Alice Neel: People Come First

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

22 March–1 August

It’s hard to imagine there was a time when the hurrahs and plaudits that greeted ‘Alice Neel: People Come First’ at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York earlier this year would have come as a surprise to gallery-goers. Neel (1900–84) spent much of her life struggling to get on and to get by. She lost an infant daughter to diphtheria, attempted suicide more than once, was institutionalised, had hundreds of her canvases slashed by a jealous lover. Even when, in 1974, she was finally afforded a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the New York Times critic Hilton Kramer sniffed that she was ‘not the kind of artist whose work can sustain such scrutiny’.

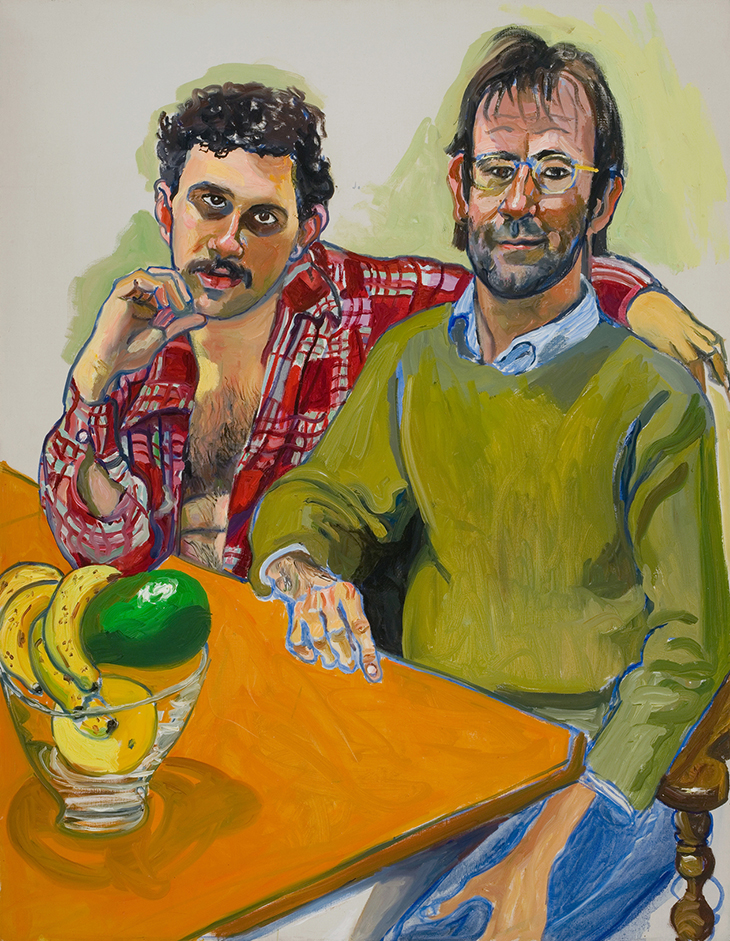

This exhibition, curated by Kelly Baum and Randall Griffey, made a nonsense of that assessment. People tumbled out of the show’s hundred-odd paintings, drawings and watercolours: the defiant protestors and placard-wavers in Nazis Murder Jews (1936) and Save Willie McGee (c. 1950); the motley new migrants from the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico whom Neel saw thronging the streets and fish markets of Spanish Harlem, where she herself lived for much of her life; lovers, agitators, poets, art-world dignitaries both famous and forgotten. No wonder she disliked the idea of ‘portraits’: she thought the term too static and stuffy, preferring instead ‘pictures of people’.

Jackie Curtis and Ritta Redd (1970), Alice Neel. Cleveland Museum of Art. © The Estate of Alice Neel

The catalogue and wall texts positioned Neel as a radical artist drawn to ‘social justice’. While her oil paintings of transgender people and sex-work activists are still striking, that kind of language is a touch stuffy too. Neel’s famous nudes – of her pre-teen daughter, of a topless, corseted Andy Warhol (his eyes closed as if in prayer), of pregnant women with veiny breasts and swollen calves – don’t deliver homilies or existential lectures. They’re intimate, beady-eyed without being forensic, accepting of the toll just staying alive takes on a body.

Encompassing seven decades of art-making, and giving space for lesser-known periodical work, ‘People Come First’ was capacious but never exhausting. Pieces by Helen Levitt and Jacob Lawrence were brought in to offer intriguing points of connection. Neel’s distance from 20th-century American movements such as Abstract Expressionism or minimalism turns out to have been a strength. She walked her own road. ‘Anarchist humanism’ was how she characterised her vision. It’s tactile and still contemporary, a tireless documentary of resilience and improvisation.

Geoffrey Hendricks and Brian (1978), Alice Neel. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. © The Estate of Alice Neel

Sukhdev Sandhu directs the Colloquium for Unpopular Culture at New York University. His books include Night Haunts (Verso) and London Calling (Harper Collins). He also runs the Text und Töne imprint.

The Winners | Personality of the Year | Artist of the Year | Museum Opening of the Year | Exhibition of the Year | Book of the Year | Digital Innovation of the Year | Acquisition of the Year | View the shortlists