The exhibition ‘Baselitz – Academy’ at the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice gathers work that goes right back to the beginning of Georg Baselitz’s career, when he was still a student in West Berlin in the years around 1960, but is hardly a retrospective. There are long gaps (barely anything from the ’80s or ’90s, for example), and the focus is on lesser-known paintings, particularly works that show the artist’s connection to Italy.

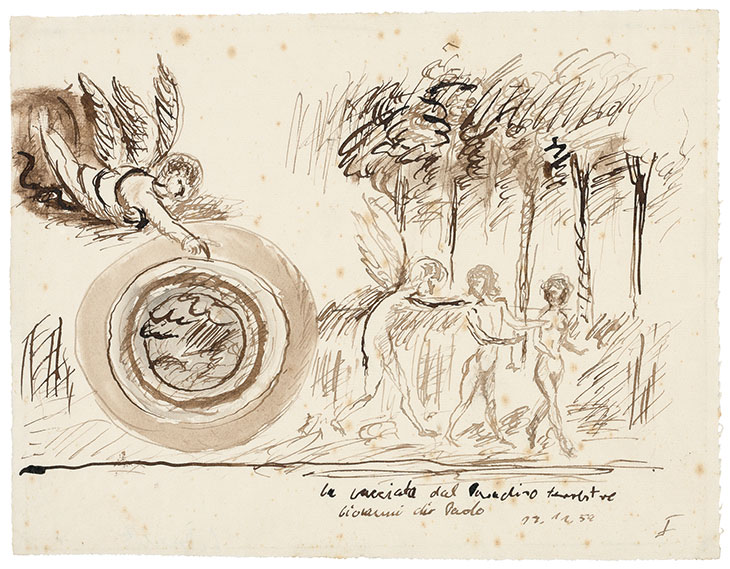

It was no surprise to learn, speaking to Baselitz one wet Saturday in Venice before the Biennale opened, that he had selected the exhibition himself, together with the curator Kosme de Barañano. The earliest works are a small selection of drawings made after Italian Old Masters: Giovanni di Paolo, Rosso Fiorentino and Pontormo. Growing up during the war and the time of post-war reconstruction, Baselitz did not see originals of these, or of anything much else, until the Berlin museum collection was returned from Russia in 1958 (when Baselitz was 20). The sense of loss and sudden revelation made a deep impression – he often works in ‘homage’ mode, creating personal bridges with past masters. Two canvases from his most recent series, Devotion, bring this up to date — small inverted portraits, sketchy faces illuminated as if with cosmic dust, showing artists both past and present, from Edvard Munch to Tracey Emin.

Ohne Titel (La cacciata del Paradiso terrestre – Giovanni di Paolo) (Untitled (La cacciata del Paradiso terrestre – Giovanni di Paolo); 1959), Georg Baselitz. Photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin; © Georg Baselitz

The link with Venice might seem a little tenuous. As the student drawings show, Baselitz’s first passion was for the linear style of further south, one that fed into the extraordinary prints and paintings that he made for his Heroes series: harried figures wandering in battle-scarred landscapes, first hatched around the time of a scholarship at the Villa Romana in Florence in 1965. It was in Florence also that he came across a photobook of the Venetian woodcarver Francesco Pianta’s extraordinary ornate carvings in the Scuola Grande di San Rocco, and made a series of drawings based on the images – although did not at the time go and see the originals. Venetian painting, meanwhile, held little interest, and still doesn’t. There’s no such thing, he says, at least in his own mind — Carpaccio, perhaps, but after that not much. Titian made some good portraits, but the rest is of little interest. In the Scuola, when he finally visited, Baselitz’s eyes would have been firmly fixed on Pianta’s carvings below, rather than Tintoretto’s grand paintings above.

In fact, this exhibition seems less about exploring a bridge to an Old Master past than of showing how Baselitz now relates to his work made some 50 years ago — how the contemporary Baselitz relates to the ‘art history’ Baselitz. Following the Heroes paintings and student riffs on Old Masters (which are hardly copies, but very loose interpretations), displayed at the Accademia are two groups of portraits and figure paintings, the latter mostly inverted images of Baselitz and his wife Elke. They are all paintings that Baselitz suggests were underappreciated at the time, rejected, in particular by certain American critics, as being the sort of painting that was just no longer possible. All people wanted to know (and still do, for that matter), was which way up they were painted.

Schlafzimmer (Bedroom; 1975), Georg Baselitz. Georg Baselitz Treuhandstiftung. Photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin; © Georg Baselitz

This parti pris becomes only clearer in the final gallery, where a wooden sculpture of a head on a plinth (Kopf, 1979/84) brings to mind Baselitz’s scandalous display with Anselm Kiefer in the German Pavilion at the 1980 Venice Biennale. Baselitz’s contribution – his Modell für eine Skulptur, a recumbent wooden figure raising his arm in what was taken by less imaginative critics as an allusion to the sieg heil salute – provoked uproar. Baselitz sat with his friend, the Venetian painter Emilio Vedova (their friendship is attested by an exhibition selected by Baselitz, currently on display at the Fondazione Vedova), and watched the German television news coverage at the time – the camera tracking into the pavilion, closing onto Baselitz’s sculpture, playing the Horst Wessel Lied, a famous Nazi anthem. Joseph Beuys, who had exhibited at the Pavilion two years earlier to great acclaim, visited during the press view, and was heard on leaving to say ‘not even first semester’, Baselitz recalls.

How much, I ask Baselitz, do you feel you have in common with the younger artist who made the copies after Giovanni di Paolo, kicked up a fuss with the Pandemonium manifesto, and created the Heroes? Baselitz is clear on this – ‘I am one and the same person’. The sense of continuity is impressive. I ask him whether he ever doubts himself. Not really, Baselitz answers – when he paints he doubts nothing, although when he walks out through the studio door all that begins to change.

Der neue Typ (The New Type; 1966), Georg Baselitz. Photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin; © Georg Baselitz

The truth is that you feel Baselitz’s doubt throughout. The doubt of a self-professed outsider, one who describes himself as ‘vollständig stupid’ (‘completely stupid’), and who likes to provoke with his often deliberately contrarian views, but who also remains acutely aware of what makes a good painting. His affinities are with those who make art out of brute need, regardless of quality, and it is no surprise to learn that his earliest memory of seeing a painting was of Munch’s Madonna reproduced on a calendar above his father’s desk in Dresden during the war. His first drawings on leaving the Academy of Art in East Berlin more than a decade later were attempts to draw like Munch, he continues – all of which have sadly been lost.

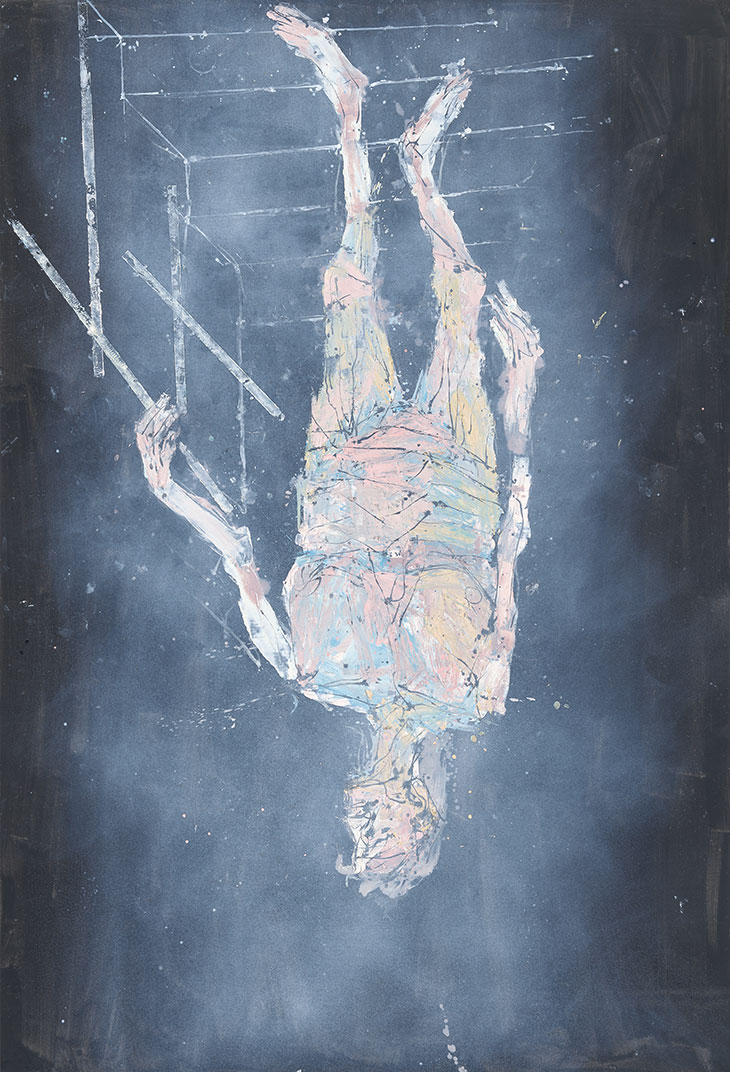

The ‘seething in the belly’, as he once put it – the anger of being a young artist cut off from the past, is also still there. Two very large canvases at the Accademia, painted for this exhibition, show ghostly upside-down figures walking down staircases, like apparitions in the night sky. They are inverted homages to ‘the painter I most hate’, Baselitz says: Marcel Duchamp. He is ‘terrible’ at painting, a ‘mere copycat of Picasso’. His Nude Descending the Staircase, No. 2, was rejected by artists when it was first shown in Paris in 1912, Baselitz adds, yet everyone ended up riffing on it, notably Gerhard Richter in a blurred photo-painting of his wife descending a staircase. (When he first saw them at a group exhibition at the Haus am Waldsee in 1964, Baselitz found Richter’s photo paintings ‘embarrassingly bad’ – trying and failing to paint like Warhol, in his view.) It is more bloody-mindedness from Baselitz, and yet the resulting works, both titled Ankunft (Arrival), are strangely moving (although my hopeful suggestion that the formless painting of the bodies, as if made from light, echoes the body of Christ in Titian’s Pietà, upstairs in the Accademia, falls on fallow ground). The obvious interpretation is that they are paintings about death, about a heavenly arrival, and that they follow from his earlier double portraits with Elke. Few artists have painted married life with such consistency and such a lack of emotion or enquiry into what marriage might mean, apart from the simple continuity of togetherness.

Ankunft (Arrival; 2018), Georg Baselitz. Photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin; © Georg Baselitz

The lack of emotion is expressed with a coldness on which Baselitz is keen to expand. ‘It’s never cold enough’, he comments, referring not only to the latest paintings, but also to a series from 2012, the Negative Pictures, made with a splashy light line and strokes on a black background. The coldness, it seems, comes with the need for images in which the subject is always dissolved, lost to the simple needs of good painting – colour, line and composition. Baselitz tells me that he never paints from life – Elke has never modelled for him, despite the realistic appearance of many of the early upside-down portraits. Perhaps his desire for detachment also explains his aversion to the dark heat of Venetian painting; red is perhaps the colour he has used the least. The connection might rather be with Antonio Canova, whose grand cold surfaces can be seen just along the corridor from Baselitz’s works in the Accademia. It is a connection he likes, although he laughs when recalling Canova’s vast pyramidical tomb in the Frari – the sort of thing Mussolini or Franco might have preferred, he adds. And it is true that, despite the grand size of many of Baselitz’s recent paintings, the sense of the image is always on a smaller, somehow deflated scale – as artless as Baselitz wants it to be, but also as movingly personal.

‘Baselitz – Academy’ is at the Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice, until 8 September.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?