In Spain, France and Italy, the political and social transformations of the 18th century led these three very different artists – this show of 100 works contends – to develop both a freer handling of paint, and a more fantastical choice of subject matter. Find out more from the Hamburger Kunsthalle’s website.

Preview the exhibition below | View Apollo’s Art Diary here

Christ in Gethsemane (after 1753), Giovanni Battista Tiepolo. Photo: Elke Ward; © Hamburger Kunsthalle/bpk

In this painting, Christ lies in the garden of Gethsemane, where he was betrayed and arrested. Tiepolo’s clever play of light and dark here communicates to the viewer Christ’s state of mental anguish – an example of the Italian painter’s skill at engaging his viewers imaginatively in his paintings.

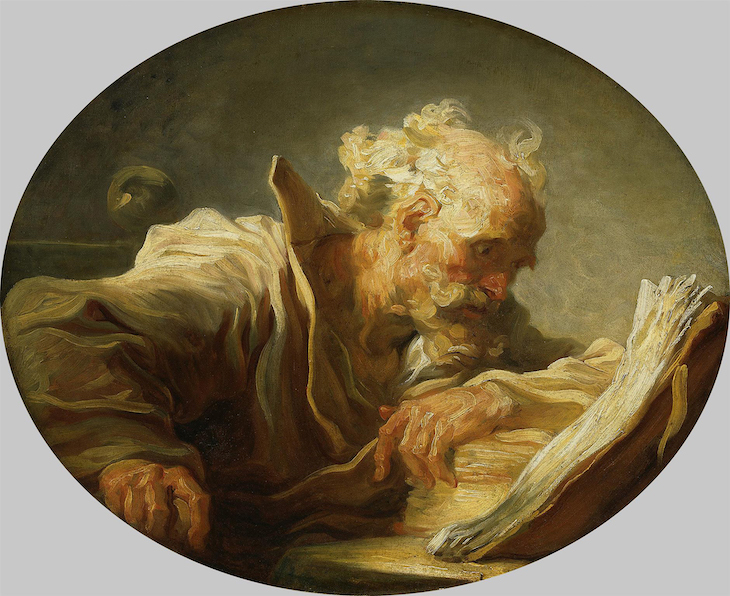

The Philosopher (c. 1764), Jean-Honoré Fragonard. Photo: Elke Ward; © Hamburger Kunsthalle/bpk

In this early painting by Fragonard, the intensity with the philosopher directs his eyes towards his book is echoed in the impassioned flair of the brushwork with which his scholar’s robes and wisps of white hair are depicted. Characteristically exuberant, the work pre-empts Fragonard’s later, famous series of ‘Fantasy Portraits’, in arguing above all for the intensity of experience that is to be found in the imagination – a belief the painter shared with Denis Diderot, the pre-eminent French philosopher of the Enlightenment.

Don Tomás Pérez Estala (c. 1795), Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes. Photo: Elke Ward; © Hamburger Kunsthalle/bpk

Stripped of all incidental detail, this depiction of the engineer Tomás Pérez is typical of Goya’s portraiture. All of the force of the painting comes from the eyes, the heavily set features, and the slight twist of the torso. The Spanish artist is seen here as completing the process, begun by Tiepolo, of changing the way we read a painting – forcing the viewer no longer to rely on visual clues, but to meet the painting on its own terms – and thereby anticipating modernity.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?