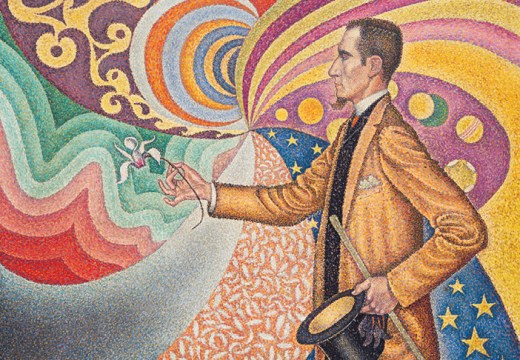

In 2002 the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles paid a reported $3m–$5m for a sculpture believed to be by Gauguin. Now the museum has reattributed Head with Horns to an unknown artist, as reported by the art historian and Van Gogh expert Martin Bailey in the latest issue of the Art Newspaper. In November 2009, Bailey wrote an in-depth article on the sculpture for Apollo that explored the question of its attribution. The article is republished in full below.

One of Gauguin’s most important (and expensive) sculptures may not be quite what it seems. Head with Horns, which was acquired by the Getty Museum in 2002, is a mysterious work, which reappeared after it had been missing for a century. However, a photograph from the French colonial archives reveals that this wooden sculpture was once regarded as having been made by a Polynesian craftsman.

Head with Horns was first exhibited in 1997, when it was unveiled at the Fondation Maeght in Saint-Paul, on loan from a private collection. The sculpture had long been known about, since two photographs of it were glued into the illustrated version of Gauguin’s Tahitian album Noa Noa, which was completed in the late 1890s. However, until its recent re-emergence the actual sculpture had never been seen, and was assumed to have been lost during Gauguin’s lifetime.

In 1998 Head with Horns was lent to the Gauguin exhibition at the Fondation Pierre Gianadda in Martigny. Its third presentation was at the Metropolitan Museum, in a show of Gauguin works from New York collections that opened on 18 June 2002. Just nine days later it was formally announced that the Getty Museum had privately purchased Head with Horns. Although the price was not disclosed, it was reported to have been over $3m, a record for a Gauguin sculpture. The Getty has not named the previous owner, but we understand that it was Wildenstein, the gallery whose family foundation publishes the catalogue raisonné of Gauguin’s paintings . Wildenstein is believed to have acquired the sculpture in Switzerland after World War II. [The museum’s catalogue now states that Wildenstein acquired the work from a private collection in Switzerland in ‘about 1993’.]

The Getty [at the time of writing in 2009] dates Head with Horns to 1895-97, during the early years of Gauguin’s second stay in Polynesia. In announcing the acquisition, the museum suggested that that it ‘may be a symbolic self-portrait, as the sculpture suggests Gauguin’s own features, possibly mixed with the attributes of Tahitian natives.’

The attribution of Head with Horns has not been seriously discussed in print, but since its rediscovery two illustrations have emerged that raise questions. The first, dating from 1899, is in a booklet by Jules Agostini, L’Océanie française: Les Iles sous le Vent. On the last page, there is an engraving of Head with Horns, with the caption ‘Idole des Iles sous le Vent’ (Les Iles sous le Vent, or Leeward Islands, comprise the part of French Polynesia lying to the west of Tahiti). The engraving is clearly based on the left-hand photograph in Noa Noa, which depicts the sculpture straight on.

Gauguin first stayed in Tahiti from 1891 to 1893, before returning to France for two years. He arrived back in Tahiti’s capital, Papeete, on 9 September 1895, and met Agostini, who was head of public works, very shortly afterwards. They both sailed on L’Aube on 26 September, for a voyage to Huahine, Bora Bora and Raiatea-Tahaa (Iles sous le Vent), on a French government mission to reestablish colonial control. Gauguin was invited and presumably curious to see the outlying islands. The voyage took only a few days and L’Aube returned to Papeete in early October.

Gauguin and Agostini remained friends. In November 1895 Gauguin moved to the village of Punaauia, eight miles south of Papeete. Agostini later took a photograph of the exterior of Gauguin’s wooden house, built in June 1897. Agostini finally left Tahiti in January 1898.

It is difficult to see how Agostini could have miscaptioned the image of Head with Horns in his 1899 booklet. He was a friend of Gauguin, and would presumably have known whether the sculpture had been made by him or a Polynesian. Agostini, who was well-informed about anthropology, was methodical in the recording of his photographs. It is possible that the image was miscaptioned by the publisher, but this seems unlikely since nearly all the images in the booklet are engravings based on photographs by Agostini, who was then back in France, and would have been closely involved in the publication. Had a mistake been made, it is perhaps surprising that there is no record of any complaint from Gauguin, since the modestly-priced (15 centimes) booklet presumably circulated among the French community in Polynesia.

We have also discovered that a photograph of Head with Horns (straight-on version) was published in 1931, under the caption ‘Iles Marquises: Idole’, with a credit to ‘Office colonial’. This appeared in Emile Bayard’s book les styles coloniaux de la France and appears to have been unknown to Gauguin scholars, who have understandably concentrated on the literature of Oceania. The Marquesas Islands lie to the north of Tahiti, and it is surprising that the ‘idole’ is said to come from there, rather than Les Iles sous le Vent, but it is possible that Bayard linked the photograph with Noa Noa (Gauguin later moved to the Marquesas) or with the traditional horn-like hairstyle of young men from the Marquesas Islands. The original photograph remains untraced.

The fact that Head with Horns was published as a Polynesian sculpture in 1899 and again in 1931 raises questions about the attribution. Its provenance also remains a mystery. Gauguin probably no longer had the sculpture by the late 1890s, since although he reproduced it in three graphic works, these all appear to have been drawn from the two photographs in Noa Noa. The Woodcut with a Horned Head and the drawing Polynesian Beauty and Evil Spirit (together with a monotype print on the verso) show the three-quarters view, with the images of the horned head in reverse in both prints. The monotype Tahitian Woman and Devil depicts the straight-on view. All three date from around 1898–1900, about the time that Noa Noa was completed.

The sculpture is unsigned, and Gauguin tended to sign (or monogram PGO) his major works, particularly those he gave away to friends or sold. Head with Horns is not referred to in his surviving correspondence. Nor is it among items recorded in Gauguin’s possession at his death. There is no trace of it being acquired by one of the collectors or dealers who came to Tahiti in the early 20th century in search of his works. Although Gauguin collected photographs of artworks by others, only a single image survives of one of his own pieces photographed in Polynesia during his lifetime.

Head with Horns (before 1894), artist unknown. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Turning to its physical condition, the narrow, circular base of the sculpture (between the head and the darker plinth) is the same wood as the head, but appears to have been turned on a lathe. No other examples are known of Gauguin sculptures which have been worked in this way. Head with Horns had developed unsightly cracks by the mid 1890s, particularly its left horn and the side of its right eye. Although usual in an ethnographic piece of some age this would be surprising in a finely finished modern European sculpture. What is particularly unusual, is the plinth – probably a ‘found object’. No one has suggested that this was made by Gauguin, although he may have added it. No other Gauguin sculptures are known with an original plinth of any substantial size.

An examination of the wood does not help the question of authenticity. The head is of sandalwood, which is hard and slow to work. It was common in Polynesia in the early 19th century, but had become comparatively rare by Gauguin’s time (and expensive for a piece of this size). The plinth is lacewood, which is not found in Polynesia, although it grows in Australia and elsewhere in the Pacific.

It is particularly difficult to reach a judgement on whether the sculpture is by Gauguin because it is unclear what the head actually represents. The face shares the characteristics of both a European (the thin lips) and a Polynesian (the flat nose). As the Getty points out, it could either be a self-portrait of Gauguin or a Marquesan man with two bunches of hair (worn as an expression of power). Arguably, this very ambiguity is evidence that it is indeed a Gauguin. In terms of technique, it is more ‘polished’ than Gauguin’s more expressionist carvings, although he did also work in this style. Gauguin’s sculptures, whether wood or clay, are very diverse and imaginative, which again makes attribution difficult.

But if Head with Horns is not by Gauguin, who made it? The 1899 Agostini woodcut and the photograph in the 1931 Bayard book suggest that it could be an authentic Polynesian work. However, there was no great tradition of wood sculpture there, and relatively few pieces survive from before European settlement in the early 19th century. There are certainly no known examples of sculptures similar to Head with Horns by indigenous craftsmen. Another suggestion is that it was made by a European in Polynesia, but not Gauguin. It could possibly have been a sailor who had incorporated elements of what he perceived to be traditional Polynesian art (sailors often had time on long sea voyages and would carve wood or bone).

The sculpture could also have been made by a Polynesian craftsman for sale to a visiting European. If so, Gauguin and Agostini might have believed it to be a surviving example of traditional art, since there were so few authentic examples that they could have seen. This would explain why Agostini published it as an ‘idole’ and why Gauguin included it in his graphic work. A final suggestion is that Head with Horns could possibly have been an unusual collaboration between Gauguin and a Polynesian craftsman.

Interestingly, while most American scholars accept Head with Horns as by Gauguin, some leading French scholars remain doubtful about the attribution, although they have been discreet about expressing it. The sculpture was not requested for the major 2003–04 exhibition ‘Gauguin Tahiti: The Studio of the South Seas’ at the Grand Palais in Paris and Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. There is a revealing difference between the two exhibition catalogues for ‘Gauguin Tahiti’. In the French edition, the page of Noa Noa with the Head with Horns images is reproduced, with the caption: ‘Bought by Gauguin at Raietea [the island in the Les Iles sous le Vent visited by him in 1895]’. However, the slightly later English-language edition reads: ‘Two photographs of Gauguin’s sculpture of a Polynesian niho (head of a horned god)’.

Head with Horns may well be an authentic Gauguin, and the Getty certainly takes this view. David Bomford, its Associate Director for Collections, stresses that the museum has from the start been aware of the arguments surrounding the piece and knew about the Agostini booklet when it acquired the sculpture. He believes that Agostini used Gauguin’s sculpture in his 1899 publication as a final image ‘to conjure up the general idea of an Oceanic myth’.

Even if Head with Horns is not by Gauguin, it certainly deserves to be in a major museum. It was a very important and valued object for the artist, as shown by his insertion of the photographs in Noa Noa and use of the image in three works. It is fortunate that this rediscovered sculpture has ended up at the Getty, an institution highly committed to research.

This article was published in the November 2009 issue of Apollo, accompanied by further images and footnotes which have here been omitted. Click here to download a PDF of the article as it originally appeared.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam got its rehang right?