The South London Gallery’s new annexe is a building with a varied history. It was once the headquarters of butchery business Kennedy’s, a sign still visible on the exterior of the building next door. Before that, it was a purpose-built fire station – the oldest that remains standing in the city. Despite this heritage, the station stood derelict until 2014, when an anonymous benefactor donated it to the SLG. Now it has been transformed by 6a Architects, a firm whose proficiency in converting period properties into contemporary art galleries was cemented with the success of Raven Row in Spitalfields in 2009. For this project a similar approach has been taken to preserve original features, from the floorboards and industrial doors to a lantern inscribed with a sign reading ‘Engines’.

While the SLG’s main site displays all the grandeur of a municipal public gallery, the Fire Station feels more intimate, which is not to say it fails to impress. Visitors are greeted by a double-height foyer, complete with original brickwork and the charred remnants of a fireplace floating high up on the wall. On each of the four floors there are small galleries, nearly all of which are currently occupied by ‘Knock Knock’, the inaugural exhibition co-conceived by the institution’s director Margot Heller and artist Ryan Gander as an exploration of comedy in contemporary art.

Peckham Road Fire Station, 1905. London Metropolitan Archives, City of London/Collage: The London Picture Archive

No space of the building is spared: Judith Hopf’s Flock of Sheep (2013), a forlorn group of concrete blocks on metal legs, appears hidden under the newly installed steel staircase. Meanwhile, one of Yonatan Vinitsky’s cartoons – of two men holding a pane of glass – hugs the wall space above the stairs. The image is constructed from lines of black elastic pulled taught with nails, only becoming properly legible when you view it looking down from the upper floors.

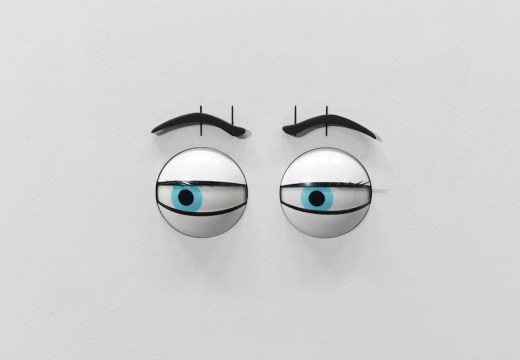

Joking around is an undeniably difficult subject to convey in an exhibition, and the silence that follows a failed punchline must have been a serious concern. It seems, however, that ‘funny, ha ha’ is not the desired response in this show, which tends towards expressions of dark humour. No one could mistake Ugo Rondinone’s sleepy clown for an upbeat affair, and Jamie Isenstein’s sculptures formed from layers of cartoon masks are more horror than hilarity. Similarly, the shrill screeches that emanate from Lucy Gunning’s film The Horse Impressionists (1994) filled me with dread even after discovering that their source lies in women imitating equine communications. They might be laughing, but their high-pitched whinnies are enough to make your blood run cold.

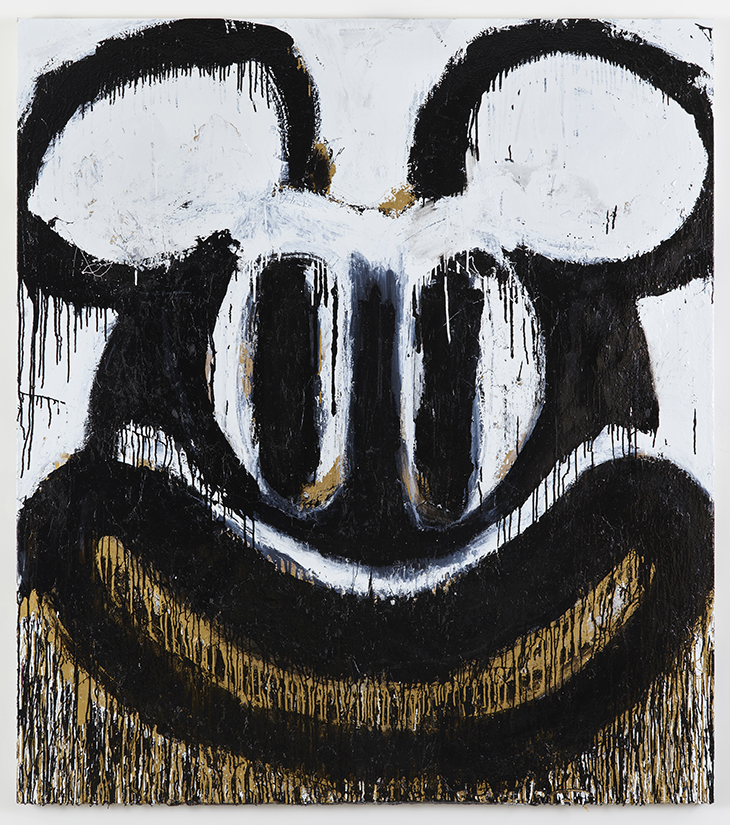

Black and White Mickey (2018), Joyce Pensato. Courtesy Lisson Gallery; © Joyce Pensato

Elsewhere, the use of humour as the show’s unifying thread seems to unwittingly diminish the impact of works on display. Harold Offeh’s video from 2001, Smile, seems somewhat misread: the artist’s fixed grin, obeying the instructions of the Charlie Chaplin song of the same name (here sung by Nat King Cole), hints at suppressed sorrow and the endurance of suffering.

The show continues in the main site, where a sinister spectre also looms. Bedwyr Williams’ sculpture of a bicycle covered in fur with a ram’s skull for handlebars looks like the forgotten remnants of a Burning Man vehicle, though the title Fucking Inbred Welsh Sheepshagger (2018) might induce a snicker from some viewers. Joyce Pensato’s demonic Mickey Mouse drawings are like something from a nightmare, and Ceal Floyer’s interpretation of the classic saw-in-the-floor joke comes across as more Shallow Grave than slapstick. A highlight is a compelling video from Pilvi Takala titled Real Snow White (2009), which shows the artist in an altercation with Disneyland staff, recorded on a hidden camera, as she tries to enter the amusement park while wearing a costume of the animated princess.

Real Snow White (film still; 2009), Pilvi Takala. Courtesy the artist, Carlos/Ishikawa London

As security guards explain the complex reasons why an adult cannot imitate fairytale characters within their jurisdiction, Takala is mobbed by children seeking photos and autographs. Her crestfallen manner throughout the heated discussion is both charming and heartbreaking. It one of more successful pieces in the show, as it navigates the extremes of unbridled joy and disappointment that characterise childhood experience. As Takala is exiled to a public toilet to get changed, her army of fans grows, and the sight of Snow White being frog-marched by security as children wail is the surely the saddest joke of them all.

‘Knock Knock: Humour in Contemporary Art’ is at South London Gallery, until 18 November.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?