When a festival of the United Kingdom was announced by Theresa May in 2018 you could almost hear the collective sigh of the nation. It was immediately dubbed ‘the festival of Brexit’ and, after May’s successor as prime minister reiterated his support for the event, that name remained unchallenged, if much mocked. Now that the difficulties that are attending our departure from Europe, let alone those of the past dire year, have combined to such baleful effect, a huzza little more than a year from now with a budget of £120 million must surely strike a flat note. Or can it deliver against the odds?

When the Festival of Britain was announced in 1947, with a launch date of 1951 (to mark the centenary of the Great Exhibition), it had a budget of £414 million (in today’s terms) and was envisaged as an international trade exhibition. But by the time the deputy prime minister Herbert Morrison presented what had become essentially his own scheme to the House of Commons, it had been pruned down to a ‘national display illustrating the British contribution to civilization, past present and future’. Given the austerity of the post-war period, this was quite ambitious enough.

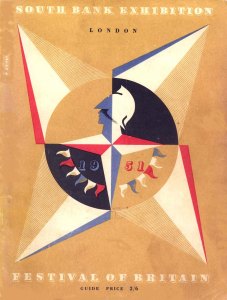

The Festival of Britain emblem, designed by Abram Games

Adrian Forty, in his perceptive essay ‘Festival Politics’, included in A Tonic to the Nation (1976), credits Morrison and his remarkable permanent secretary Max Nicholson with driving the Festival onwards and upwards. Steadfastly non-partisan, it seemed to neatly reflect a nation divided into the camps memorably outlined by the playwright Michael Frayn: Churchillian ‘Carnivores’ versus the designer-led ‘Herbivores’. The right-wingers of the former camp, not to be seen again, as Forty wrote with prescience, ‘until the Common Market debates’, were ranged against Frayn’s ‘radical middle-classes – the do-gooders’. Forty reminds us that the former ‘were silenced by the self-evident popularity’ of the event. Meant as a ‘cheer-up event’, the festival combined the quite serious with the gently encouraging. The soaring Skylon on the South Bank site appeared to some as a ‘a living symbol of rejuvenation’, to others as a gimmick. But like the neighbouring Dome of Discovery these purposeless structures caught the nation’s imagination, far more than well intentioned attempts to roll out the festival around the UK, such as the Land Travelling Exhibition or the festival ship, ‘Campania’. Even if it proved, to borrow Forty’s term, more ‘narcotic’ than ‘tonic’ the event resonated then and still does, 70 years on. Those responsible for Festival 2022 must take comfort from how it (mostly) came right in 1951. They might also recall the chequered story of the Millennium Dome of 2000, another building without a long-term purpose, supervised by Morrison’s grandson, Peter Mandelson.

A view of the South Bank Exhibition from the north bank of the Thames, showing the Skylon and the Dome of Discovery. Photo: Peter Benton/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0)

The key figure in Festival UK* 2022 – the asterisk denoting that a better name is still to be chosen – is its director Martin Green. He may not be a household name but is nonetheless quite ubiquitous; the deus ex machina of the successful ceremonies at the 2012 London Olympics, he also presided over the acclaimed programme for Hull’s year as UK Capital of Culture in 2017. Appointed in January 2020, Green must have had his early plans for Festival UK 2022 blown out of the water by the pandemic, but he has previously demonstrated copper-plated resilience. The ‘cynicism’ (his term) that bedevilled both of those previous ventures gave way to remarkably positive reactions. As he told the Guardian on his appointment, ‘I’ve got form in this’. However, the culture secretary he first discussed plans with, Nicky Morgan, has gone, to be replaced by Oliver Dowden. He or whoever is the minister next year may find it testing to divide their attention between multiple events, ranging across Festival UK 2022, the BBC’s centenary and the Commonwealth Games opening in Birmingham (also Martin Green’s responsibility). Meanwhile, the nation will be marking the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee.

Festival UK 2022 will not be tied to a single site, but involve the public across the four nations. Ten ‘creative teams’ have now been chosen from a longlist of 30 to take their ideas forward, and will be bringing in more freelance contributors to enrich the mix. The blinds are drawn until later this year when proposals will be unveiled. The composition of the teams points to a rich cross-fertilisation between fields – science and technology, music, the visual arts and more. Hints have been dropped about what themes might be covered – so far there’s something on British weather, and on growing your own food.

When Hugh Casson, director of architecture at the South Bank, looked back at the Festival of Britain and the young designers, architects and others who collaborated on his watch, he saw it as a bit like ‘everyone’s pent-up fifth year project’. The playwright Arnold Wesker, who visited the festival in his youth, remembered taking away a kind of diffuse inspiration: a suggestion ‘that one had the spark of something within oneself’. In 2022, it may be a similar sense of vague optimism that will make the difference. In any case, it looks as if the festival will arrive in a bit of a rush, along with its elusive more satisfactory name. Nothing went smoothly in 1951 and the discomfort and, in places, sheer irrelevance of what Brian Aldiss called ‘a memorial to the future’ stayed with many visitors when they looked back on it all. But with a following wind, and the confidence that Martin Green inspires so widely, here’s hoping for the best.

Will the ‘festival of Brexit’ prove a tonic for the nation, after all?

Folk craft: at the Festival of Britain in 1951. Photo: Trinity Mirror/Mirrorpix/Alamy Stock Photo

Share

When a festival of the United Kingdom was announced by Theresa May in 2018 you could almost hear the collective sigh of the nation. It was immediately dubbed ‘the festival of Brexit’ and, after May’s successor as prime minister reiterated his support for the event, that name remained unchallenged, if much mocked. Now that the difficulties that are attending our departure from Europe, let alone those of the past dire year, have combined to such baleful effect, a huzza little more than a year from now with a budget of £120 million must surely strike a flat note. Or can it deliver against the odds?

When the Festival of Britain was announced in 1947, with a launch date of 1951 (to mark the centenary of the Great Exhibition), it had a budget of £414 million (in today’s terms) and was envisaged as an international trade exhibition. But by the time the deputy prime minister Herbert Morrison presented what had become essentially his own scheme to the House of Commons, it had been pruned down to a ‘national display illustrating the British contribution to civilization, past present and future’. Given the austerity of the post-war period, this was quite ambitious enough.

The Festival of Britain emblem, designed by Abram Games

Adrian Forty, in his perceptive essay ‘Festival Politics’, included in A Tonic to the Nation (1976), credits Morrison and his remarkable permanent secretary Max Nicholson with driving the Festival onwards and upwards. Steadfastly non-partisan, it seemed to neatly reflect a nation divided into the camps memorably outlined by the playwright Michael Frayn: Churchillian ‘Carnivores’ versus the designer-led ‘Herbivores’. The right-wingers of the former camp, not to be seen again, as Forty wrote with prescience, ‘until the Common Market debates’, were ranged against Frayn’s ‘radical middle-classes – the do-gooders’. Forty reminds us that the former ‘were silenced by the self-evident popularity’ of the event. Meant as a ‘cheer-up event’, the festival combined the quite serious with the gently encouraging. The soaring Skylon on the South Bank site appeared to some as a ‘a living symbol of rejuvenation’, to others as a gimmick. But like the neighbouring Dome of Discovery these purposeless structures caught the nation’s imagination, far more than well intentioned attempts to roll out the festival around the UK, such as the Land Travelling Exhibition or the festival ship, ‘Campania’. Even if it proved, to borrow Forty’s term, more ‘narcotic’ than ‘tonic’ the event resonated then and still does, 70 years on. Those responsible for Festival 2022 must take comfort from how it (mostly) came right in 1951. They might also recall the chequered story of the Millennium Dome of 2000, another building without a long-term purpose, supervised by Morrison’s grandson, Peter Mandelson.

A view of the South Bank Exhibition from the north bank of the Thames, showing the Skylon and the Dome of Discovery. Photo: Peter Benton/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0)

The key figure in Festival UK* 2022 – the asterisk denoting that a better name is still to be chosen – is its director Martin Green. He may not be a household name but is nonetheless quite ubiquitous; the deus ex machina of the successful ceremonies at the 2012 London Olympics, he also presided over the acclaimed programme for Hull’s year as UK Capital of Culture in 2017. Appointed in January 2020, Green must have had his early plans for Festival UK 2022 blown out of the water by the pandemic, but he has previously demonstrated copper-plated resilience. The ‘cynicism’ (his term) that bedevilled both of those previous ventures gave way to remarkably positive reactions. As he told the Guardian on his appointment, ‘I’ve got form in this’. However, the culture secretary he first discussed plans with, Nicky Morgan, has gone, to be replaced by Oliver Dowden. He or whoever is the minister next year may find it testing to divide their attention between multiple events, ranging across Festival UK 2022, the BBC’s centenary and the Commonwealth Games opening in Birmingham (also Martin Green’s responsibility). Meanwhile, the nation will be marking the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee.

Festival UK 2022 will not be tied to a single site, but involve the public across the four nations. Ten ‘creative teams’ have now been chosen from a longlist of 30 to take their ideas forward, and will be bringing in more freelance contributors to enrich the mix. The blinds are drawn until later this year when proposals will be unveiled. The composition of the teams points to a rich cross-fertilisation between fields – science and technology, music, the visual arts and more. Hints have been dropped about what themes might be covered – so far there’s something on British weather, and on growing your own food.

When Hugh Casson, director of architecture at the South Bank, looked back at the Festival of Britain and the young designers, architects and others who collaborated on his watch, he saw it as a bit like ‘everyone’s pent-up fifth year project’. The playwright Arnold Wesker, who visited the festival in his youth, remembered taking away a kind of diffuse inspiration: a suggestion ‘that one had the spark of something within oneself’. In 2022, it may be a similar sense of vague optimism that will make the difference. In any case, it looks as if the festival will arrive in a bit of a rush, along with its elusive more satisfactory name. Nothing went smoothly in 1951 and the discomfort and, in places, sheer irrelevance of what Brian Aldiss called ‘a memorial to the future’ stayed with many visitors when they looked back on it all. But with a following wind, and the confidence that Martin Green inspires so widely, here’s hoping for the best.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

Share

Recommended for you

‘The Southbank Centre suffers from architectural self-loathing’

Plans for a rooftop bar at the Royal Festival Hall have thankfully been scrapped, but questions remain over the stewardship of the Southbank centre

The culture minister should take an interest in museums – but he can’t tell them how to interpret the past

It’s no bad thing for the government to sit down with museum directors, says Charles Saumarez Smith, but imposing its own version of history is another matter

Has the UK government abandoned the arts?

Former arts minister Ed Vaizey and leading culture writer Charlotte Higgins on whether the government should be doing more for the hard-hit arts sector