From the May 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

‘Fashioning’ is a useful word for a curator. To be fashioned means to exist in a state of formation. An event or identity takes shape; meaning changes, settles and changes again. For an exhibition as ambitious in scope as ‘Fashioning Masculinities: The Art of Menswear’ at the Victoria and Albert Museum, the word is perhaps a relief. After a raft of blockbuster exhibitions devoted to designers and labels including Alexander McQueen, Balenciaga and Dior, the fashion department has now set its sights on something that is not so much a topic as an open-ended question. Do clothes make the man? And, if they do, how much power do those clothes have to shape our understanding of masculinity?

It is impossible to imagine the V&A putting on an exhibition titled ‘Fashioning Femininities: The Art of Womenswear’. Where on earth would it begin, let alone end? Over the last 300 years or so, ‘fashion’ in the sense of a continually shifting set of trends has been understood as a largely female arena. Women wear fashion. Men wear clothes. Women’s appearances are repeatedly altered by rapid changes in silhouette, hemline and fabric. Men have trousers. ‘Fashioning Masculinities’ is a welcome riposte to such narratives. It makes a compelling argument for menswear being just as flamboyant, vain and varied as womenswear, while also aiming to do away with any kind of entrenched divide between the two.

The exhibition is divided into three sections: ‘Undressed’, ‘Overdressed’, ‘Redressed’. Beginning with the figure of the Greek nude, all rippling muscles and wholly unfunctional drapery, ‘Undressed’ charts a brief history of undergarments and physical ideals. Huge plaster statues of the Farnese Hermes and Apollo Belvedere overlook pale displays of loose muslin shirts, tight Y-fronts, translucent two-pieces and chest binders. Sly shock comes in the form of Vivienne Westwood’s suggestive fig-leaf pants and Jean Paul Gaultier’s trompe l’oeil blazer featuring both pecs and penis. Homoerotic undertones are made explicit in Tom of Finland illustrations and photography by George Platt Lynes and Robert Mapplethorpe.

Conceptions of masculinity are shaped as much by physicality as fabric. Here we see both its embodiment and its subversion, the photos, videos and clothes assembled walking a deliberately wobbly line between straightness and camp. In Work! A Queer History of Modeling (2019), Elspeth H. Brown examines the legacy of the many gay designers, photographers, stylists and art directors who have shaped fashion, describing it as a process of hiding in plain sight: their queer aesthetic ‘laminated’ on to mainstream trends and imagery. A similar process of lamination is revealed here, our understanding of menswear and male beauty having been intimately shaped, in part, by men who desired men.

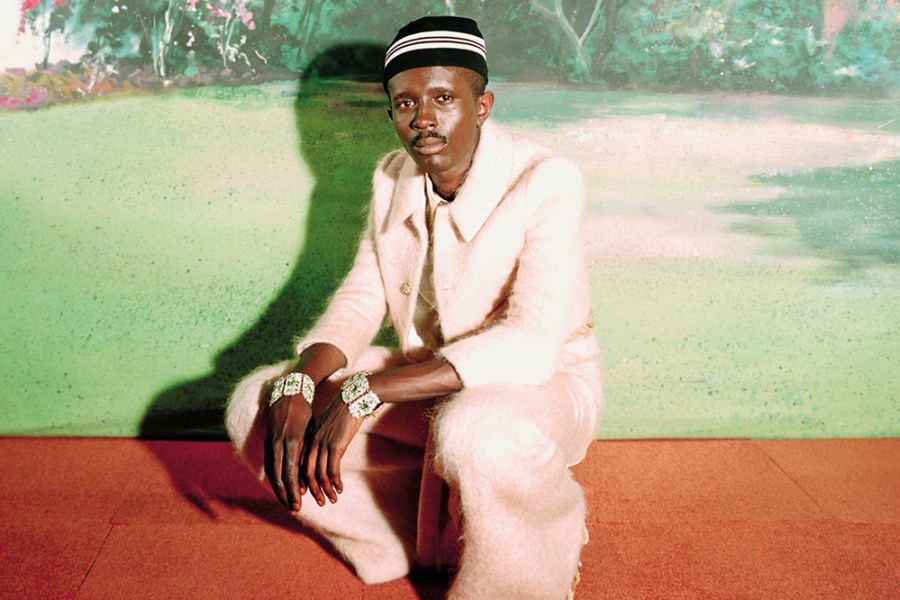

The ‘Overdressed’ section is pure peacockery, with displays of power and wealth, as well as the pleasures of colour and pattern. Clothes rub shoulders with paintings, sculptures and marvellous curios including an intricately carved 18th-century wooden cravat belonging to Gothic novelist and man about town, Horace Walpole. A pleasing line-up of pink garments features too, stretching from Joshua Reynolds’ portrait of the ‘inveterate womaniser’ Charles Coote, 1st Earl of Bellamont, depicted in swathes of blushing satin, to pieces by contemporary designers. Grace Wales Bonner’s fuzzy, quartz-coloured two-piece and Thom Browne’s candy-striped skirt suit with built in codpiece are highlights. Given the exhibition’s largely Western focus, there are also some welcome garments here from designers such as Priya Ahluwalia, who specialises in splicing together more European modes of dress with Indian and Nigerian tailoring and textiles.

Portrait of Charles Coote, 1st Earl of Bellamont (1738-1800), in Robes of the Order of the Bath, (1773–1774), Joshua Reynolds. Photo: © National Gallery of Ireland

‘Redressed’ looks at that most typical of masculine garments: the suit. Usually understood to have started with Regency dandy Beau Brummell, who liked his fabrics neutral and his shoes shone with champagne, this section recreates a timeline that takes us through military uniforms, Hollywood heart-throbs, teddy boys and tuxedo wearers.

At the very beginning of the exhibition, we are greeted by a statement from Gucci creative director Alessandro Michele (Gucci is the exhibition’s main sponsor) about the ‘authoritarian sanctions’ and ‘suffocating stereotypes’ of masculinity. Michele encourages a new understanding of ‘a man who is free to practise self-determination, without social constraints’. Here those pronouncements are brought to life. A procession of black overcoats and suits – reminiscent, I couldn’t help thinking, of the horrifying bankers in Mary Poppins, extolling the virtues of prudent capitalism and colonial plunder – gives way to provocative pieces that impishly mesh the masculine and feminine.

The final room, lined with mirrors to reflect the visitors, focuses on three garments that have gone viral on the Internet and apparently have something to tell us about modern masculinity: the Gucci dress Harry Styles wore on the cover of American Vogue, Billy Porter’s velvet Christian Siriano suit-gown from the Oscars and the white ruffled gown Bimini Bon Boulash wore for the final of Drag Race UK. This trio of outfits provides a crowd-pleasing moment, but reveals the conundrum at the heart of the exhibition: how to reflect on masculinity when categorisations of ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ feel increasingly blurred or even completely out of date? This show’s palpable sense of anxiety is a shame. Menswear is a fascinating topic, in both its traditions and its uproarious subversions. It would have been interesting to learn more about some of those staples of masculinity that have become emblems of both heterosexual virility and camp (denim jeans and leather jackets, for example) and appreciate its liberatory potential as well as its authoritarian constrictions.

Anne Hollander in Sex and Suits (1994) advances the argument that, contrary to popular opinion, womenswear has always been one step behind clothing for men. ‘Gradual “modernisations” of female costumes since 1800 have mainly consisted of trying to approach the male idea more closely,’ she writes, praising menswear for its fluidity and comfort: qualities women have sought for themselves in different epochs in the form of pantaloons, looser silhouettes and designs that have increasingly melded form and function. Ideas like this could have added something spikier to artefacts such as Marlene Dietrich’s suit, displayed on a mannequin leaning back in a louche swagger.

Of course, an exhibition as broad as this is only ever going to provide a glance rather than an in-depth look at the complexities of gender and dress. It is full of thoughtful, unexpected, inclusive and often beautiful displays, but could have taken more risks in what it has fashioned with such rich materials.

‘Fashioning Masculinities’ is at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, until 6 November.

From the May 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?