From the April 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

When Florine Stettheimer arrived in Manhattan in 1914, she found the city undergoing a triumphant expansion – skyscrapers shooting heavenwards, Wall Street booming, theatres and department stores filled with elegant socialites eager to be seen, new forms of art being forged and debated in galleries, salons and jazz bars. Stettheimer, an artist in her forties who had never shown her work in public, was convinced that in the noise and bustle of the city she had found her subject. In a notebook, she expressed her excitement in verse, remarking on an ‘amusing thing / Which I think is America having its fling / And what I should like is to paint this thing’. The work she produced in response to urban modernity, Barbara Bloemink argues in this rich new biography, makes Stettheimer ‘one of the most innovative and significant artists of the twentieth century’.

Florine Stettheimer photographed in c. 1917–20 by Peter A. Juley Sons.

In her lifetime, Stettheimer was well-known in the New York art scene: she and Georgia O’Keeffe were often the only women featured in major group shows; shortly after her death in 1944, she became the first woman to receive a full retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, curated by her close friend Marcel Duchamp. Thereafter, her reputation ebbed. Most of her furniture and theatrical designs were destroyed, her paintings largely consigned to museum basements and storage units. The author of a biography published in 1963, which painted Stettheimer as an eccentric recluse, hypersensitive to criticism, admitted that he had invented and exaggerated much of her life story; nonetheless, the image stuck of Stettheimer as an outsider artist, undercutting her formal training and professional commitment. Bloemink, who has spent decades researching Stettheimer (and co-curated a retrospective at the Whitney in 1995), sets out to debunk these myths. She positions Stettheimer as a pioneer of multi-disciplinary practice, a central figure in the 20th-century avant-garde, and a feminist determined to challenge anti-Semitism and racism, as well as gender stereotypes, through her exuberant, intensely personal work.

Stettheimer was born in 1871 into a wealthy New York Jewish family. When she was seven, her father vanished, apparently to Australia; her mother, Rosetta, took her five children to Europe, where Florine spent most of her first 40 years, revelling in the lively clash of old and new that she witnessed in galleries and studios across Italy, France, Spain and Germany. She admired the flamboyant curves of rococo decoration and the forms and figures of Botticelli and other Old Masters; from Giotto she learned how a complex, chaotic scene might be structured. But her most transformative experience was in Paris, where Cubism was taking off and Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes were in town. Stettheimer returned again and again to the ballet: in its synthesis of forms, its modern energy, its stylised sets and vibrant colour she found a visual vocabulary that would inform her own style.

Cathedrals of Art (1942–44), Florine Stettheimer. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

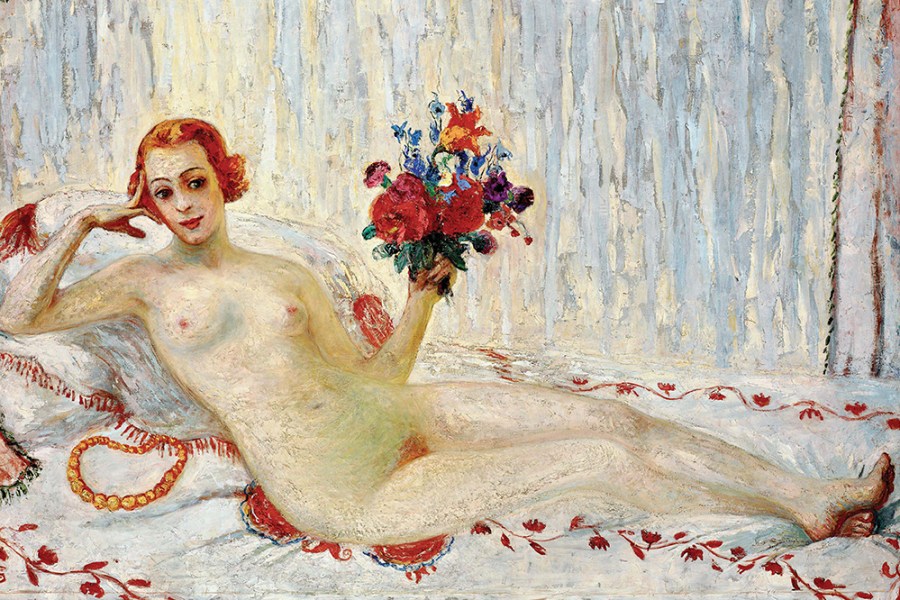

As if declaring her intent to command space and attention, on her return to New York Stettheimer scandalised friends with A Model (Nude Self-Portrait) of 1915, one of the first instances in Western art history of a female artist painting herself naked. Until this point, Stettheimer had mostly created floral still lifes, which featured in her debut solo exhibition in October 1916 at Knoedler & Company, for which she decorated the gallery with furnishings and draperies to resemble her own bedroom. After 1916, her work began to focus on narrative set-pieces – lake picnics, cocktail parties – populated by the literary and artistic celebrities who crowded to the salons she and her sisters Carrie and Ettie held in the ornate mansion-apartment they shared with their mother on the Upper West Side. She appears in a striking number of her own paintings, often standing at an easel in painting smock, surrounded by activity. La Fete a Duchamp (1917) compresses the narrative of an evening into one canvas: Duchamp arrives in a sports car in one corner, pops up again in the centre to be greeted by Florine, then is toasted by Ettie on the right-hand side while other guests mingle, drink and fall asleep. Her Cathedral series is a riot of colour and activity: Spring Sale at Bendel’s shows brawling shoppers contorting like acrobats over luxury goods, while The Cathedrals of Art (1942) distils an ongoing rivalry between the benefactors of the Whitney, the Met and MoMA into a tussle over a cherubic baby.

Stettheimer’s belated break came in 1934, when she was asked to design the set for Gertrude Stein and Virgil Thomson’s opera Four Saints in Three Acts, finally achieving her ambition to work for the theatre. The stage erupted in a cloud of lace and cellophane, lit by white lightbulbs, which one critic called ‘a child’s dream of rock candy’. The opera was a resounding success, praised for the unconventionality of music and libretto and the skill of its all-Black cast. Stettheimer’s designs were adapted for department-store windows, while galleries sought her out – without success, for Stettheimer refused to sell her work, preferring it to be seen in the cocoon of her home, whose furnishings, inhabitants and atmosphere formed an inextricable part of her art. Whether from discretion or lack of evidence, Bloemink doesn’t speculate too far on the psychological aspects of the private world Stettheimer and her sisters inhabited. I’m intrigued to know more about Ettie, who wrote two autobiographical novels, and Carrie, who spent nearly two decades creating a doll’s house featuring a miniature art museum (on show at the Museum of the City of New York).

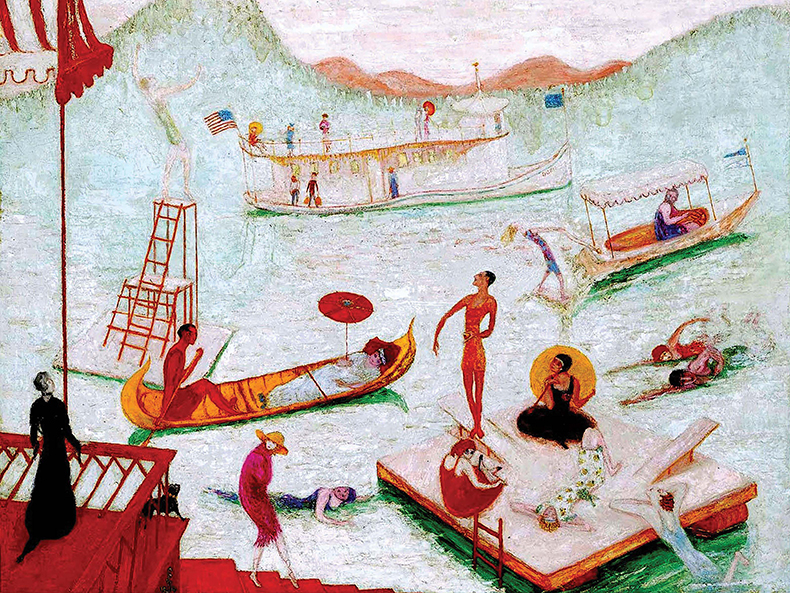

Lake Placid (1919), Florine Stettheimer. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Bloemink is especially good on the granular detail of Stettheimer’s process – her mixing of colour and applied paint, the heavy use of white pigment that gives her work a luminescent quality – and on close readings of individual works, particularly when parsing the intricate symbolism of places (Black beach-goers on the segregated shores of Asbury Park, or at Lake Placid, a focus of protests against anti-Semitism). The book is marred by typographical errors – misspelled names, missing words, back-to-front quotation marks – but that’s almost made up for by more than 100 full-colour illustrations, which entreat readers to lose themselves in Stettheimer’s work: festive, celebratory, radical, modern.

Bloemink is especially good on the granular detail of Stettheimer’s process – her mixing of colour and applied paint, the heavy use of white pigment that gives her work a luminescent quality – and on close readings of individual works, particularly when parsing the intricate symbolism of places (Black beach-goers on the segregated shores of Asbury Park, or at Lake Placid, a focus of protests against anti-Semitism). The book is marred by typographical errors – misspelled names, missing words, back-to-front quotation marks – but that’s almost made up for by more than 100 full-colour illustrations, which entreat readers to lose themselves in Stettheimer’s work: festive, celebratory, radical, modern.

Florine Stettheimer: A Biography by Barbara Bloemink is published by Hirmer.

From the April 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?