As surprising as it may seem today, when Frank O’Hara died in the summer of 1966 in an accident on Fire Island he was better known as a curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York than as a poet. The headline of his New York Times obituary read ‘Frank O’Hara, 40, Museum Curator’, followed by a subheading that treated his poetry as an afterthought: ‘Exhibitions Aide at Modern Art Dies – Also a Poet.’ Today he is generally regarded as one of the most important and influential figures in the history of 20th-century poetry.

Just after moving to New York in 1951, O’Hara scored a position selling postcards at the front desk of MoMA, primarily because he wanted free access to the Matisse exhibition then showing. He quickly immersed himself in the art world, drinking and talking the night away with Abstract Expressionist painters and young poets at the Cedar Tavern and the Club, both legendary artists’ hangouts. After a two-year stint working at the front desk, O’Hara left the museum, only to return in 1955 as an assistant to Porter McCray, director of the International Program. Rather miraculously, given his lowly start, he worked his way up through the ranks. At the time of his death, he had been named an associate curator and had begun organising exhibitions himself, including major retrospectives of Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, and David Smith. The poet John Ashbery wrote in his introduction to his close friend’s Collected Poems that American painting – and Abstract Expressionism in particular – ‘absorbed Frank to such a degree, both as a critic for Art News and a curator at the Museum of Modern Art, and as a friend to the protagonists, that it could be said to have taken over his life’.

Although O’Hara’s association with MoMA has never been a secret, the museum has rarely highlighted it – until now. The newly renovated museum, which opened to the public on 21 October, has decided to devote an entire room to its most famous curator, as part of its mission to ‘rethink’ the story it tells about the evolution of modern art. Thoughtfully curated and designed, ‘Frank O’Hara, Lunchtime Poet’ in the 1940s–1970s section of the collection galleries will appeal both to O’Hara aficionados and newcomers alike, who will come away with a good sense of O’Hara’s exuberant contributions as poet, curator, and collaborator with artists.

Double Portrait of Frank O’Hara (1955), Larry Rivers. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: © Estate of Larry Rivers/VAGA at ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Upon entering the room, one is greeted by a well-known passage from O’Hara’s poem ‘Steps’, stencilled in black on one wall: ‘oh god it’s wonderful / to get out of bed / and drink too much coffee / and smoke too many cigarettes / and love you so much.’ Nearby, two versions of the young O’Hara’s face, at slightly different angles, stare intently at passersby. This double portrait by Larry Rivers provides a glimpse of how important O’Hara was as a recurring subject for art – indeed, his many artist friends, from Alice Neel to Elaine de Kooning to Alex Katz, loved the challenge of trying to capture him in paint. As Rivers once said of his many renderings of O’Hara, ‘I always felt I was close to getting him but I never did, so I kept on trying’ – which may explain the impulse behind the double portrayal on display.

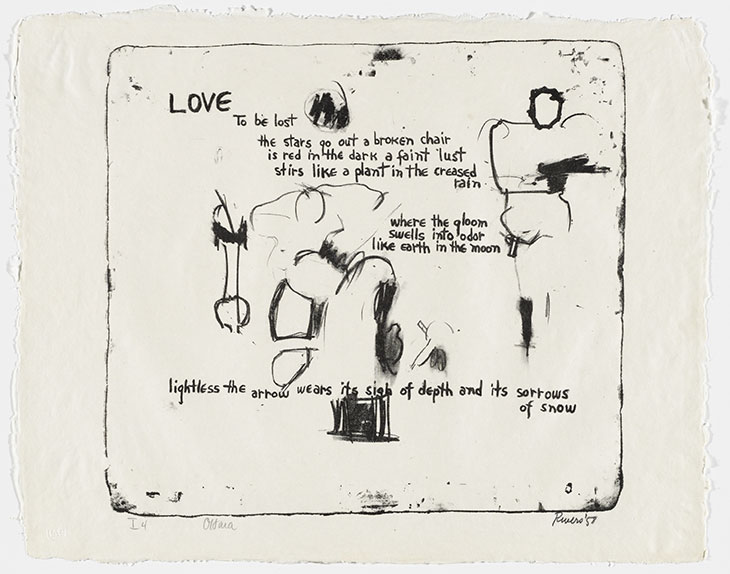

At the centre of the room there are a couple of armchairs and a coffee table with a copy of O’Hara’s Lunch Poems waiting to be picked up and read. There’s also a healthy dose of O’Hara memorabilia, including some photographs of him in his office at the museum or in black tie at exhibition openings, along with a shelf of rare first editions of the handful of books he published during his lifetime. His many collaborations are represented by two examples from Stones, the series that he and Rivers completed in 1959. To create these playful, funny lithographs, the poet and painter worked side by side, passing the lithography crayon back and forth, O’Hara responding to Rivers’s drawings with words and vice versa.

Love from Stones (1957; published by Universal Limited Art Editions in 1960), Larry Rivers. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: © Estate of Larry Rivers/VAGA at ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

One wall has a large video monitor playing some of the only extant footage of O’Hara, filmed for public television in 1966 a couple of months before his sudden death. The clip is quintessential O’Hara, the poet as a blur of motion and creative activity, typing up lines for an experimental movie he is making with the artist Alfred Leslie, talking on the phone with a friend, chain-smoking, and patting a cat who has jumped up on his lap, before reading some of his best-known poems while sitting at his desk, including ‘The Day Lady Died’ and ‘Having a Coke with You’, in which he compares his lover’s beauty to some of his favorite works of art: ‘I look / at you and I would rather look at you than all the portraits in the world / except possibly for the Polish Rider occasionally and anyway it’s in the Frick / which thank heavens you haven’t gone to yet so we can go together for the first time.’

The display also provides a glimpse into O’Hara’s museum work, thanks to some materials gathered from MoMA’s archives – like the yellowed pages on which he jotted down titles of paintings to be included in an upcoming exhibition in Brazil, and a spiral-bound notebook he used while accompanying a travelling exhibition to Spain, opened to one of its back pages. Here we see, in O’Hara’s sloping hand in blue ink, an early draft of ‘Now That I Am in Madrid and Can Think’, one of his tender love poems (with an earlier, slightly different title: ‘Now That Iberia Has Landed Me Here in Madrid and I Can Think’). The presence of this first draft in one of O’Hara’s work notebooks gives us a tangible sense of how closely intertwined his museum life and poems always were.

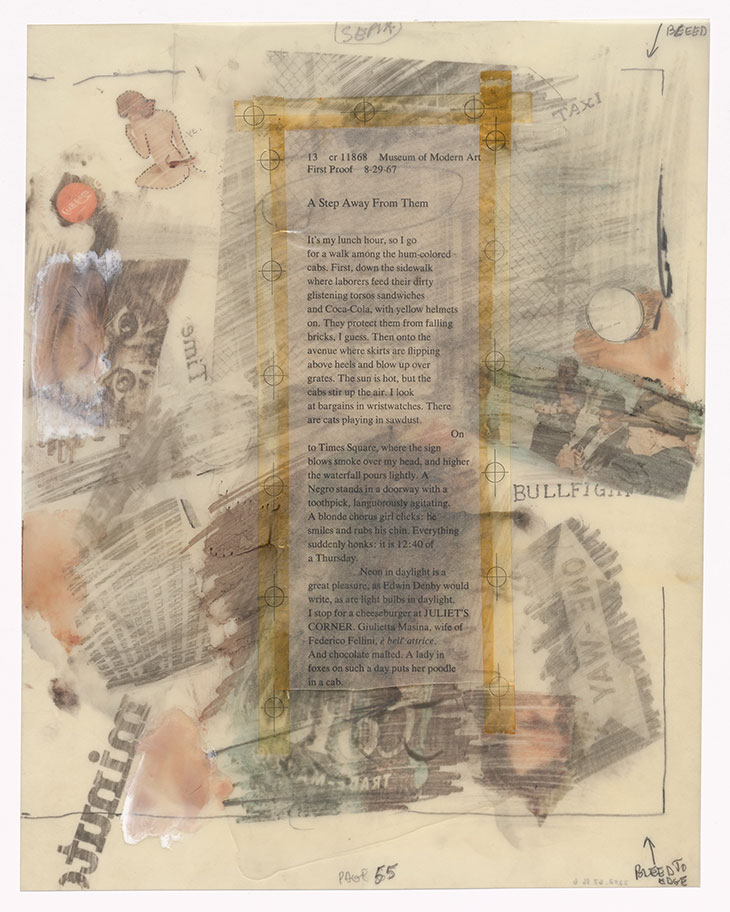

Preparatory drawing for In Memory of My Feelings (1967), Robert Rauschenberg. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation/VAGA at ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Soon after O’Hara’s death, MoMA published In Memory of My Feelings, a selection of his poetry accompanied by commissioned drawings by many of the artists who were close to him. It is interesting to see the 21 preparatory drawings the artists did for the 1967 volume, which testify to the remarkable range of visual artists – from a variety of traditions and schools – who felt a connection to O’Hara, including Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, Philip Guston, Claes Oldenburg, Roy Lichtenstein, Joan Mitchell, Nell Blaine, Jasper Johns, Joe Brainard, and Jane Freilicher. Some of these are quite different from the final versions that appear in the collection. In particular, Rauschenberg’s preparatory drawing for O’Hara’s poem ‘A Step Away from Them’ is a revelation: more colourful and dynamic, and more quintessentially Rauschenberg, than the monochromatic, sepia-toned version in the book itself. Collaged images – of a cat’s face, a woman’s body, words in different sizes and typefaces, a ‘One Way’ street sign, charcoal smears and smudges – all float around and over the text of the poem in different shades and colours. The work points to the fact that O’Hara and Rauschenberg share a deeper affinity than has often been noted – in their fascination with cast-off, found materials, and their love for the city and its electric energy.

The story of Frank O’Hara and modern art – or even just O’Hara and MoMA – is perhaps too rich to contain in a single albeit tightly packed room. But I couldn’t help daydreaming about other works and pairings that could have been included: what if MoMA had mounted its Larry Rivers canvas Washington Crossing the Delaware (1953) next to O’Hara’s poem ‘On Seeing Larry Rivers’ Washington Crossing the Delaware at the Museum of Modern Art’? Or had hung Pollock’s monumental painting next to O’Hara’s ‘Digression on Number 1, 1948’? It would have been welcome, too, to have received a fuller sense of O’Hara’s complex, sometimes controversial, role as curator, art critic, and friend to the artists whose work he helped enshrine in the museum. (Waldo Rasmussen, his friend and fellow MoMA curator, once noted that O’Hara’s lack of professional credentials in art history or museum work put him ‘under suspicion as a gifted amateur’, and also acknowledged that O’Hara’s ‘very closeness to the artists was questioned as a danger to critical objectivity’.) What if the museum had explored his role as a crucial bridge between the Abstract Expressionist titans he so revered and Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Alex Katz, and the other Neo-Dada and Pop art ironists of the later 1950s and ’60s, whose work he also championed? Hopefully, one day the museum will make use of its holdings and archives to put together an even fuller exhibition on O’Hara, expanding on the excellent show curated by Russell Ferguson at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles in 1999, which featured an array of O’Hara’s collaborations, works inspired by his poems, and portraits of the poet himself.

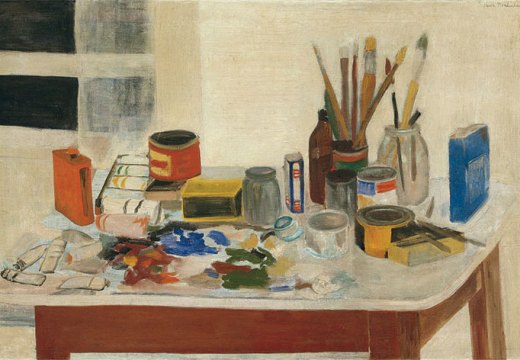

Preparatory drawing for In Memory of My Feelings (1967), Jane Freilicher. The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Still, this display stands as an important chapter in the story of O’Hara’s reception and legacy. It is also an example of MoMA’s effort, in its new incarnation, to tell a more complicated story of modern art, in which works from a variety of media, including film, music, dance, and literature, co-exist and cross-pollinate. By paying tribute to O’Hara, the museum acknowledges the intense dialogue between painting and poetry in the 20th century – also represented in an earlier collection gallery with the inclusion of La Prose du Transsibérien et de la Petite Jehanne de France (1913), the wonderful collaborative artists’ book by the poet Blaise Cendrars and painter Sonia Delaunay. The idea that a top curator at a major museum could also be a prolific, prominent avant-garde poet, with no formal training in art history or museum studies, is rather unimaginable today. As Peter Schjeldahl recently noted, O’Hara’s death in 1966 ‘ripped the heart out of an overlap of artistic and literary communities in New York. He couldn’t be replaced.’ Moving through the rest of the permanent collection after encountering the O’Hara room, one can’t help but feel a twinge of nostalgia, a loss of possibility.

It seems wise that the museum has finally decided to give Frank O’Hara this somewhat belated recognition within its hallowed halls – he is certainly one of the best and most charming ambassadors MoMA has ever had. As he writes in ‘Digression on Number 1, 1948’, one of his many poems about the joys of working among the riches of the Museum of Modern Art:

A fine day for seeing. I see

ceramics, during lunch hour, by

Miró, and I see the sea by Léger;

light, complicated Metzingers

and a rude awakening by Brauner,

a little table by Picasso, pink.

I am tired today but I am not

too tired. I am not tired at all.

There is the Pollock, white, harm

will not fall, his perfect hand

and the many short voyages. They’ll

never fence the silver range.

‘Frank O’Hara, Lunchtime Poet’ is at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?