collections and have no idea what to do with them, or how to even begin introducing diversity. What can you do when the bulk of what you can show comes from a time when 95 per cent of art was made and sold by white men?

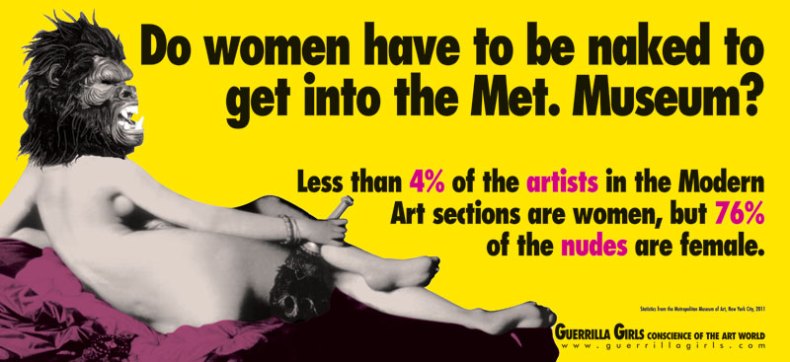

DO WOMEN STILL HAVE TO BE NAKED TO GET INTO THE MET. MUSEUM? (2012), Guerrilla Girls. © the Guerrilla Girls

How do you think your relationship with the art market has changed over the years?

Frida Kahlo: We believe in a lot of small exchanges, because we believe that these exchanges create value and meaning. We sell t-shirts, books, and posters, and we do appearances and events. We’re really proud of the fact that we’re not strictly a part of the art market, and we prefer to focus on working with educational and cultural institutions. Besides, the art market isn’t interested in us anyway. We don’t make precious objects.

Egalitarianism has always been at the core of your work, and you’ve always tried to make what you do both accessible and affordable. What are your views on social media – do you think it is a democratising force, or does it cheapen art?

Käthe Kollwitz: I think what’s great about social media is that it connects us to people all over the world who we might never otherwise meet. We have almost 100,000 followers on Facebook. There is an entire world online that cares about our work, and is inspired to carry out activist projects. They’re interested in equality and representation too, and in their own unique ways. We look at what our fans are doing on social media, and it’s hard not to be impressed by how creative they are. We get to share our work, and we get to see what other people are doing too.

In this show, and in most of your previous projects, you’ve criticised the invisibility of women in museums and cultural institutions. But that’s actually part of a larger problem of women being invisible in the formal economy. So much of women’s labour is unaccounted for in financial terms: I’m thinking about housewives in particular, and what they do within the context of the home.

Frida Kahlo: You’re absolutely right. Everything that’s wrong with the art academy also applies to the world in general, and I’m not just speaking in terms of women-specific issues, I’m also talking about the way we treat people of colour. Income inequality in the art world is shocking. All you have to do is to go to an auction and look at the prices. Women get about 17 per cent to 20 per cent of what white men get, and you see the same kind of wage inequality being talked about in other industries. But I have to say that I don’t think the problem is as much women being invisible, as it is that white men have a monopoly on everything. The art world has always been about patronage, and that’s a real problem, because it breeds corruption. In the US, museums are often run by trustees, many of whom are art collectors themselves. So they decide what to buy and what to show, and nobody questions it because there’s this stupid concept of artistic license. It’s getting worse all the time.

Käthe Kollwitz: We’re also noticing a proliferation of private museums all over the world, not just in the US and Europe. That’s not democratic. If we allow the same few wealthy old men to tell us what our history is, then how are we better off from hundreds of years ago, when people lived under kings and queens?

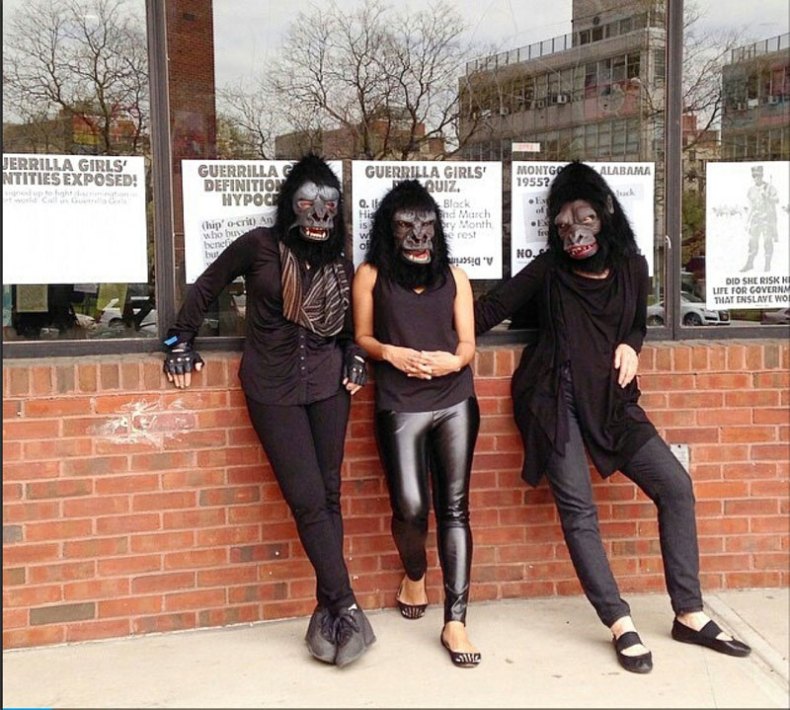

Guerrilla Girls (2015), Andrew Hindraker. © the Guerrilla Girls

So why do you think the art establishment still isn’t interested in fostering inclusion and diversity?

Käthe Kollwitz: People are totally interested. It’s just the powers that be that are stubborn in their ways, but if you go to most cultural institutions you’ll find a lot of well-meaning people who make it their mission to promote diversity. But on the whole, these places are just not doing a good enough job.

What do you think is the greatest injustice that women today contend with?

Frida Kahlo: All sorts of injustices, including what you were saying earlier about women’s work being undervalued. Then there’s sexual slavery all over the world. I can’t even tell you what I think the biggest problem is. They’re all terrible.

Käthe Kollwitz: For me it’s definitely violence in all forms: economic, physical and sexual. Female babies that are not even born, because they’re not wanted: that’s a form of violence too, even before life begins.

If you could say just one thing to Donald Trump, what would it be?

Frida Kahlo: Donald Trump! Give up your gangster ways!

Käthe Kollwitz: God, I don’t know. I don’t want to say anything to him.

‘Is It Even Worse in Europe?’ is at the Whitechapel Gallery from 1 October to 5 March; the Guerrilla Girls will also lead a week-long major project at the Tate Modern from 4 to 9 October as part of the Tate Exchange.

It’s even worse in Europe (1986), Guerrilla Girls. © the Guerrilla Girls

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?