This summer Leighton House Museum stages its most daring exhibition yet: ‘Alma-Tadema: At Home in Antiquity’. It is an impressive undertaking, featuring over 130 works by Laurence Alma-Tadema (1836–1912), his family, and circle. But it is not just its scale that makes this a bold exhibition. As the first major show in London dedicated to Alma-Tadema since 1913, it is an attempt to rehabilitate the artist in the public’s affections. Although he was one of the leading painters of the Victorian era, his critical reputation went into precipitous decline immediately following his death, after which his work has been largely ignored, if not reviled.

The exhibition’s title refers to Alma-Tadema’s distinctive take on classicism. In his paintings he eschews the epic in favour of the everyday, reimagining how domestic life might have looked in the ancient world. His creations are not entirely fanciful; he aimed to achieve a high degree of archaeological authenticity by meticulously copying from artefacts, replicas, photographs, and book illustrations. His paintings were commercially successful, however, not simply as reconstructions of the past, but also because of the way they implied parallels with the present. Life in imperial Rome was not greatly different from life in imperial Britain, Alma-Tadema seemed playfully to suggest. But he also offers escapism: transporting his audience from smog-bound London to the sunlit Mediterranean, where everyone appears to be always on holiday, enjoying untroubled lives. It is a refreshing vision, but one the critic Roger Fry dismissed as ‘highly scented soap’.

The Roses of Heliogabalus (1888), Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema. © Perez Simon Collection

Alma-Tadema had good business sense and understood his market. Born in the provincial Netherlands, he received his artistic training at the Royal Academy in Antwerp, before launching his career in Brussels. But it was when he moved to London in 1870 that he met with real success, both financially and socially. He became a British citizen in 1873, a Royal Academician in 1879, was knighted in 1899, and awarded the Order of Merit in 1905.

‘At Home in Antiquity’ has a second meaning, referring to Alma-Tadema’s own domestic arrangements. He invested a considerable portion of his wealth in the refurbishment and decoration of two remarkable studio-homes in London, which he shared with his second wife, Laura, and his daughters. Each was lavishly furnished with an eclectic mix of styles and exotic materials. Laura, who was a talented artist in her own right, was a collaborator in this creative enterprise, as well as his muse and model. The exhibition explores the close relationships between their family life and their creative lives, and reveals how their homes became expressions of their taste and artistic personalities, as well as sources of inspiration for their paintings.

Sadly, neither of the interiors of two homes survives today, but we get some impression of what they would have looked like from photographs, personal belongings, drawings, and paintings, including a number by Laura and by one of the daughters, Anna. And Leighton House, the magnificent studio-home of Frederic Leighton, Alma-Tadema’s friend and fellow Academician, provides a fitting venue for the exhibition. At the end of the 19th century there was a short-lived craze for lavish artists’ homes in London, described as ‘private palaces of art’, of which Leighton House is now the best surviving example.

The second of Alma-Tadema’s London residences – ‘Casa Tadema’ – in its day rivalled Leighton’s home. Extensively remodelled as a Roman-style villa, it is said Alma-Tadema spent £70,000 on Casa Tadema’s refurbishment, the equivalent of £1 million today. At the heart of the building was his double-height studio, which had a half-domed ceiling expensively clad in aluminium to reflect silvery light, redolent of the Mediterranean, into the room. Many of the settings of Alma-Tadema’s paintings were modelled on the open-plan interiors of his home. He had a love of complex architectural arrangements, and a recurring device in his pictures is the suggestion of a larger space opening beyond the field of vision and glimpsed through a doorway or window, down a staircase, or over a balcony.

Alma-Tadema typically populated these interiors with women rather than men. He depicted them not doing a great deal: lost in reverie, reclining on marble seats, or smelling bouquets of flowers. Women and flowers: it quickly becomes repetitive, and he was criticised in his own day for turning out the same stock imagery.

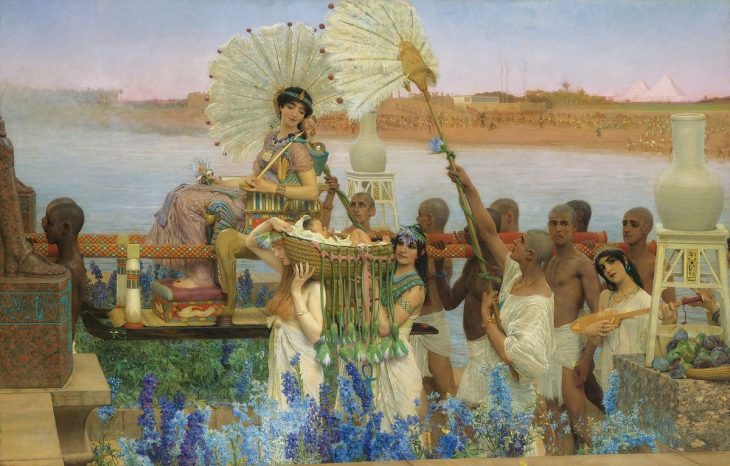

In one of his most famous paintings, The Roses of Heliogabalus (1888), the women in the foreground are being suffocated under a cascade of flowers. It is meant to be a depiction of an atrocity: the deranged tyrant Heliogabalus murdering his party guests in the most beautiful way imaginable. But Alma-Tadema avoids the horror, making it all about the prettiness of the rose petals.

A Coign of Vantage (1895), Lawrence Alma-Tadema. Private collection. Wikimedia commons

One criticism levelled at Alma-Tadema’s art was that it lacked moral seriousness. In Coign of Vantage (1895), three beautiful women look from a high viewpoint on a galley in the sea far below. The implied narrative is of the women anxiously awaiting their menfolk returning from war or maritime adventures. Yet these three don’t seem particularly bothered: one stretches languorously, the other two look down as if watching fish in a pond. It is a beautifully painted picture – infused with warm sunlight, but emotionally cold. Within a couple of years of Alma-Tadema’s death Europe was at war and young men were being sent off to fight. It is not hard to see how, in this changed cultural climate, Alma-Tadema’s pictures started to look soulless and out of step with the times.

Alma-Tadema’s art was not, however, completely forgotten in subsequent decades. The visual language he created found a new lease of life in the medium of film. When Hollywood film designers came to recreate the Roman world for Biblical and historical epics, it was to Alma-Tadema’s paintings they turned for inspiration. An audio-visual presentation in the exhibition explores these connections, looking at his influence on films such as Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments (1956) and Ridley Scott’s Gladiator (2000).

There is much that is entertaining in the exhibition, and perhaps the best way to approach Alma-Tadema’s art is not to take it too seriously. The theme of domesticity (and the setting of Leighton House) provides a window into the world he inhabited, and situates his art in the cultural milieu of Victorian London. But the exhibition also reveals the commercially successful painter as an artist with a surprisingly modern eye, whose art was shaped by the new visual conventions of photography, and who was not afraid to experiment with unusual formats and compositional approaches. He deserves to be loved once again.

‘Alma-Tadema: At Home in Antiquity’ is at Leighton House Museum until 29 October 2017.