From the April 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Jan Morris was no fan of Venetian cooking. Its mood was one of ‘lofty frugality’, she wrote in Venice (1960), complaining of the ‘soporific sameness’ of the restaurants and trattorie of the city. There was some succour to be had from coarser fare: ‘It is only when you come to the fish, the native food of the Venetians, that you may feel a spark of enthusiasm […] the lower you slither in the hierarchy of the Venetian kitchen, the more you are likely to enjoy yourself.’

The Italian painter Cagnaccio di San Pietro (Natalino Bentivoglio Scarpa; 1897–1946) would have sympathised, I think, even if more by necessity than choice. Born in Desenzano, on the shores of Lake Garda, Cagnaccio grew up in the Venetian fishing village of San Pietro in Volta – where his father was a lighthouse keeper – and would live there until moving to Venice in the early 1930s. Even at his house near the Zattere, and for all his appearances at Caffè Florian or Bergamin, his never became a life of plenitude: in 1937, suffering ill health and penury, the artist described how his body had ‘deteriorated to become a carcass’.

In his work Cagnaccio made the ragged fringes of La Serenissima his own. By 1919, having abandoned formal artistic training after a year, he took on the moniker that would tether him to the fishing community of his childhood for good (‘Cagnaccio’, wild dog, had long been a family nickname, thanks to an unruly pet owned by the artist’s grandfather). In portraits and tableau paintings he began to depict fishermen and their families with a realism akin to that of his German contemporaries of the Neue Sachlichkeit: as disquieting in its directness, certainly, albeit with more sympathy for his subjects. His scrupulously observed still lifes, usually painted on cheap board, transformed the familiar harvest of the lagoon – a lobster, a dogfish, a spider crab – into objects of wonder or veneration.

Cagnaccio painted what he knew, then, and also what was to hand: as illness pushed him into confinement in the 1930s, his still-life production increased by force of circumstance. Asceticism bred attentiveness. A Cagnaccio still life depicts only a few objects, meticulously arranged on table linen so as to engender uncertain relationships between them. In Natura morta con granceola (‘Still Life with Spider Crab’; 1939), for instance, the crab sits on a white plate with a single lemon before its claws, like a child posing with a toy ball. Yet the painting offers a gently elevated perspective, perhaps hinting at a diner’s viewpoint, so that the lemon might be more condiment to, than attribute of, the crab. In Natura morta con aragosta e rapanelli (‘Still Life with Lobster and Radishes’; 1938), the affinity between objects is at once tonal (reds, pinks, oranges) and formal, with the array of radish greens reprising the tail fan of the lobster. But this strange, spartan juxtaposition also suggests a ritualistic meal, even a private eucharist: from 1940 the increasingly devout Cagnaccio would add the initials S.D.G., ‘Soli Deo Gloria’, to his signature.

Cagnaccio was always an outsider, for all that he is now often designated a ‘magic realist’ alongside Felice Casorati, Antonio Donghi and others. In his lifetime he never allied himself to artistic movements. Although he showed work at the Venice Biennale from 1924, he was largely shunned by the artistic establishment due to an incorruptible anti-fascism that led to his exclusion from the exhibition in 1928. But it was also his style that made him an interloper in Venice at the time: a fastidious realism that seemed archaic, on the one hand, but a world apart from the sprezzatura of the great Venetian tradition on the other. In 1935 the art critic Ugo Ojetti chastised Cagnaccio as a ‘relentless draughtsman […] who knows too much about the other side of the Alps when it comes to sharp outlines and shiny colours’.

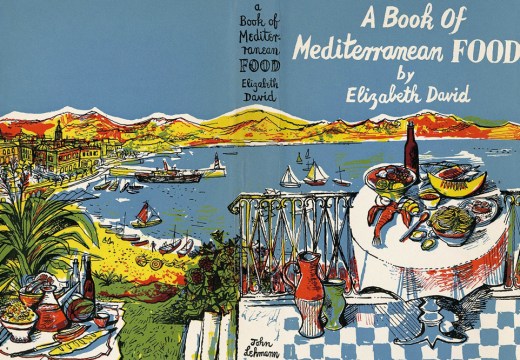

Well, perhaps. Later critics have drawn parallels between Cagnaccio’s crystalline paintings and the crisp linearity of the Venetian quattrocento, that of Crivelli and Bartolomeo Vivarini. But might Cagnaccio’s vision not have been more simply honest to the objects that he observed and the city in which he knew them? In Italian Food (1954), Elizabeth David described the fish market near the Rialto as ‘the most remarkable’ in Italy: ‘The light of a Venetian dawn in early summer,’ she wrote, ‘is so limpid and so still that it makes every separate vegetable and fruit and fish luminous with a life of its own, with unnaturally heightened colours and clear stencilled outlines.’ She could have been describing a still life by Cagnaccio. His aubergines and peppers catch the light like Murano glass. His bread rolls are little baroque sculptures. And the crustaceans look almost too good to eat, demanding instead to be painted.

From the April 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?