Hung from the central rafters of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, the heavy jute sacks of Ibrahim Mahama’s installation, Fracture, obscure the bright Mediterranean sun that typically floods the building. Twenty-nine-year-old Mahama works primarily with jute – the fibrous sacks used to transport cocoa and coal around and out of his native Ghana – layered and sewn together to create large-scale architectural coverings. The sack tapestries wear a political history, one of uncertain economies and malleable commodities; their stamped, worn surfaces come to represent the invisible workforce that keeps them moving.

In Tel Aviv, Mahama’s work takes on a new layer of political and site-specific significance. Fracture, in its jagged stitching, is a dark, all-encompassing reaction to the fissures in Israel’s socio-political landscape, and the continued, looming presence of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. But the installation also functions as an introduction of sorts – the tunnel of darkness it creates leads to ‘Regarding Africa’, the Tel Aviv Museum of Art’s corresponding, expansive survey of contemporary African art and Afrofuturism.

Installation view of ‘Regarding Africa: Contemporary Art and Afro-Futurism’ at the Tel Aviv Museum of Modern Art

Stepping out of the shadow of Mahama’s installation and into the exhibition space takes a moment of readjustment, not unlike venturing into the midday sun after having the living room curtains drawn all morning. The weighty history of the Ghanaian sacks is traded for sound, screen, and sculpture, a sprawling array of mixed-media made in and about Sub-Saharan Africa since the 1960s.

Curator Ruth Direktor has used the exhibition as a platform to explore varied expressions of Afrofuturism, a term that grew out of the work of experimental African-American musicians in the 1960s. At that time, composers like Chicago-based Sun Ra infused hard bop with nods to his African heritage, and began mixing it with a sci-fi aesthetic. Throughout the second half of the 20th century, this revolutionary relationship between past and imagined future took hold across all modes of black artistic expression in the diaspora. In her 2013 book, Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy, Nigerian artist Ytasha Womack describes its far-reaching influences: ‘Both an artistic aesthetic and a framework for critical theory, Afrofuturism combines elements of science fiction, historical fiction, speculative fiction, fantasy, Afrocentricity, and magic realism with non-Western beliefs.’

‘Regarding Africa’, the first institutional exhibition of its kind, brings together 28 artists whose work criss-crosses the Sub-Saharan continent, exploring the trappings of colonial history and redefining the landscape. The works are plentiful and colourful, and often in front of the lens. Alongside large paintings by Chéri Samba and the war-like drawings by Abu Bakarr Mansaray, photographs and video works dominate the space.

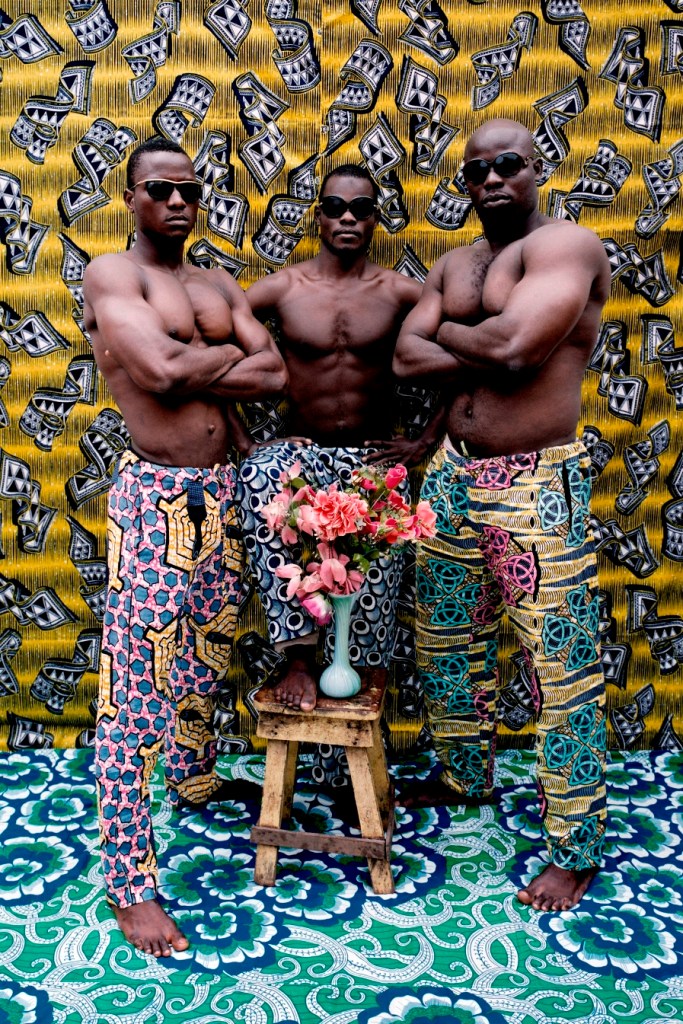

Leonce Raphael Agbodjelou is one Afrofuturist artist who has remixed the studio-photography heritage of his native Benin. Born in 1965 to one of Porto-Novo’s most respected studio photographers, he learned the trade with his father, who, despite his black and white medium, insisted on posing his subjects in front of colourful textiles and prints. Agbodjelou’s frames now explode with colour, and his Musclemen series (2012) injects a masculine-feminine humour into the local studio tradition, where shirtless bodybuilders square off with the camera, surrounded by bright patterns and adorned with flowers.

Untitled (2012), from the Musclemen series, Leonce Raphael. Courtesy Tel Aviv Museum of Modern Art; © the artist

Two short films, both by Nairobi-born artists play out on nearby walls, interpreting the future in radically different ways. Where Wangechi Mutu’s Amazing Grace sees the artist walk into the sea, dressed in white and slowly singing the hymn in her native Kikuyu, Wanuri Kahiu’s film Pumzi imagines an East African post-apocalyptic reality, filled with sci-fi imagery and disconnected from any natural landscape.

The exhibition also touches on the relationship between Israel and Africa, one that is sometimes fraught with political tension. In recent years, a growing community of migrant workers and refugees from Eritrea and Sudan have taken up residence in southern Tel Aviv, something that the right-wing government led by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has recently referred to as illegal ‘infiltration’.

‘Regarding Africa’ turns this idea on its head, including work by Tel Aviv-based, Eritrean photographer Abiel Amanuel, who runs the local Sun-Sol studio, as well as examinations by Israeli artists into the migrant community. Luciana Kaplun’s three-video installation entitled Who is Atallah Abdul Rahman el Shaul? is bizarrely enchanting, springing from a story she heard while working with Sudanese and Eritrean children at the local library in Tel Aviv. The films, centred around a rumour that traces Netanyahu’s birth to a village in northern Sudan, is a three-location homage to Nollywood, with storytellers from Sudan, Ghana and Nigeria recounting the legend. It is truly absurd – but coming away from the darkened viewing room, surrounded by so many challenging and redefining works, the postcolonial narratives take on a unique resonance when you remember you’re in Israel.

‘Regarding Africa: Contemporary Art and Afro-Futurism’ is at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art until 27 May 2017.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam got its rehang right?