From the June 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Goodwood’s new Art Foundation is nothing if not ambitious. Its catalyst was in part the closure in 2020 of the Cass Sculpture Foundation, a charity which had for nearly 30 years rented 26 acres of this historic Sussex estate for the commissioning and display of contemporary British sculpture. But it has also been a long-held desire of the current Duke of Richmond to set up a major not-for-profit at Goodwood and, as he told me a few weeks before the foundation’s opening, to ‘do something with contemporary art’.

This may come as a surprise to those who know Goodwood for its horse racing and motorsports, and the Duke as the founder of the hugely successful Festival of Speed and the Goodwood Revival. Yet Charles Henry Gordon-Lennox, 11th Duke of Richmond and Gordon, to give him (almost) his full title, is also a respected fine art photographer. As a collector of Surrealist and post-war photography, he has made what he describes as a very modest contribution to the family collection, but he wanted to go further to bring art at Goodwood up to date. Most of the collection at the house belongs to the 17th and 18th centuries – the heyday of the family’s fortunes – with paintings commissioned from Canaletto and George Stubbs among the highlights, as well as 18th-century French decorative arts. The remit of the new foundation involves bringing to the estate some of the best contemporary art in the world, in all media.

Goodwood House remains a family home, although its state rooms are open to the public. As we sit talking in its fine, flower-filled Large Library after a tour of the foundation’s grounds, now expanded beyond the original Cass site to embrace an ancient woodland and some 70 acres, the as yet unpainted cement slabs of a monumental Hélio Oiticica installation are being prepared to weather the British climate. The Invention of Colour: Magic Square #3 (1977–79/2025) will be the first outdoor sculpture by this influential Brazilian artist in Europe. Oiticica made interactive installations called penetráveis (‘penetrables’) throughout the 1960s and ’70s – the most famous, Tropicália, giving its name to the movement of art, music and Brazilian identity. This brilliantly hued piece, one of three works in his celebrated Magic Square series, will lure visitors inside, an invitation to enter and explore a labyrinthine art space.

Pale-Pink Pineapple/Bomb (2025), a painted bronze sculpture by Rose Wylie. Photo: Adam Firman; © Rose Wylie

Rose Wylie’s whimsical painted bronze Pale-Pink Pineapple/Bomb (2025) had arrived from the foundry the day before my visit and been installed on a sight line leading to the distant shimmering sea. Residing nearby were the interlocking forms of Octetra (three element stack) (1968/2021), designed as a play sculpture by Isamu Noguchi. Dame Rachel Whiteread’s new and yet-to-be unveiled monumental staircase piece, Down and Up, had not yet been delivered. Nor had Detached II (2012), another concrete work cast this time from a humble garden shed. Part of her ongoing series of Shy Sculptures, it is to be secluded in the ancient woodland and slowly age, like its original counterpart, to merge into its environment. Destined for a woodland glade is a pair of white-painted bronze slabs reminiscent of tombstones or memorials. For Goodwood’s opening exhibition on Whiteread, they will be joined by Doppelgänger (2022–21) in the Gallery alongside her outdoor photography, a little-known facet of her work.

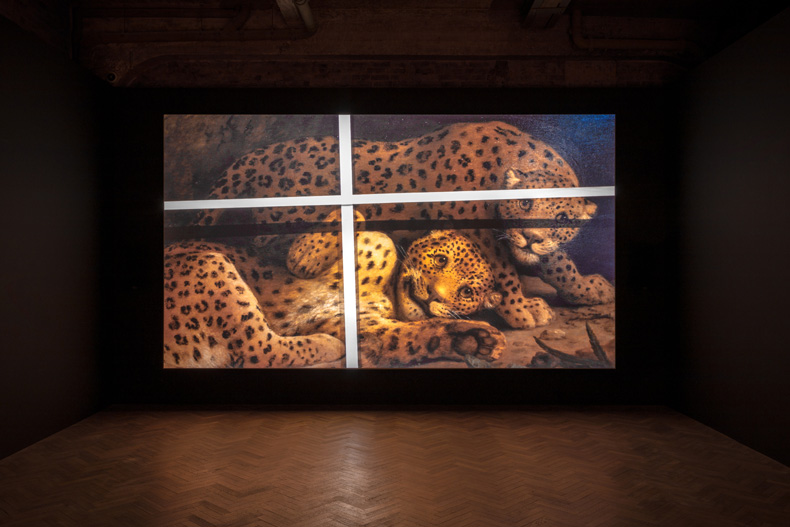

Other Turner Prize winners will also take a bow. New sculptures by Montserrat-born British artist Veronica Ryan, Magnolia Blossoms and Magnolia Pod, refer to Goodwood’s newly planted magnolia grove. A sound sculpture by the Berlin-based Scottish artist Susan Philipsz will be installed in the ancient woodland: four singing voices emerge from the trees in As Many as Will (2015), an immersive vocal work whose shifting rhythms, based on 17th-century country dances, bid visitors to join in. In the smaller Piggott Gallery, an expansive film installation by the American artist Amie Siegel, Bloodlines (2022), and her print series Cloudes (2023) both refer to paintings in Goodwood House by George Stubbs, whose career as a sporting artist and animal painter was launched by the patronage of the 3rd Duke of Richmond.

Even without most of the works of art in place, much of the new planting barely established and the site a hive of activity of men and women in high-vis and hard hats, the magic – and the potential – of the place is self-evident. Part of the charm lies in its seclusion, hidden as it is behind a high flint wall built by prisoners held in Portsmouth during the Napoleonic Wars. Almost every long vista down to the distant sea is framed by trees. This particularity is complemented by similarly distinctive programming. Deftly led by the foundation’s consultant curator, Ann Gallagher, previously head of the collections of British art at the Tate, it brings together artists of international renown whose work either has a particular affinity with the natural world or is a response to the specific landscape or history of Goodwood. The works themselves are accessible to all. As Richard Grindy, the director of Goodwood Art Foundation, puts it, ‘What we really want is to be engaging a public who may otherwise not feel comfortable about visiting a museum in a city, or taking their children where they are not sure how to conduct themselves. We asked ourselves, “How can we make it as easy as possible to engage with some of the best art in the world?”’

Untitled (Magnolia Pod) (2024), a bronze by Veronica Ryan that chimes with the new magnolia grove at Goodwood. Photo: Lucy Dawkins; courtesy Goodwood Art Foundation; © Veronica Ryan

Some of these loaned works will remain in situ for several years; others will come and go. Each is carefully positioned in a particular but subtly changing natural environment that purposely retains a wild aesthetic – woodland, plantation, wetland and meadow rather than the usual swathes of manicured lawn. Sculpture is not used as costume jewellery. It is there to be discovered, and by the widest of audiences. As the Duke says, ‘We want to make a significant addition to the contemporary art world if we can, providing something that people will find exciting and different and a special experience, while at the same time being grass-roots useful to our local community and those who need it the most.’ He continues: ‘I am a real believer that if you present people with the best in the world – whether they know what the best in the world is or not is irrelevant – there is always an excitement and frisson around it.’

He is also a believer in finding the right people to drive a vision forward and giving them their head. Art, Environment and Education are the three pillars here, all mutually dependent. ‘We worked out pretty quickly that we wanted to work with the best in the business, and were lucky we found the team very quickly,’ the Duke adds. Grindy, responsible for the business and operational side of the project, came aboard as a consultant seven years ago. Gallagher followed shortly thereafter, as did the horticulturist and landscape designer Dan Pearson. Pearson’s intuitive, naturalistic and sustainable approach is recognised for its sensitivity to place, and the success of the interaction between art and environment ultimately depends on this collaboration between artist, curator and designer. Pearson’s ingenious planting scheme promises 24 seasonal moments – that, is something new to see or smell – throughout the year (one every two weeks). Each space has its moment of glory. Swathes of snowdrops, hellebores, a bluebell wood, groves of magnolia and cherry, Swedish whitebeam and a katsura grove – where coppery leaves dropping in autumn smell like burning sugar – headline a programme that is designed to encourage return visits. Meandering paths and routes between the works, the two gallery spaces and a new cafe, 24, also provide sanctuaries for rest and contemplation.

A thousand trees and some 100,000 bulbs have been planted. To allow in light for these woodland glades, a couple of hundred trees that were either failing or non-native were felled and repurposed as log-stack walls, wood-chip paths or fuel for the estate’s biomass boiler. Hidden among the trees is a giant wigwam, the Learning Hub. The discreet steel, timber and glass visitor gallery built for Wilfred and Jeannette Cass has been refurbished and adapted as the Gallery, while the former archive and library building provides the second exhibition venue. Both buildings were designed by the architect Craig Downie, who has returned to design the striking, asymmetrical cafe with its generous dining terrace projecting into the landscape. Even inside these spaces, the woodland is a constant presence.

The Pavilion at Goodwood, designed by Studio Downie Architects. Photo: Tom Baigent; courtesy Studio Downie Architects LLP

This is a bold and costly project, which became bolder and costlier as it unfolded. In launching the foundation, the Duke admits that ‘we jumped off the cliff a bit – Goodwood did have to get behind it at the beginning’. Getting behind it included funding and constructing the Oiticica installation, a major logistical challenge, and serious fundraising. Despite the Duke’s reputation for working 12-hour days and for meticulousness, it was clear that Goodwood could not fund it all itself: ‘We employ 700 people here. It is a huge pull on our capital just to keep the place going.’ The family and the Goodwood team are old hands at raising money for all kinds of charities. Donors not only stepped up to the plate, but also encouraged the foundation to aim higher. One of those was Stephen A. Schwarzman, co-founder and CEO of the global private equity firm Blackstone, whose foundation has paid for the landscaping. Rolls-Royce, whose headquarters, design, manufacturing and assembly centre is on the Goodwood estate, is sponsoring the Whiteread exhibition and is committed to supporting the foundation’s main annual exhibition for three years. Founding patrons have similarly committed to an initial three-year arrangement.

For the Duke, ‘the real payback’ from the foundation will come from its third pillar: education. In a sense, this programme is building on an established legacy. His father created an education trust in 1976 and set up a small school on the estate to promote awareness and understanding of the natural environment and sustainable agriculture among children and young people, particularly those who are disadvantaged or have special educational needs. Already, around 3,500 children a year visit the organic Home Farm or the Forest School on the estate. To this, the art foundation adds a creative learning programme devised by Sally Bacon, which focuses on personal development and well-being. Transport is free for schools or groups without the resources to pay and there are art backpacks to take away.

For Goodwood’s current proprietor, the scheme has a particular resonance. ‘We hope it will be useful to people who need it the most – children who are excluded from school, children who would not normally be taken to see art. We hope it may be transformative in some way.’ The Duke pauses. ‘I was obviously super-fortunate as a child, but I hated every school I went to, pretty much. Only one school, which I went to for two years, introduced me to everything that I am interested in now, and that was because a master who taught photography took some interest and gave me encouragement. You only have to show kids a tiny bit of interest and they blossom.’ He continues: ‘There is very little art or music on the national curriculum now. Not to get that is shocking. If we get it right at Goodwood, we can have some impact.’ Music is part of the programming for open-air events and performances in the amphitheatre, created in a clearing in the woods. A gallery performance space is on the agenda for phase three.

Bloodlines (2022), a film by Amie Siegel, is on display in Goodwood’s Piggott Gallery. Photo: Richard Ivey; courtesy the artist/Thomas Dane Gallery; © Amie Siegel

Phase two of the landscape development will focus on greater biodiversity, with a lake and large wildflower meadows under discussion. The Duke sees no conflict in offering the thunder of high-octane motor-racing or the roar of Spitfires on one part of the estate and a sanctuary for the calm contemplation of art and nature and the encouragement of wildlife and native species on another. ‘Why can’t we love racing and cars – we run all cars on sustainable fuel now anyway – and organic farming and food?’ he asks me, perhaps slightly defensively. ‘My mother was passionate about the environment and so is my wife. Our farm went organic thirty years ago.’ Their approach to farming as well as landscape is sensitive to the environment. Estate-produced organic meat and cheese is served in Goodwood’s restaurants and at events, and foraged food will also be on the menu at 24. ‘The idea of eating the place is another important part of Goodwood,’ he smiles, equilibrium regained.

The Duke describes himself as involved in everything that goes on at Goodwood but ‘very, very, very involved’ in the visitor experience. ‘I mind how things look and feel, and I am pushing all the time for even the smallest detail to be right. We want people to have their own particular experience, and what feels like a private experience. How you deliver that is an interesting question.’ One answer is to manage visitor numbers by charging adults £15. ‘The revenue driven by attendance does not make much difference, but we don’t want huge numbers as we don’t want it to be crowded.’ His mantra has always been that everyone has access to everything: ‘No exclusions, no restrictions about getting close to things, no ropes.’

Detached II (2012), a concrete work by Rachel Whiteread cast from a garden shed, which is designed to merge into its surroundings over time. Photo: Lucy Dawkins; courtesy Goodwood Art Foundation; © Rachel Whiteread

‘Right now,’ he says, ‘the exciting part of the project for me is the art. It is a bit like when we started the Festival of Speed. The real challenge was how we were going to bring cars that no one had ever seen here. For the foundation, it is who can we entice here.’ When I ask Rachel Whiteread how she was enticed, she says: ‘Ann asked me. We have worked together a lot, and I trust her.’ Trust, then, and attention to detail. ‘It was important to work with the landscape, which did not really exist at the beginning,’ she continues. ‘Ann and I have been backwards and forwards here for a couple of years.’

Both the Duke and Ann Gallagher feel that the programming needed continuity. Gallagher is committed to five years at Goodwood. The next season is lined up and there is already a good idea of the foundation’s subsequent, year-round programmes. As for the family, ‘We have been here a long time and intend to be here a long time,’ the Duke says. ‘This is a long-term project and a long-term legacy.’

Goodwood Art Foundation at Goodwood, Chichester is now open.

From the June 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.