The exhibition design of ‘La Forêt Magique’ at the Palais des Beaux-Arts invokes more than the visual aspects of a forest. Darkened walls and softly carpeted floors are animated by chirping crickets and bird songs, the ambient effects replicating to some degree the sensory disorientation we experience in the woods. Part of Lille 3000, a citywide arts festival, the exhibition opens with the words of botanist and forest advocate Francis Hallé. Hallé is dedicated to reviving primary forests in Europe, which were largely lost with the rise of industrial forestry in the 19th century. Excerpts from his manifesto, calling for an area of forested land entirely free from human intervention, wrap the exhibition’s entrance, putting politics on the surface. Inside, four thematic areas, from a section on trees to views of sacred, haunted, and finally enchanted woods, track a long history of human involvement with forests even as the show proposes that we should ultimately leave them alone.

The oldest object in the show is a terra cotta neo-Assyrian column modelled after a date palm trunk (911–604 BC); the most recent is an immersive video installation from 2020 by Jakob Kudsk Steensen, which plunges us into a computer-generated ‘virtual ecosystem’. The sweeping perspective suggests that humans have an innate fascination with forests, which have become metonyms for nature writ large. This is underscored by the inclusion, throughout the exhibition, of perspectives from ecologists; one wall text notes, ‘Marvelling at the spectacle of nature is the surest way to truly look at trees as living, non-human members of our family who deserve our attention.’ Yet if marvelling is all that is required, surely we would do well to visit actual forests rather than an exhibition dedicated to them.

Study of the Trunk of an Elm Tree (c. 1821), John Constable. Victoria and Albert Museum, London

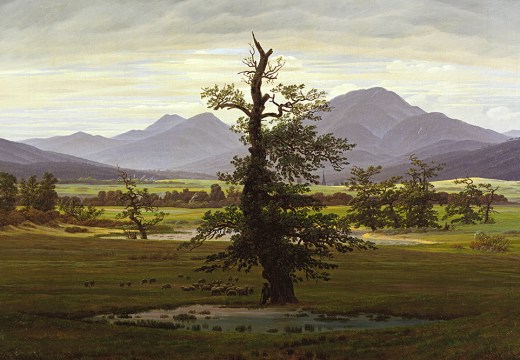

An unstated irony of the exhibition is that in the same moment that vast areas of European woodlands were being subjected to scientific sylviculture, forests became celebrated emblems of ‘nature’ through paintings such as John Constable’s Study of an Elm Trunk (1821) and Théodore Rousseau’s view of old oaks in Fontainebleau (1836), both included in the show.

Representing forests as ideal, untouched nature occludes a history of human forest management that dates to the Neolithic period and reached an industrial scale in the 19th century. Forests are a technology as much as environment. This hybrid aspect appears in Mat Collishaw’s Albion (2017). The ghostly apparition of one of England’s oldest trees, an oak in Sherwood forest, is projected by means of a 19th-century technique known as ‘Pepper’s Ghost’. A haunting, floating hologram, the installation makes no pretence to the natural. The tree itself, more than one thousand years old, is supported via struts and chains, without which it would have long ago collapsed. The technical apparatuses that both prop up the tree and make its appearance within the exhibition possible underscore a complex intertwining of human and environment that tell a fuller story than one of straightforward wonder.

Albion (2017), Mat Collishaw. Courtesy Mat Collishaw; © ADAGP Paris 2022; the artist

Refreshing, then, to find conceptions of forests as cultural entities in the cultures of Indigenous Amazonians in a nearby exhibition at Tripostal. Organised by the Fondation Cartier, ‘Les Vivants’ draws heavily on the foundation’s collections of Amerindian drawings, filling the expansive second floor of the former sorting-office facility with the work of Jaider Esbell (Makuxi), Ehuana Yaira and Joseca (Yanomami), Bane, Isaka and Mana (Huni Kuin), and Sheroanawe Hakihiiwe (Yanomami). Many of the communities the artists come from practice slash-and-burn agriculture, cultivating an active and dynamic relationship with woodlands rather than an artificially enforced separation. Myths, traditions, and beliefs are chronicled in drawings that range from simple pen outlines to intricately patterned evocations of dense vegetation. This is not, however, an example of a world apart: these drawings engage equally with the realities of our present moment. The threat of destruction looms in images that feature the heavy machinery of unchecked forest clearance.

The overall theme of Lille 3000 is ‘Utopia’, a form of wishful imagining at a time when so much feels dystopic. Utopias are ultimately nowhere. But our forests are here, now, and as thousands of acres burn across southern France this summer it will take more than magic to save them.

‘La Fôret Magique’ is at the Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille, until 19 September as part of the ‘Lille 3000: Utopia’ season.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?