Several museums have received wonderful gifts this Christmas… Here are some of the most significant acquisitions to be announced at the end of 2015.

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

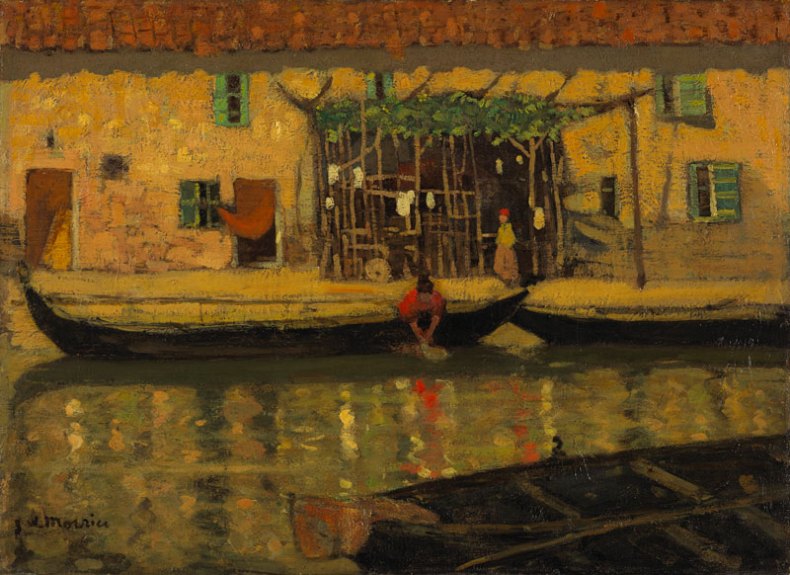

Fifty works by James Wilson Morrice

The Canadian collector, dealer and J. W. Morrice enthusiast Ash K. Prakash has donated a large group of the artist’s paintings to the National Gallery of Canada. Morrice, who settled in Paris in 1890 and enjoyed a successful international career, is one of Canada’s best loved artists. Even before the $20 million gift was made, the gallery boasted the largest collection of Morrice’s works in the world; they’re swiftly developing something of a monopoly over him. A major retrospective is planned for 2019.

Vancouver Art Gallery

Look in my face; my name is Might-have been; I am also called No-more, Too late, Farewell (2010-ongoing), Geoffrey Farmer. Plus various other contemporary works

The Vancouver Art Gallery mounted an exhibition of Geoffrey Farmer’s work last summer. Now the artist, who will represent Canada at the 2017 Venice Biennale, has donated one of his landmark pieces to his home city. Look in my face… is a computer-generated montage of tens of thousands of images and sounds drawn from public archives, and is intended as a reflection on shared cultural narratives and memories. Farmer’s is just one of many contemporary works acquired by the gallery recently, including pieces by Sonny Assu, Reena Saini Kallat and Mark Ruwedel. All in all, a good month for Canada.

Look in my face; my name is Might-have-been; I am also called No-more, Too-late, Farewell (installation view; 2010–ongoing), Geoffrey Farmer. Photo: Rachel Topham, Vancouver Art Gallery

The Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington DC

New works by Ragnar Kjartansson, Hito Steyerl and Mary Weatherford

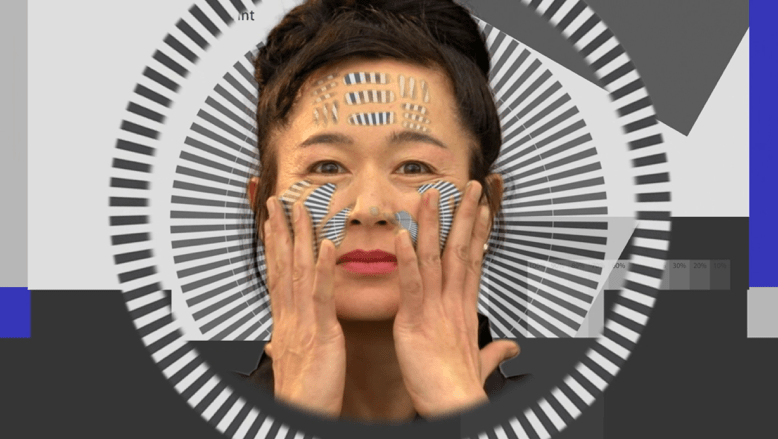

It’s been a decade since the Hirshhorn opened its ‘Black Box’ space dedicated to video and film art. Adding works by Ragnar Kjartansson (who featured on our 40 Under 40 Europe in 2014) and Hito Steyerl to the collection cements the museum’s moving image credentials. Kjartansson’s S.S. Hangover (2013–14) documents his famous performance on a boat at the 2013 Venice Biennale. Steyerl’s How Not to Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File (2013) is a characteristically sharp exploration of the role of images in contemporary life. Mary Weatherford’s neon-highlighted painting Engine (2014), meanwhile, looks back to 20th-century colour field and abstract expressionist styles, updating modernism for the new century.

How Not to Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File (film still; 2013), Hito Steyerl. Image courtesy of the artist and Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York

Nationalmuseum, Sweden

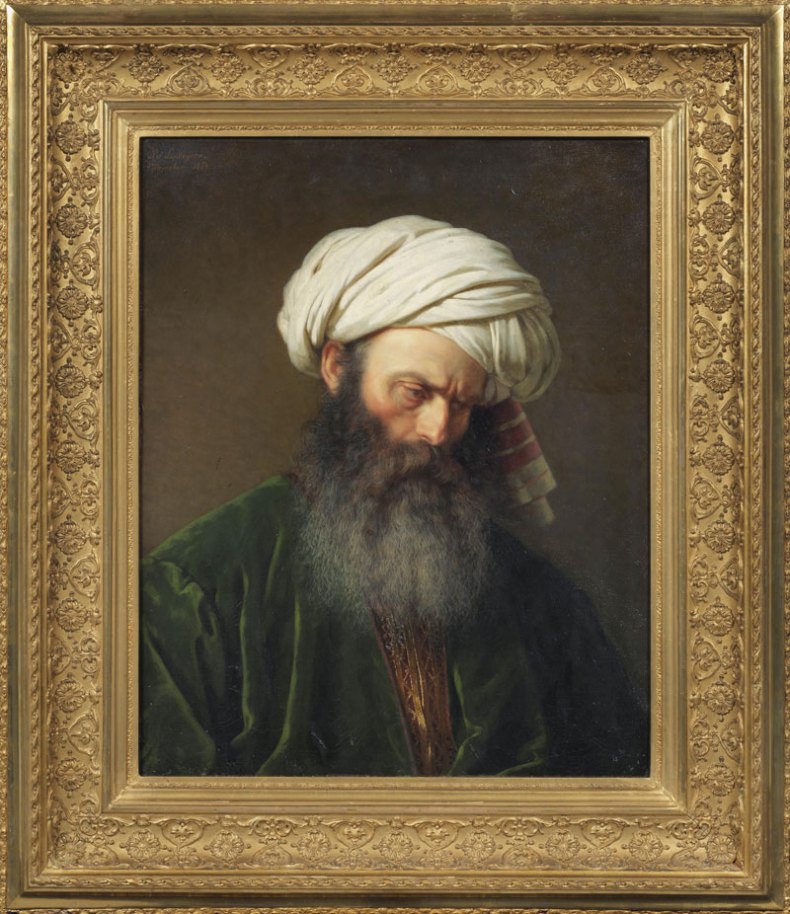

Study of a man in Turkish dress (1854), Amalia Lindegren

Amalia Lindegren produced this subtle study of an unknown man while visiting Munich on a government scholarship. It was shipped back to Sweden to be offered as a prize in the Swedish Association for Art’s Christmas raffle, and was won by a man called Fredrik Bergwall, whose family held onto it ever since. Now the work takes a place in the national collection alongside a second, exemplary piece by the artist, Girl with an Orange (1855).

Musée du Louvre, Paris

The left wing of the Dreux Budé Triptych showing The Betrayal and Arrest of Christ (c. 1450), probably by André d’Ypres

The Louvre paid £965,000 for this small panel, which was commissioned in the mid 15th century by the prominent Parisian merchant Dreux Budé. The triptych’s three main panels are scattered – the central one is in the Getty, Los Angeles; the right wing is in the Musée Fabre at Montpellier – but the Louvre’s new purchase will join another work, The Crucifixion of the Parlement of Paris, which is believed to be the design of the same artist.

Saint Louis Art Museum

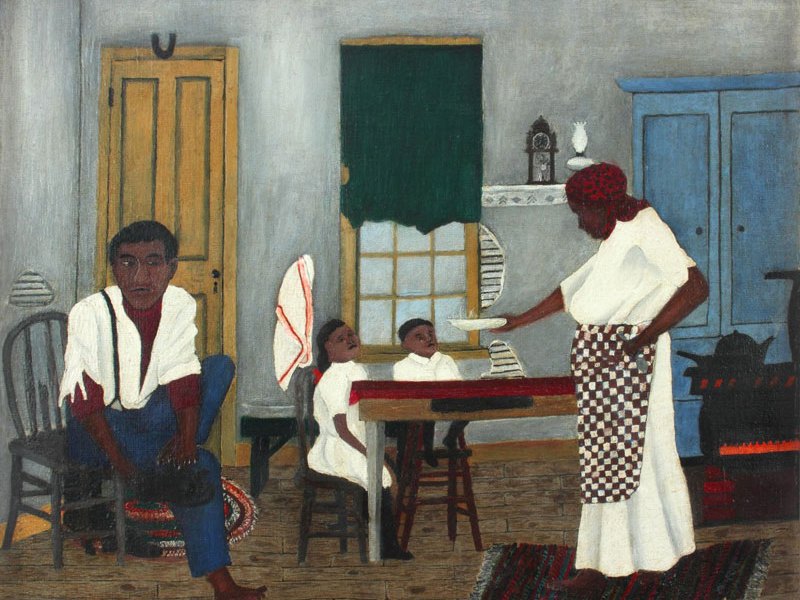

Sunday Morning Breakfast (1943), Horace Pippin

African American artist Horace Pippin’s Sunday Morning Breakfast balances an intimate domestic subject with strong modernist design. Pippin, who took up painting after losing the use of his right arm (he was shot in the shoulder during active service in the First World War) trod a line between modernist and folk art traditions: ‘The painting will serve as a bridge within the broader American collection to reveal complex and often-overlooked relationships between styles and practices’, M. Melissa Wolfe, the museum’s curator of American art, explained. The museum paid the New York-based Alexandre Gallery $1.5 million for it.

Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston

20 works by 12 female artists

Eva Hesse, Kara Walker and Carol Bove are among the artists featured in this group of works, donated by the collector, philanthropist and vice chair of ICA Boston’s board of trustees, Barbara Lee. The 20 new works are in addition to 43 pieces of art by women that Lee donated to the museum in 2014. It’s one of a few concerted attempts we’ve seen recently to address the underrepresentation of women artists in major institutions.

Tate, UK

Eighteen print editions by Ed Ruscha

The US Pop artist Ed Ruscha, known for his emblematic depictions of modern America, has given a major group of his printed editions to the Tate collection – augmenting an already impressive group of his paintings, drawings and prints donated by the art dealer Anthony d’Offay in 2008. Nicholas Serota called the works ‘a wonderful Christmas present to the whole nation’. And it’s a gift that keeps on giving: Ruscha has also promised the institution an impression of every print he creates from now on.

View the rest of this series

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam got its rehang right?