In the late summer of 1928 the artists Christopher Wood and Ben Nicholson, on holiday in Cornwall with friends, took a day trip to St Ives. Through the open door of a cottage they noticed some paintings of ships and houses nailed to the walls. Alfred Wallis, a 73-year-old former sailor, labourer and storekeeper, had begun painting around three years earlier (‘for company’, he said, after the death of his wife), using any surface that came to hand, often irregularly shaped pieces of cardboard. He had no training, and not much technique – no idea of perspective, for example – but Wood and Nicholson found in his work a directness of vision and a natural sense of rhythm and colour, untrammelled by fashion or academic preconceptions; they saw in him a freedom.

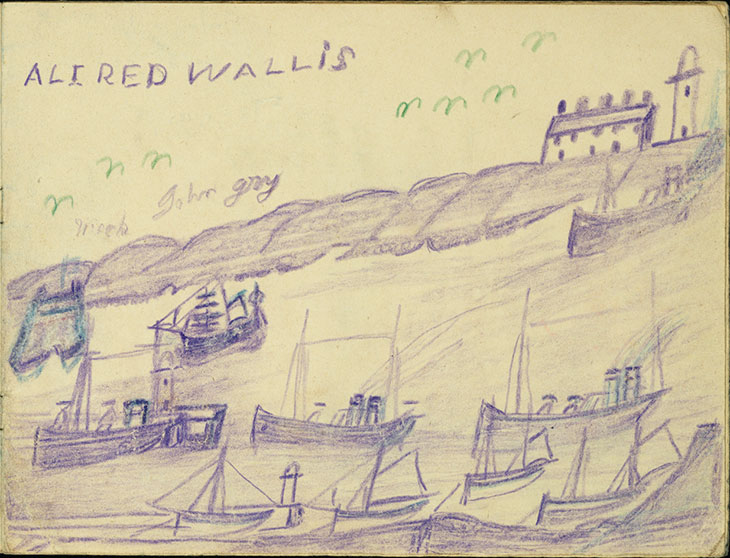

Page from Castle Book (1941–42), Alfred Wallis. Lent anonymously, all rights reserved

Wood and Nicholson spoke of Wallis, half-jokingly, as their master; they tried to paint like him and promoted his work to their friends. Among these was Jim Ede, a curator at the Tate Gallery. Wood killed himself in 1930, and Nicholson’s artistic interests moved on, but Ede kept the faith. Over the next few years, he bought more than a hundred paintings from Wallis, and corresponded with him regularly; so that Kettle’s Yard, the house-cum-gallery that Ede presented to the University of Cambridge in 1966, has an unrivalled collection of his work – too many to be displayed at once. (The best short guide to Wallis’s place in 20th-century art is Alfred Wallis: Ships and Boats, published to accompany an exhibition at Kettle’s Yard in 2012, which includes essays by Nicholson and Ede.)

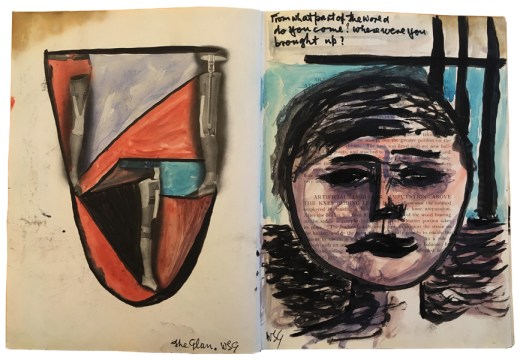

There are always several Wallises on show in the house, among the carefully preserved furniture and objets that Ede and his wife Helen left behind, and more line the walls of the reading room extension; most are kept out of sight in the reserve collection. ‘Alfred Wallis Rediscovered’ brings together in the gallery’s newish exhibition space a number of those rarely seen paintings, together with some of the works usually on show in the house and loans from elsewhere. It has a couple of claims to novelty: some letters to Ede (Wallis’s spelling is poor but his hand is surprisingly elegant, given the clumsy capitals with which he signed his work); and three sketchbooks which Wallis filled not long before his death in 1942, when he was living in an institution near Penzance, and which have not been shown in public for more than 50 years. Alongside the books, spread open in a display case, is a video of a latex-gloved hand turning the pages to show off every drawing.

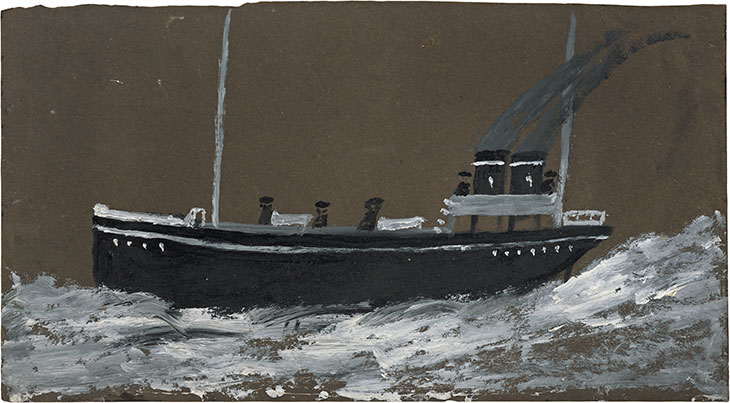

The Death Ship (1941–42), Alfred Wallis. Courtesy Kettle’s Yard, University of Cambridge

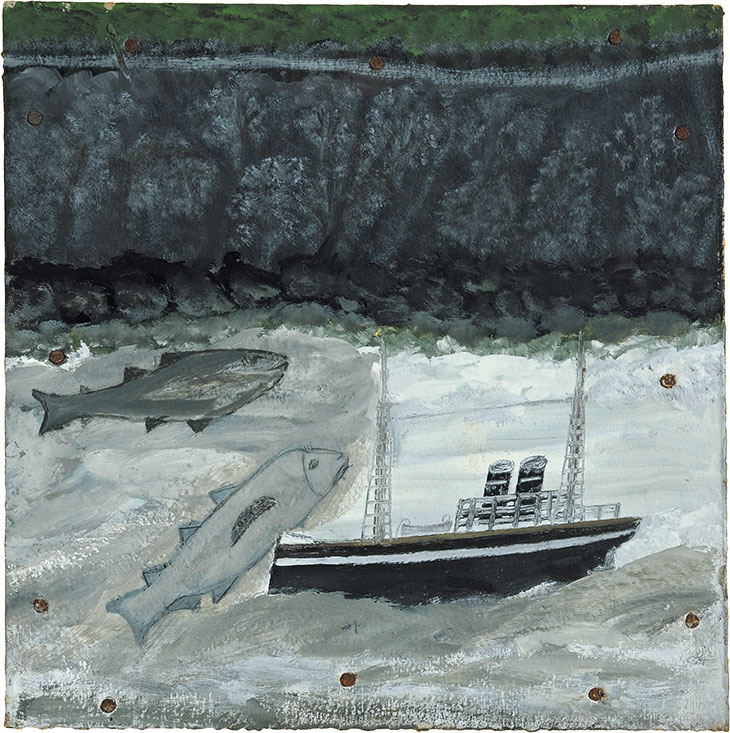

I have always been in two minds about Wallis. A lot of his work has charm – the flatness of perspective and the blocks of colour make it ideal for reproduction on the tea towels, fridge magnets and face masks (a reminder that it’s 2020) on sale in the Kettle’s Yard shop; less of it gives me a glimmer of what Nicholson and Wood saw. I admired the stark Death Ship (c. 1941–42), black with a white line along its length, on a turbulent white-and-grey sea painted on dark card – the title was Ede’s, not Wallis’s, but it suits. There is an enigmatic, mythic quality to Land, fish and motor vessel (c. 1932–37) – a pair of Jonah’s great fish or leviathans swim about the boat but it is impossible to tell if they are predatory or friendly (the critic Herbert Read quoted Wallis saying that every boat has ‘a beautiful soul shaped like a fish’: perhaps that’s a clue). I like the diagrammatic precision with which he draws the rigs of different boats – lugger, brigantine, barque – though it’s only occasionally that you feel any sense of tension in the canvas as the wind fills it. In general, his things (boats, lighthouses, little square houses) are less interesting than the areas of paint that surround them, the waves and clouds, in which the murky, worked-over swirls and dabs seem far less naive.

Land, fish and motor vessel (c. 1932–37), Alfred Wallis. Courtesy Kettle’s Yard, University of Cambridge

But if individual paintings can be rewarding, Wallis en masse can seem oppressive, with his consciously limited palette of marine enamels, largely black, white, brown, blue, green – it comes as a shock to see a boat with orange sails in St Ives Bay with Godrevy (no date): a distrust of too much colour was the nearest Wallis came to a theoretical stance. The current exhibition includes one of the paintings Nicholson made under Wallis’s influence, Cornish Port (1928), in which a tiny schooner sails off a headland made of streaks and patches of colour, on which nestle little blocky houses with plain black splodges for windows. Among all the Wallises, the variety of tone here – the brightness of the blue in the sky – comes as such a relief to the eye. The freedom Nicholson saw in Wallis was really a novel set of limitations; perhaps that’s what freedom mostly is. The sketchbooks bear this out: there’s a new looseness to Wallis’s drawings in, mostly, red and green crayon; they feel closer to fun. Sven Berlin christened some of Wallis’s late work his ‘death paintings’, but it is hard to detect here any ‘late style’; however static his paintings can be, they are alive.

Museums and galleries in England are closed from 5 November due to Covid-19. For more information on ‘Alfred Wallis Rediscovered’ (scheduled to run until 24 January 2021), visit the Kettle’s Yard website.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?