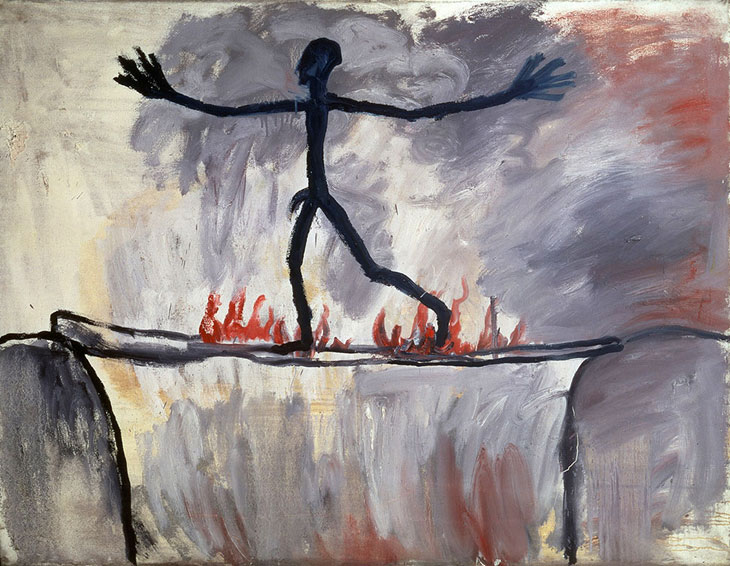

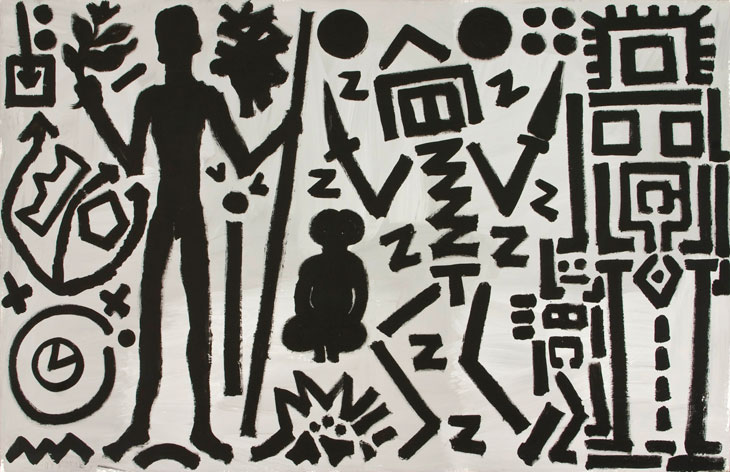

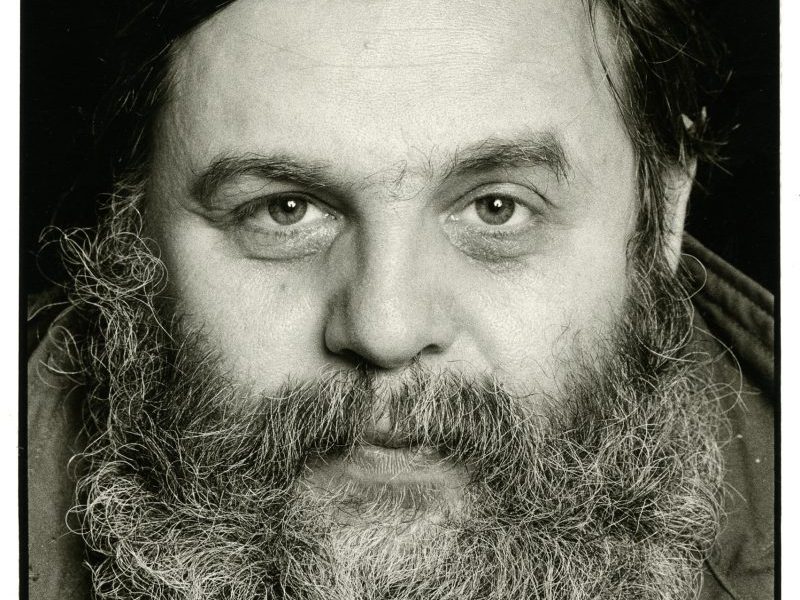

A.R. Penck was a thoroughly mysterious artist – at least for those, like myself, who never met him. Some clues to his elusive, underground character can be drawn from his early life, but still remain obscure. Nowadays it seems impossible to imagine what it would be like to witness the destruction of an entire city by bombing, as Penck did at the age of six, from his parents’ garden on the outskirts of Dresden. Nor what it would be like to launch a career as an artist devoted to Picassoesque modernism in East Germany, where the officially sanctioned style was Socialist Realism. Penck considered his ‘Standart’ paintings, constructed of arcane symbols and stick-figures, as a ‘positive contribution to Socialism’ – but he must have known that their real value was oppositional, agitational.

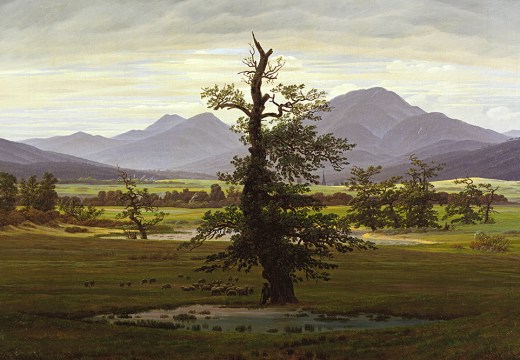

Der Übergang (The Crossing) (1963), A.R. Penck. Collection Ludwig, Ludwig Forum für International Kunst, Aachen

There were many questions I would have liked to ask Penck. What, for example, went through his mind meeting the gallerist Michael Werner in the woods outside Berlin, passing him rolled-up canvases for Werner to smuggle back and sell in the West? And what were his thoughts on the night of 3 August 1980, when he crossed the inter-German border on foot, defecting to the West. Was it a sense of liberation? Was capitalism a daunting prospect? Did he imagine he would ever return?

Welt des Adlers IV(Eagle’s World IV) (1981), A.R. Penck. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, New York and London

Penck’s restlessness and sense of being an eternal dissident radiate from his work. His stick-man paintings have such an intensity of human drama and economy of symbolism that I always imagined them being sent into outer space to enlighten extraterrestrial beings as to life on earth. The same restlessness is evident in his endlessly inventive sculpture using cheap artless materials, cardboard boxes, discarded packaging, studio scraps – displayed to great effect at Michael Werner’s London gallery last year. His many artist books and album cover designs were among the works included in the retrospective held at the Musée d’art moderne in Paris just under a decade ago, a thrilling portrait of an underground artist.

I admire his work, and what I know of his life, for his relentless and bloody-minded pursuit of freedom. This, I think, is how he will be remembered best – as a vital example of what making art and being an artist can mean.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?