The wristwatch in Domenico Gnoli’s 1969 painting of the same name barely registers – a mere sliver in the shape of a crescent moon, in the bottom left-hand corner. Covering the face of the watch, and dominating the work, is the sleeve of a grey chevron-patterned suit jacket; it rests against the garment’s front panel, creating two planes of delicate zigzags, one horizontal and the other at a slight angle.

At first, the tightly cropped, close-up painting of a besuited man’s forearm appears straightforward. But the longer you look, the more the enlarged details – the three buttons on the sleeve, the slender pocket opening, the grainy texture created by mixing acrylic with sand, and the never-ending zigzags with their slight imperfections – acquire a hypnotic aura. The magnetism of the fragment amplifies the lost whole, forcing the viewer to confront the lack of context and perhaps even reconstruct it, not unlike an archaeologist unearthing a pottery shard.

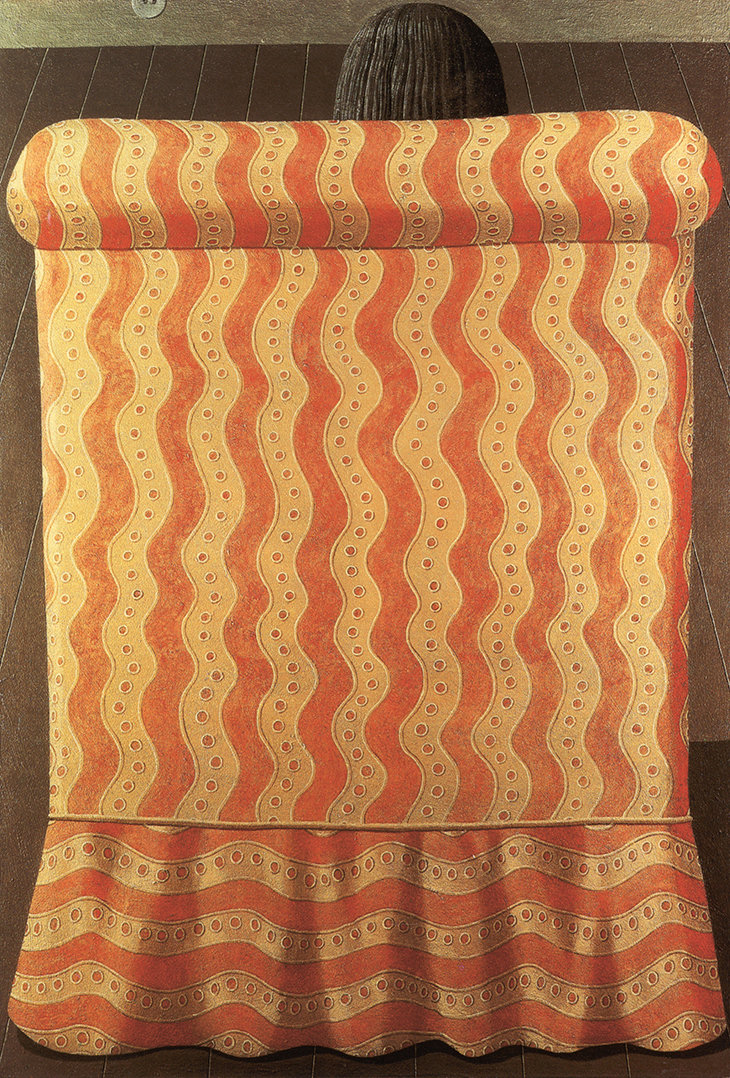

Fauteuil N° 2 (1967), Domenico Gnoli. Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Image: © Domenico Gnoli, SIAE/DACS, London 2022

Gnoli (1933–70) is best known for these paintings, in which he explores a new reality by isolating details from everyday life. They serve as the centrepiece of Fondazione Prada’s retrospective ‘Domenico Gnoli’. And rightfully so: begun in 1964, six years before the artist’s untimely death, this line of work represents a shift from the narrative illustrations and set designs that had been his bread and butter. As the Italian archaeologist and art historian Salvatore Settis puts it in his essay in a book accompanying the exhibition, Gnoli developed ‘a painting idiom all his own’.

Split between two levels, the exhibition opens with more than 70 of Gnoli’s paintings on the first floor, grouped according to subject matter. There’s an entire wall of shoes, for instance, and another with torsos and the outlines of bodies in bed, hidden under patterned blankets. Almost all are large-scale, with a sharp focus and photographic framing. Even those that offer a wider perspective – L’ascenseur (1967) shows an empty elevator in the fading light, and Tavoli di ristorante (1966) features restaurant tables draped in white linen yet devoid of place settings – tend to portray a suspended reality, one often characterised by absence. There’s always something just out of frame at which the viewer can only guess.

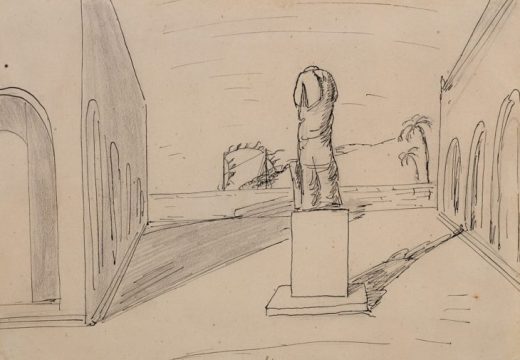

Maquette (1967), Domenico Gnoli. Private collection. Image: © Domenico Gnoli, SIAE/DACS, London 2022

The effect of this assembly of Gnoli’s paintings is not a bit melancholic, in part because of the absence inherent in these works but more so because the immense talent on display makes you wonder what he could have achieved if his blossoming career hadn’t been cut short. (Another absence should also be noted: the curator and art critic Germano Celant, who was the driving force behind the exhibition, passed away in April 2020 from coronavirus complications.)

Taken alone, such a comprehensive collection of the artist’s paintings is itself noteworthy. Yet in true retrospective form, the second half of the show fills out Gnoli’s artistic endeavours, showcasing his accomplishments as a set designer and an illustrator. The child of a ceramicist and art historian, Gnoli embraced drawing and painting early on. He first made a splash in 1955, when, at the age of 22, he designed the sets and costumes for William Shakespeare’s As You Like It at the Old Vic in London. From 1959, he lived between Paris, London, Rome and New York, where he worked as an illustrator for magazines and other publications. An abundance of archival material, including drawings, sketches, books, exhibition catalogues and murals, traces his unique trajectory.

After the eerily silent detail on the first floor, it’s invigorating to see so much action, both depicted and implied – what Gnoli called ‘decoration’. In many of his imaginative drawings, people are packed into every nook and cranny. In one of his illustrations for Richard Austin Smith’s article ‘Cape Canaveral, Industry’s Trial by Fire’ (Fortune, June 6, 1962), reporters and cameramen are crammed onto a field in the lead up to a rocket launch. In a drawing for Waverley Root’s The Cooking of Italy (New York, 1968), he depicts a bustling market in ancient Rome.

People are to the fore in Gnoli’s theatre designs as well. While he builds an inspired world for the actors on stage, he’s also concerned with the observer – the humanity off stage, much like the humanity out of frame in his paintings – as evidenced by his drawings of spectators at the Apollo Theatre (1962) and in his set design model for The Lily of Toledo Ballet (c. 1957–58), a bullring where the audience members are more captivating than the location. As the artist wrote in a letter to Ted Riley, ‘an audience is perhaps unnecessary to the soulsearching mystic, but it is vital to the magician, the maker of prodigies.’

With his set designs and illustrations as the starting point, the route to his final destination – if Gnoli’s paintings can be called that – becomes clear. While the subject matter of the fresco-like La taverne (1963) is similar to his narrative illustrations, it has the graininess, made by mixing paint (oil, tempera, acrylic) with glue and sand, that became a defining element of his painting practice. Moreover, the artist’s ‘bestiary’ illustrations build on some of the objects he painted, embellishing them with fantastical beasts: a whinged rhino taking a nap in an elevator, for instance, and a snail lounging on a sofa.

Winding back through the first portion of the show – which is the only way to exit – brings a new appreciation for the mix of distance and intimacy, the interplay between fantasy and reality, that embodies Gnoli’s work. At its core, his art draws the viewer’s attention to the sensuality and carnal theatre of everyday life. And in that way, it doesn’t fit neatly within a particular style. While his paintings can be understood in relation to Pop art, he merely crossed paths with the movement rather than seeking a home there. Likewise with the other labels often applied to his work, from minimalism to hyperrealism, abstraction to Surrealism – he learned from but never fully assimilated these artistic languages.

As Gnoli himself explained in an interview with JeanLuc Daval for Le Journal de Genève, ‘My themes come from the world around me, familiar situations, everyday life; because I never actively mediate against the object, I experience the magic of its presence.’ As opposed to Pop’s celebration of consumer culture, his paintings illuminate the objects in question. And while they can border on abstraction – it’s easy to become so engrossed in a stitch, a pattern, or even a colour that you almost forget what you’re looking at – his paintings revere the mundane, which is charged with a life force just outside of view.

‘Domenico Gnoli’ is at the Fondazione Prada, Milan, until 27 February 2022.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam got its rehang right?