From the June 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In 1970, the Museum of Modern Art in New York opened a blockbuster exhibition, the preparations for which had involved numerous scholars, several millionaires and some clandestine diplomatic negotiations to secure loans of works held in Russia. Three years earlier, after the death of Alice B. Toklas – partner of the writer, collector and salonnière Gertrude Stein – a group of the museum’s trustees had acquired a cache of the masterpieces that had lined the pair’s walls for 60 years. To celebrate the purchase, they launched a monumental undertaking: to reunite as many as possible of the works once owned by Gertrude, Leo, Michael and Sarah Stein – one of the most influential collecting families of the 20th century. Curators pored over faded photographs of their Paris apartments, identifying pictures and sleuthing to discover their current whereabouts. Eventually they gathered more than 200 artworks, now spread across the globe: masterpieces by acknowledged 19th-century greats (Manet, Bonnard and Renoir), Surrealist canvases by the cosmopolitan ‘Neo-Romantics’ (Pavel Tchelitchew, Eugène Berman, Christian Bérard) and Cubist compositions by Pablo Picasso and Jean Gris. Among them was Cézanne’s still life of a bowl of apples, which Leo had taken with him when he left the flat he shared with his sister for a new life in Florence. For the first time, it was united with Pomme (Apple), which Picasso had painted to console Gertrude for the absence of her favourite Cézanne. An inscription on the back of this canvas read ‘Souvenir pour Gertrude et Alice, Picasso, Noel 1914’.

If only the artworks in the Stein collection could talk. From the walls of 27 rue de Fleurus, they presided over salons where an international array of writers and artists mingled on equal terms and inspired a ferment of creative innovation which resonated down the decades. Gertrude and Leo Stein bought their first paintings from Ambroise Vollard’s shop on the rue Laffitte, shortly after they arrived in Paris from America in 1903. Leo was studying painting, Gertrude was determined to write; at first, buying art was a diverting way to decorate their new home and spend the monthly allowance they received from their brother Michael’s shrewd investment of funds acquired by selling an idea for a railway franchise to a San Francisco transport mogul. Since works by established masters were out of their price range, they focused on newer names, willing to take risks on art that appeared daring, strange, or even ugly. At the Salon d’Automne of October 1905, they bought Matisse’s Femme au Chapeau, to the surprise of the artist, who had considered burning the painting for the insurance money after witnessing the crowds jeering and scratching at the unfamiliar daubs of pink, purple, blue and green. Michael and his wife Sarah became Matisse’s primary patrons, but Gertrude’s attentions were soon diverted. A few weeks later, she and Leo visited the gallerist – and former clown – Clovis Sagot, who offered them a new work by a young Spanish artist he insisted was ‘the real thing’. When Gertrude confessed she didn’t like the legs, Sagot offered to guillotine the canvas in half; Leo convinced her to take the full painting, and they bought Picasso’s Girl With a Basket of Flowers for the equivalent of $30. It last sold, in 2018, for $115 million.

Madame Cézanne with a Fan (1878/88), Paul Cézanne. Emil Bührle Collection, on long-term loan at Kunsthaus Zürich

The Steins’ Left Bank apartment was, in a sense, the first museum of modern art. Word quickly got out that these eccentric American siblings opened their doors each Saturday night to anyone who wanted to see their collection of works by vanguard contemporary artists making radical experiments with form: many visitors were deeply affected by what they saw. Leo Stein remembered Picasso staring so intently at Cézanne’s portrait of his wife, hung above Gertrude’s desk, that he feared the painting would dissolve under the scrutiny: the artist later attributed to Cézanne’s example some of the aesthetic breakthroughs that led to the origins of Cubism (Gertrude, too, revealed that Cézanne’s approach to space and form had been a formative influence on her writing). Even those who didn’t visit the salon in person were affected by its power: the Steins lent paintings to the Armory Show in New York, the first exhibition to introduce modern European art to American audiences; Roger Fry borrowed several works for the Post-Impressionist exhibition he curated at London’s Grafton Galleries in 1910, which set Virginia Woolf thinking about new ways of representing people, to prioritise expressiveness of inner realities over achieving a likeness. Gertrude Stein ‘used the pictures every minute of the day’, as Toklas put it: her physical immersion in cutting-edge art inspired her own extraordinary experiments with language, venturing – in the words of one contemporary critic – to ‘do with words what Picasso does with paint’.

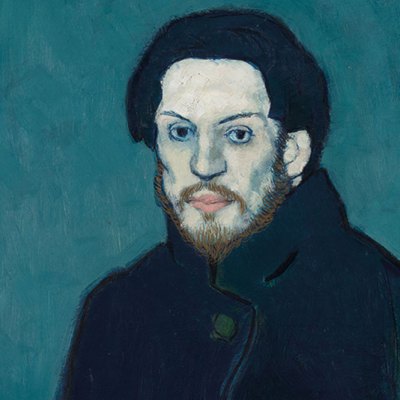

Down the years, the Stein collection underwent regular transformations. Paintings Gertrude had fallen out of love with – or whose creators had displeased her – were consigned to a back room they called the ‘salon des refusés’, while her own portrait by Picasso was always hung most prominently, placed above her chair. She was not averse to deepening rivalries between artists by repositioning works: Picasso painted Les Demoiselles d’Avignon in a jealous rage after arriving at the rue de Fleurus to find Matisse installing his latest production, Bonheur de Vivre, above the dining table. Leo left the household in 1913, taking with him all the Matisses (Gertrude, who had begun to suspect Matisse’s art was decorative rather than revolutionary, kept the Picassos). For the rest of her life, Gertrude traded artworks with friends and dealers whenever she needed money – for food supplies in the two world wars, or to raise funds for the publishing house she and Toklas established, in 1930, exclusively to print her own avant-garde writing. She continued to collect after Leo left, though some murmured that she had lost her touch: time may have vindicated her support of Francis Picabia, but few understood her ardent championing of Francis Rose, an opium-smoking, self-mythologising Scottish baronet whom Toklas commissioned to design Stein’s tombstone. (It may be time for a reappraisal: his sketches of Stein and Toklas at home are delightful and many of his Surrealist-inflected paintings are intriguing and accomplished.)

Gertrude Stein in her apartment in Paris in the 1930s, sitting beneath Picasso’s portrait of her. Just visible on the other side of the chimney is the painting Madame Cézanne with a Fan. Photo: Bettmann/Getty Images

By Gertrude’s death in 1946, the collection was diminished; in 1963 the remaining works were sequestered by her heirs, anxious that the elderly, frail Toklas – who was prone to leaving the apartment for months on end to attend arthritis cures in Rome – was not properly safeguarding their inheritance. Now that they’re dispersed in air-conditioned museums across the world, it’s easy to forget that these paintings spent much of their lives in the intimacy of a home: forming a backdrop to everyday goings-on, soaking up cigarette smoke, accumulating layers of grime dislodged only by the occasional feather duster. (They were reunited again at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2011; the catalogue of that show contains a wealth of fascinating information.) Yet every work once owned by the Steins bears within it the vestiges of its one-time home – and the proud mark of its collectors’ taste. ‘It was a collection,’ wrote Janet Flanner in the New Yorker, ‘with its own kind of private life.’

From the June 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.