From the April 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

‘Had any one ever seen such doings?’ complains uncle Baudu, the proprietor of an old-fashioned and dingy shop, near the start of Emile Zola’s novel Au Bonheur des Dames (The Ladies’ Paradise; 1883). ‘A draper’s shop selling everything! Why not call it a bazaar at once?’

The object of Baudu’s ire, across the street from his dark and damp establishment, is a modern department store; it blazes with gaslight, and its large windows are piled with everything desirable. He is witnessing the end of his draper’s business, supplanted by the shining palace opposite, and obviously he hates it, its fripperies, its clientele and its young, perky staff: ‘No affection, no morals, no taste!’

Today, it’s department stores that are dying, their embattled business model dealt a savage blow by the coronavirus pandemic. Jenners, a landmark on Edinburgh’s Princes Street for 183 years, announced its closure in January. Debenhams is closing all its remaining branches. House of Fraser, which operated many regional department stores including Jenners, collapsed in 2018, and its remaining stores are now under severe pressure.

Most department stores originated from drapers’ businesses. Though they are now associated with premium shopping, they were at first regarded as places for cut-price luxury, exploiting the economies of scale made possible by improved manufacturing, transport and construction. This gives them an air of technological inevitability, and helps explain why their origins are so contested, claimed by several establishments in several places and several times. Whatever their ancestry, the spiritual birthplace of the department store was the Great Exhibition of 1851. There was the template: vast spaces and incomprehensible abundance, enclosed in a diaphanous modern construction of iron and glass.

William Whiteley, who founded Whiteleys in Bayswater in 1863, was explicitly inspired by the Exhibition. ‘As a youth enchanted with the Crystal Palace, he had been struck by the tantalising way that goods were available to the eye but remained ultimately unattainable,’ writes the historian Erika Rappaport – as much as retail, Whiteley’s was situated in ‘London’s emerging culture of spectacle and display’.

Zola drew his inspiration from Le Bon Marché, Paris’s first department store. The name he chose for his novel attests to the earliest public image of the department store: it was a place for women, and a liberating one. With its comforts and amenities and its public yet private spaces, it eased the path of the middle-class woman into the life of the city. It also employed young women, and on both counts attracted the judgement of the Baudus of the world. As Rappaport relates, Whiteley was attacked for not simply selling to women but also letting them linger and serving them refreshments. At Jenners, the importance of women to the business was carved into the stone of its Princes Street store, the upper stories of which are decorated all around by caryatids.

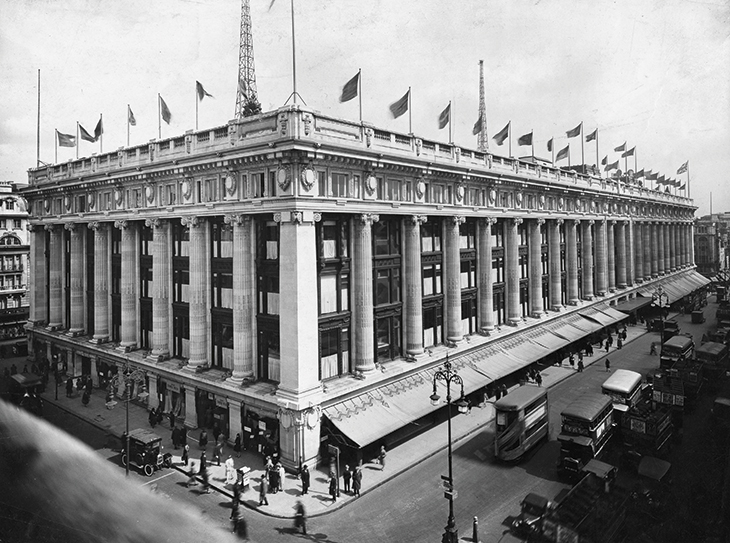

Selfridges on Oxford Street, London, designed by Daniel Burnham with later additions by R.F. Atkinson and T.S. Tait of Sir John Burnet & Son and photographed in 1929 by Sydney W. Newbury. Photo: Riba Collections

The baroque extravagance of William Hamilton Beattie’s building for Jenners shows the opulence and grandeur with which the department store clad itself, but extravagance did not mean archaism. They were the successors of the arcades that Walter Benjamin called ‘the hollow mould from which the image of “modernity” was cast’. Department stores were at the spearhead of architectural innovation. Halfway through Zola’s novel, the store moves to larger premises. The new building epitomises modern construction and ideas: ‘The architect, who happened to be a young man of talent, with modern ideas, had only used stone for the basement and corner work, employing iron for all the rest of the huge carcass […] Space had been gained everywhere; light and air entered freely, and the public circulated with the greatest ease under the bold flights of the far-stretching girders. It was the cathedral of modern commerce, light but strong, the very thing for a nation of customers.’

This was not true only at the start of their history. Selfridges’ Oxford Street flagship, which opened in 1909, was designed by the American architect Daniel Burnham: a transatlantic Beaux-Arts palace wrapped around one of Britain’s earliest steel frames. Peter Jones on Sloane Square, designed by William Crabtree and completed in 1936, was the country’s first modern curtain-wall building. In 1920s Germany, Erich Mendelsohn designed a succession of astonishingly modern curved-glass stores for the Schocken chain before both architect and client were driven out by the Nazis. In the first years of the 21st century, Selfridges made an effort to recapture some of this adventurous spirit with its Birmingham store, a shining blob designed by Future Systems.

The Schocken department store in Stuttgart, designed by Erich Mendelsohn and photographed in 1928, the year it opened, by Francis Rowland Yerbury. Photo: Riba Collections

But the historian Wolfgang Schivelbusch notes that the iron and glass architecture of the 19th century embodies a paradox: just as construction techniques made it easier to fill capacious interiors with daylight, reliable sources of artificial light made natural light less important. The wide windows of department stores were more useful for bringing in customers than daylight – they were filled with displays. Large interiors, without external points of reference, could feel labyrinthine. Boswells, the local department store in my childhood home city of Oxford, had a basement toy department that will live forever in my dreams as an Aladdin’s cave, but the rest of the store was confusing, old-fashioned and (in my mind at least) entirely interior – I had to visit it on Google Street View to remind myself that it even had a street frontage, let alone what it looked like. Boswells closed for the last time in 2020.

The department store had already acquired a fusty, forbidding aura when the British sitcom Are You Being Served? was first aired, and that was half a century ago, in 1972. Nevertheless, it was still able to innovate, serving as the ‘anchor’ of that 20th-century retail paradise, the shopping mall. (In her essay on malls, Joan Didion notes that they were rated according to the size and prestige of the department store they could attract.) Now many of those anchor stores are challenged. Meanwhile cities must find new uses for redundant stores. Jenners and Boswells are doomed to become luxury hotels, but the former Debenhams on Oxford Street may become an art gallery. And in Burlington, Vermont, a mall department store has been converted into a temporary high school. If the high street and the city centre are to survive, these important landmarks must find new ways to become destinations. Otherwise the city may succumb to the 21st century’s version of retail modernity: the cavernous, windowless, invisible, under-regulated, under-taxed Amazon warehouse. Are you being servered?

From the April 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam got its rehang right?