Including digital projections of William Blake’s unrealised frescoes and a restaging of the disastrous exhibition he held above his brother’s hosiery shop in 1809, this comprehensive show looks beyond the Romantic artist’s famous illustrated manuscripts to reassess his grander ambitions as a painter. Find out more from the Tate’s website.

Preview the exhibition below | View Apollo’s Art Diary here

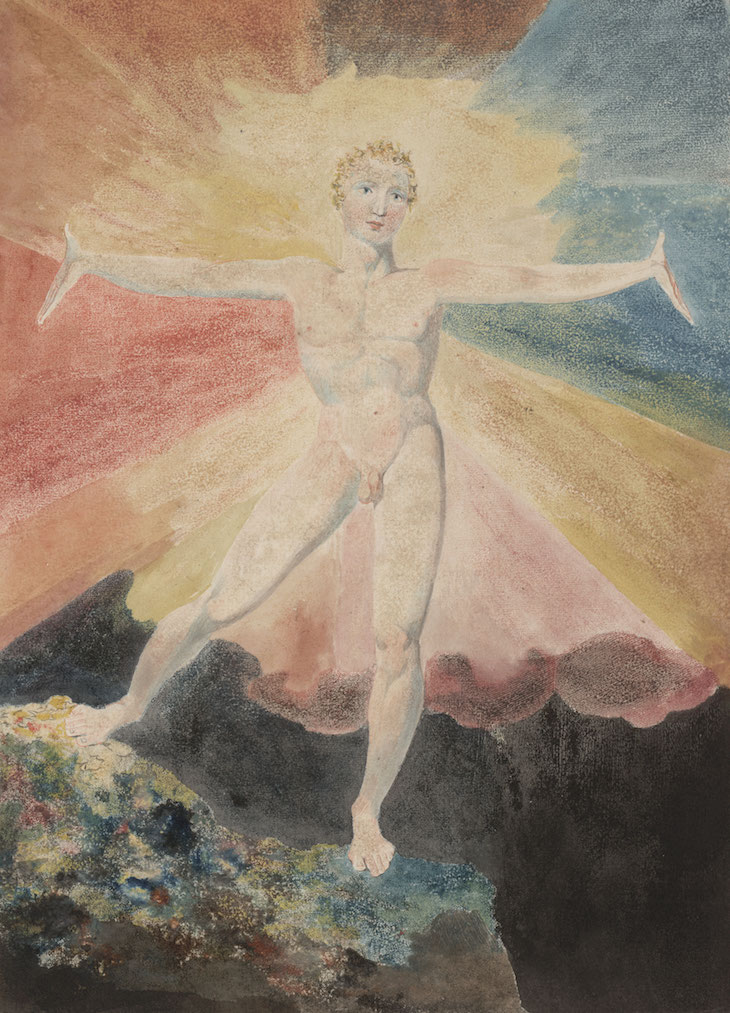

Albion Rose (c. 1793), William Blake. Courtesy Huntington Art Collections

At the heart of the elaborate and idiosyncratic mythology that governs Blake’s poems and paintings stands Albion – the mythic name for Britain, but also a primeval, perfect entity who fell from heaven at the beginning of human history, dividing into four spirits that Blake called ‘Zoas’. In this early painting, Albion stands triumphant, restored by God to utopian grace – an allegory for what Blake envisioned, in the wake of American independence and revolution in France, as Britain’s future political liberty.

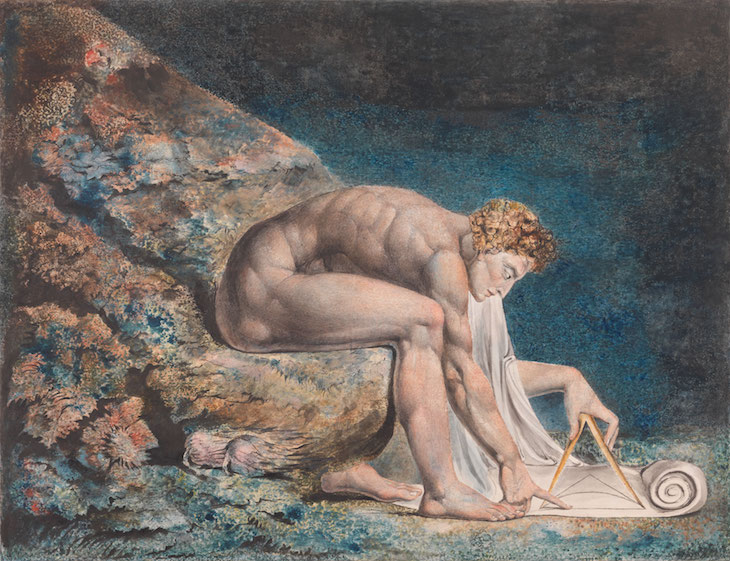

Newton (1795–c. 1805), William Blake. Tate Collection

‘Reason says “Miracle”: Newton says “Doubt”’, Blake wrote cryptically but scathingly of Isaac Newton in ‘You don’t believe’. Throughout his life Blake deplored the slavish adherence to the evidence of the senses that he believed had been ushered in by Newton and other scientists of the Enlightenment; in this famous work he shows Newton’s attention fixed to his compass, realising neither that he appears to be submerged underwater, nor the miraculous beauty of the coral on which he perches.

Ghost of a Flea (c. 1819), William Blake. Tate Collection

Blake’s fearsome depiction of bloodlust was the result of a séance in 1819, during which the spirit of a flea explained to the artist that all of its kind was possessed by men who were ‘by nature bloodthirsty to excess’. Blake’s anthropomorphic beast is shown here transfixed by the bloody goblet it appears to have just drained.

‘Europe’ Plate i: Frontispiece, ‘The Ancient of Days’ (1827), William Blake. Whitworth Art Gallery, University of Manchester

Urizen, one of the four Zoas, brings the earth into being with his vast compass. Circumscribed here by the heavenly orb in which he crouches, he at once creates and constrains; Blake thought of him as the embodiment of reason, law-making and repression, worshipped blindly by his empirically minded contemporaries. This engraving was used as the frontispiece to Europe: A Prophecy – a rhapsodic poem, one of Blake’s ‘illuminated manuscripts’, in which Urizen’s agents are pitted against Orc, the spirit of wild rebellion and revolutionary energy.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?