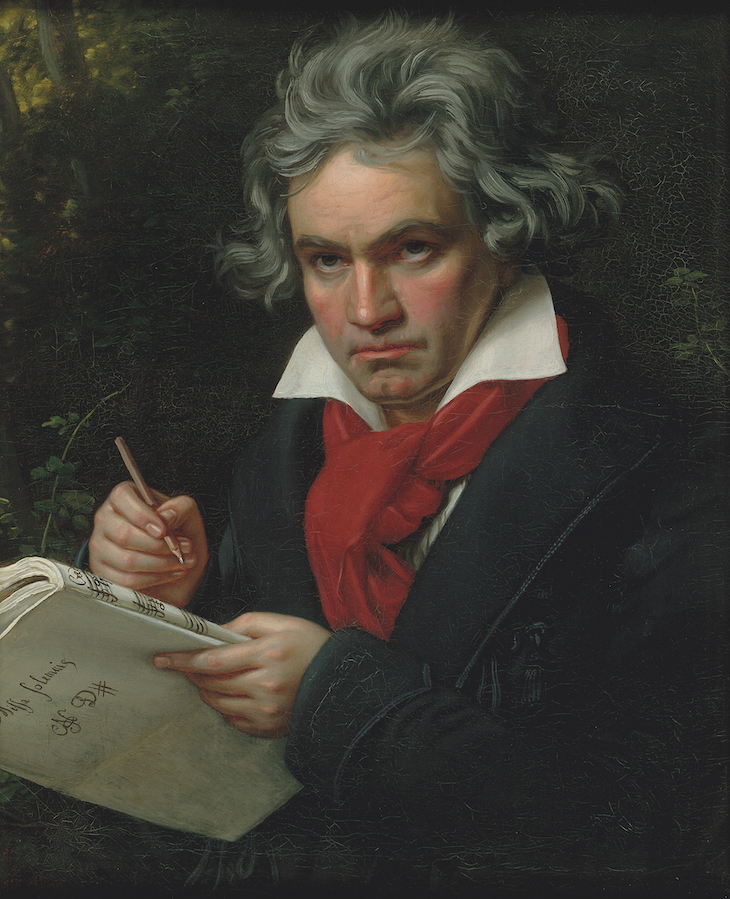

Between February and April 1820, Joseph Karl Stieler, court artist to the Bavarian kings, created what remains the most famous portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven. For two centuries, it has perpetuated the popular image of the composer – his brooding demeanour and his reputation as a lover, and force, of nature. Illuminated in a forest setting, Beethoven looks into the distance as he awaits inspiration for his Missa Solemnis, the score clasped in his left hand.

While the painting, its reception and its influence on later artists are currently the subject of a bicentenary exhibition at the Beethoven-Haus in Bonn, less well known is its at times turbulent history as a material artefact – the way in which it has become something like a holy relic for those who have owned it, and its entanglement in the story of Nazi appropriation of art and aesthetics during the Third Reich.

Stieler claimed that he was the only painter for whom the notoriously edgy Beethoven had agreed to pose. He rarely, if ever, agreed to such sittings, considering them a kind of penance. On this occasion he agreed, mainly to honour the wish of his patrons and ‘best friends in the world’, Franz and Antonie Brentano, that Stieler paint him. (Antonie has been suggested by some musicologists as the most likely intended recipient for the composer’s impassioned, and undelivered, ‘Immortal Beloved’ letter.) Beethoven, though, was unable to stay still past the four sittings and Stieler was left to paint the hands from memory.

Beethoven with the manuscript for Missa Solemnis (1820), Joseph Karl Stieler. Photo: © Beethoven-Haus Bonn

After being well received at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, the portrait was acquired by Wilhelm Spohr, brother of the composer Louis Spohr, in a raffle at the Art Association of Brunswick. Following Wilhelm’s death in 1860, it was inherited by his daughter Rosalie, Countess Sauerma, a celebrated harpist. It seems that for those involved in the world of music, the only portrait of Beethoven painted from life held a special appeal.

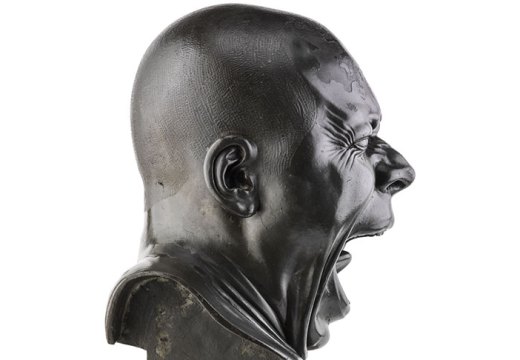

And so, on 10 February 1909, Henri Hinrichsen, proprietor of the music publisher C.F. Peters, acquired the portrait from the Countess. Pride of place was given to it in his private music room and a small number of copies were made for close friends. ‘I am very, very proud to have this excellent reproduction, which is otherwise not obtainable,’ wrote the composer Max Reger, who hung it alongside prized death masks of Brahms and Wagner, and a splinter from Beethoven’s coffin.

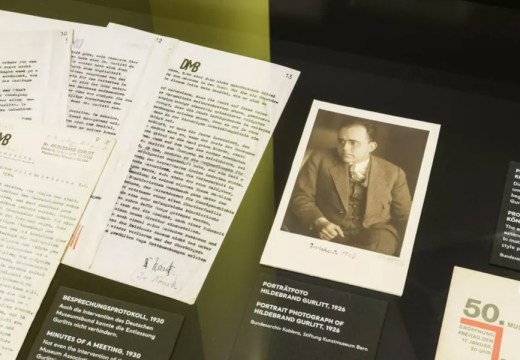

Hinrichsen was a prominent figure among Leipzig’s Jewish community which, before the rise of National Socialism, numbered around 11,000. Because of Hinrichsen’s status as a generous cultural benefactor to the city, and the fact that he avoided publishing ‘degenerate’, avant-garde works, he initially managed to keep his family and his business relatively safe. On Kristallnacht in November 1938, however, while Hinrichsen and his wife Martha were away in Vienna, his home and offices were looted. The company was confiscated and ‘aryanised’ the following year. Hinrichsen was also forced to part with his collection, made up primarily of 19th-century German paintings. Two paintings and drawings were sold to the art dealer and war profiteer Hildebrand Gurlitt, but Hinrichsen never received any money as all of his accounts were frozen.

For the Nazis, German music – particularly Beethoven’s and Wagner’s – was considered to be foundational to the ‘thousand-year Reich’. Notwithstanding the ambiguity of Beethoven’s own political views, the Nazi musicologist Arnold Schering interpreted the Fifth Symphony as a ‘fight for existence waged by a Volk that looks for its Führer and finally finds it’. The seizure of Hinrichsen’s prized portrait of the composer must have been especially satisfying. ‘There is only one Beethoven-Stieler portrait. That was mine,’ Hinrichsen wrote to his son Walter, who had emigrated to the US to set up an American branch of C.F. Peters.

Eventually, Hinrichsen was arrested in Brussels in September 1942. He died in the gas chambers of Auschwitz-Birkenau at the age of 74. After the war, Walter – by then a sergeant in the US army, appointed as Music Officer in the Control Commission in Berlin – returned to Leipzig, to secure back the family firm. Shortly before the withdrawal of American troops, he briefly regained ownership of the company; after the city was turned over to the Red Army, it was once again confiscated, later to be established as a state-owned business in the new German Democratic Republic. He was, however, able to negotiate the permanent return of some of his father’s collection. The Beethoven portrait was shipped to New York where it hung in Walter Hinrichsen’s office at the C.F. Peters Corporation. In 1981, a copy was made and the original was sold to the Beethoven-Haus.

From countless engravings to a portfolio of screenprints in 1987 by Andy Warhol, Stieler’s painting is the image upon which depictions of Beethoven have been based ever since. After a long journey, it now hangs in a place with its own very tangible connection to the composer – the house where he was born, 250 years ago.

‘In good company: Joseph Stieler’s Beethoven portrait and its history’ is at the Beethoven-Haus Bonn until 26 April.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?