As Christopher de Hamel points out in the introduction to this beguiling book, nearly anyone ‘with stamina and a travel budget’ can take in the masterpieces of world architecture, sculpture or painting. And, what’s more, you can experience such masterpieces, more or less, as they were originally experienced. But manuscripts are a different matter. Even a dedicated museum-goer is unlikely to see many of them: most lie deep in library stores, available only to researchers; and the rare few on display remain constrained under glass, open at a single spread. For most people, the possibility of holding and handling such a manuscript as its original readers might have done is so remote as to be laughable. ‘It is easier,’ as de Hamel puts it, ‘to meet the Pope or the President of the United States than it is to touch the Très Riches Heures of the Duc de Berry.’

There are, of course, surrogates available – print facsimiles and the digital scans increasingly available for free online – but nothing can stand in for what de Hamel calls ‘meeting’ a manuscript. It’s not just that no reproduction yet invented can recreate ‘the weight, texture, […] thickness, smell […] of an actual medieval book’; to de Hamel every manuscript is an object with its own personality and life history. The conceit of Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts is that he is acting as a kind of celebrity interviewer. His role, as he presents it, is to enter into conversation with his chosen manuscripts, enquire into their origins, meanings and life histories, tease out insights and even, as it were, to go through the keyhole to ‘document their habitat’ in the rare book repositories of the world.

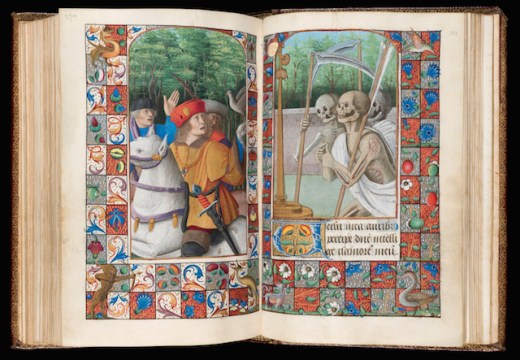

Page from the Spinola Hours, showing Christ carrying the Cross, c. 1515–20, Flemish. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

In the wrong hands that conceit could easily prove irritating, but de Hamel is the living definition of a genial and expert guide. He has lived and breathed palaeography since discovering as a teenage New Zealander the ‘modest but absolutely real medieval manuscripts’ of Dunedin Public Library, going on to spend 25 years in the Western Manuscripts Department at Sotheby’s, before becoming the custodian of the enviable collection at Corpus Christi College in Cambridge. What de Hamel doesn’t know about manuscripts wouldn’t, I suspect, be much worth knowing. Just as importantly, he is also an infectious enthusiast. Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts is a deeply scholarly book, but fundamentally it’s all about sharing the pleasure of manuscript studies – bibliophilia in the truest sense. ‘Of course,’ he admits, ‘I am the most biased person in the world, but I think that medieval manuscripts are truly fascinating at so many levels.’ And as he starts peeling away the layers, it’s easy to share his desire to ‘know everything’ about every book: from the details of their production and use, to their often extraordinary journeys through history, to the voyeuristic thrill of ‘poking impertinently into the affairs of men and women of long ago’.

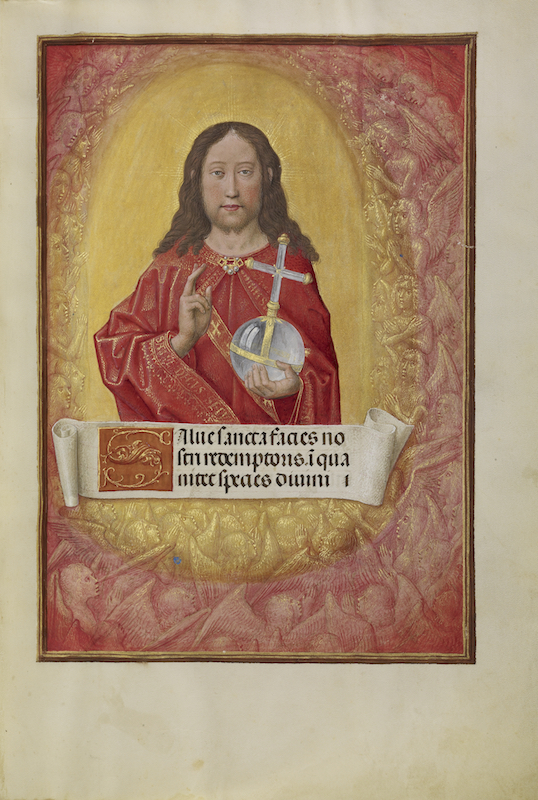

Page from the Spinola Hours, showing Christ resurrected in Heaven, c. 1515–20, Flemish. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

The dozen manuscripts de Hamel chooses for interview come from the upper echelons of the manuscript world, but they also cover a lot of ground. Temporally, de Hamel’s picks span the late sixth century right up to the early 16th – well into the era of printed books. In subject, they run from the expected biblical texts and prayer books, through to astrology, military tactics, and drinking songs. And in appearance, they take in both the dazzling and the drab – the Hengwrt Chaucer (c. 1400), despite its status as a world treasure, is not a visual feast. The selection is aimed at being representative (and it is), but, really, de Hamel’s central criteria are glamour and interest – what he terms ‘a bit of self-indulgent namedropping’. These are books that, aside from their intrinsic beauty, reveal extraordinary things about the history of early Christianity, classical scholarship, and the history of reading. And their stories are buoyed up even further by some provenances that, between bishops, monarchs, revolutionaries, Nazis, and several outrageously cupidinous book collectors, could have been cribbed for an Indiana Jones sequel.

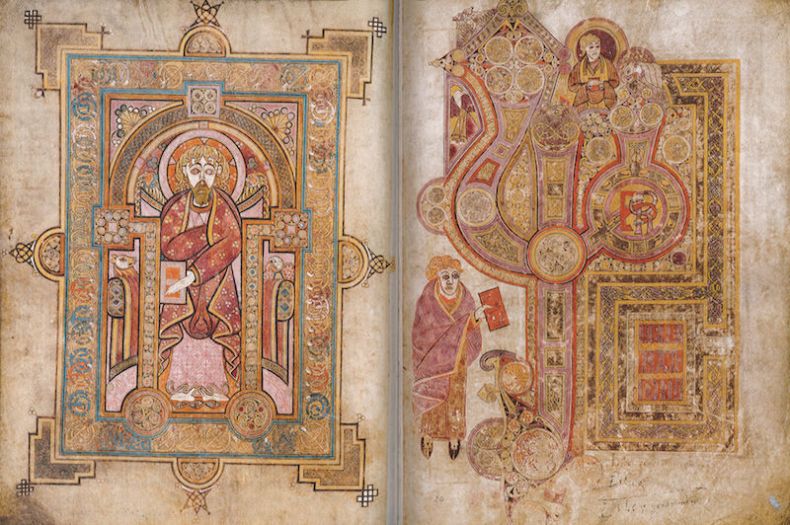

As Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts is entirely sui generis, it is worth taking a moment to say what it is not. While lavishly illustrated, it is by no means a coffee-table book, and it is not primarily about the illuminations or glorious miniatures that grace its most spectacular choices, the Book of Kells and the Spinola Hours. De Hamel’s real interest and expertise lie in palaeography: understanding how and why manuscripts were put together, mining the meanest technical detail for unexpected aperçus about culture and history. He is as wowed by the evidently exciting things as anyone else – and writes beautifully about them – but at heart, he is a detail man, deciphering the clues to be found in manuscript collations, materials, scribal hands. Several chapters here could, in fact, best be described as performance palaeography, with de Hamel using his physical examinations of the books to test old hypotheses and offer new ones. Chaucer scholars will need to take note of his examination of Linne Mooney’s theories about Chaucer and his possible scribe ‘Adam’; a more rarefied audience still will be poring over his reconstruction of a deleted phrase in the Copenhagen Psalter from a few remaining scraps of ascender.

The beginning of Matthew’s Gospel from the Book of Kells showing Matthew (left) and Book of the Generation (right), late 8th century, Irish. Trinity College, Dublin. © The Board of Trinity College, Dublin

To dwell on de Hamel’s scholarship runs the risk of making this sound like a dull book for a specialist audience. That it emphatically is not. De Hamel tells the lives of his manuscripts with verve and unfolds his judgements with style. It is both fascinating and, in its engagingly donnish way, very funny. He is particularly good on the idiosyncrasies of rare books rooms across the globe – everywhere has its own rules, often inscrutable, and everywhere tends to be patronising about one’s ignorance of them. His encounters with rare books rooms and their staff in New York (‘Ripples of disapproval’) and St Petersburg (being brought ‘whisky-flavoured Russian chocolates to eat at my desk’) form comic set-pieces that made me laugh out loud more than once. While I too would tend to be biased about the inherent fascination of medieval manuscripts, it takes a rare writer to make palaeography this interesting. It is a gem of a book.

From the January issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?