On my way to Günther Uecker’s (b. 1930) studio in Düsseldorf, I manage to lose my way, and when I ask for directions a helpful passerby points past a twisting trio of Frank Gehry buildings and says, ‘Take a right at Uecker Platz.’ Günther Uecker may have the honour of having a whole square christened after him, but he’s not a grand figure. When I finally get to the studio, the artist himself greets me at the door of his huge, two-storey converted warehouse on the banks of the Rhine. (Uecker has been based here since 1987, when he moved out of the space he used to share with Gerhard Richter.) He is instantly recognisable from the slew of recent publications that chart the happenings of the 1960s and in which he invariably appears wearing overalls, with close-cropped hair – often pictured with other avant-garde luminaries such as Yayoi Kusama, or John Cage, or staring intently into the camera of Lothar Wolleh.

Upstairs are Uecker’s projects, which include canvases large and small as well as an array of tools, a chair covered in spikes and much stranger contraptions, such as a typewriter featuring nails for keys. Nails are the German artist’s signature material – but Uecker is more than comfortable using them for their usual purpose. ‘I built all of this,’ he says proudly, referring to the internal partition walls and columns, as well as the artworks around us. But when I ask him if he has really, as it’s sometimes said, used 100 tonnes of nails in the course of his career, he laughs at me. I walk carefully so as not to disturb the careful arrangements on the floor of his many publications and the works that document his extensive travels – he has just returned from Iran. It’s hard to take in the sheer variety of his work as, at pace, he guides me through a 60-year career marked by imaginative collaborations and constant reinvention.

Works made for the ‘Verletzte Felder’ (Wounded Fields) exhibition at Lévy Gorvy, standing in Uecker’s studio in Dusseldorf in August 2016. Photo: Herbert Koller; © 2016 Günther Uecker

In recent years, it has been for his work with the avant-garde ZERO group for which Uecker has attracted the most attention. In Germany he has had regular showings at the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin, most recently in 2015, and his work features in the ZERO exhibition at the LVR-LandesMuseum Bonn (until 26 March). He has also taken part in major exhibitions at US museums, most notably in the comprehensive ‘ZERO: Countdown to Tomorrow, 1950s–60s’ at New York’s Guggenheim in 2014. These have sought to map the network of relationships that characterised contemporary practice in the post-war period, placing ZERO firmly in the centre of things and redrawing the mental map of the art world in the process.

ZERO, the movement with which Uecker is most closely associated, has always been hard to classify. It began with a pair of Düsseldorf artists – Heinz Mack and Otto Piene (Uecker would join a little later) but grew into a sprawling intercontinental movement that reads like a Who’s Who of the post-war avant-garde; it drew in everyone from Yves Klein, Jean Tinguely, Lucio Fontana, and Piero Manzoni, to Yayoi Kusama and the Gutai group. More confusing still, many of its members are known for their involvement with other movements, which have already taken their place within the pantheon of modern art – minimalism, Nouveau Realism, Arte Povera, Op Art, and Land Art.

Despite this complexity, the recent scholarly attention paid to the group has also led to interest from the international art market: a 2010 sale of works by ZERO artists at Sotheby’s, London set 19 auction records, while at Art Basel in 2014, a group of eight white paintings by Uecker sold for more than five million euros to a European foundation. In 2016 Uecker had his first London show in 50 years, ‘Günther Uecker: Verletzte Felder (Wounded Fields)’, at Lévy Gorvy.

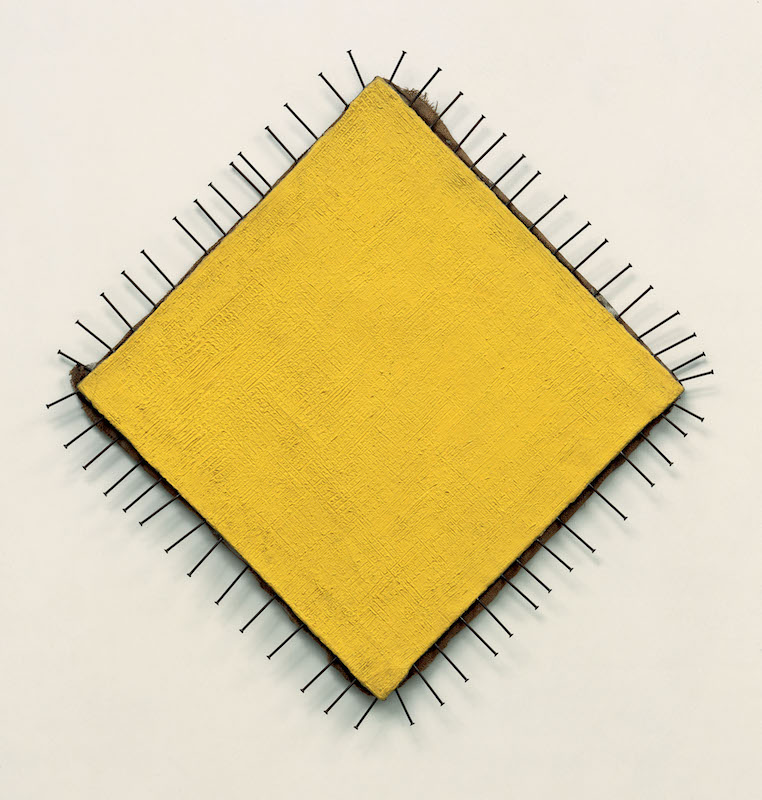

Das gelbe Bild (1957), Gunther Uecker (b. 1930). Courtesy Archiv Uecker

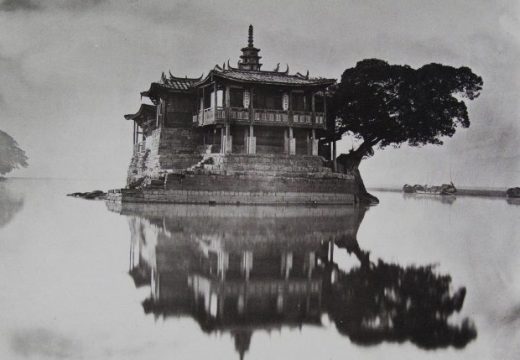

The fields in the London exhibition’s title are an apt description for Uecker’s oeuvre, since he often creates surfaces from which nails sprout like wheat, casting intricate patterns of shadows with their battered heads. Pointing to a canvas covered in welt-like patches of nails and leaning against a wall, he says, ‘These are like the marks you have from injuries…scars.’ The roots of this strange crop, Uecker explains, lie in the fertile soil of his childhood in Fischland (literally ‘fish land’), a narrow spit of land between the Baltic and a chain of shallow, brackish lagoons that shadow the coast in the north of Mecklenburg. Uecker says, ‘The inspiration for my work comes from nature – my father was a farmer and I still believe our purpose in life is to bring the fruit from the earth.’

During the war, the town of Wustrow in Fischland became a testing ground for the Luftwaffe. ‘I remember the smell of all the lacquer and other materials for the aeroplanes, and on the other hand the ground, the smell of the earth and the animals we had. It was a wonderful combination of contrasts,’ Uecker says. Some of his memories of that time are much grimmer. In May 1945, just days before the German surrender, the prison ship Cap Arcona with 5,000 people on board was sunk by British bombers. ‘Bodies from the ships washed up on the coast, and were left there splayed out, rotting on the beach. They were mostly prisoners from the concentration camps,’ he says, tracing stripes with his fingers across his torso. ‘The Russians soldiers came and made me and two other boys bury them. They were like mummies after months in the sun.’ The grim task proved a moment of awakening for the young German. ‘I became more sensitive, to possess an empathy for those losing their lives, and so I became determined to live life with intensity.’

Günther Uecker working on a painting in his studio in Dusseldorf, August 2016. Photo: Herbert Koller; © 2016 Günther Uecker

After the war, Uecker’s family’s farmland was appropriated under the GDR regime and the young (now) East German trained as a propaganda artist until 1953, when he moved to West Berlin after the June Uprising. There he studied painting at the art school in Berlin-Weißensee. In 1955, after being interrogated and processed through a refugee camp for juvenile male refugees from the GDR, Uecker moved to the Rhineland to study. Düsseldorf was an apt choice for the aspiring artist: the city has been in the grip of the arts ever since the 1690s, when the Elector Palatine, Duke Johann Wilhelm II, built a gallery to placate his homesick Florentine wife, Anna Maria Luisa – the last Medici. Meanwhile, the Staatliche Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, where Paul Klee taught in the 1930s, remains one of the most revered art schools in Europe.

By the time Uecker enrolled at the Akademie, the city was beginning to recover some of its Weimar verve. While Uecker studied under his idol, the Communist and former condemned degenerate artist Otto Pankok, his classmates at the Akademie included Joseph Beuys and Günter Grass (whose 1959 masterpiece the Tin Drum evokes the spirit of the city at this time). As Uecker says, ‘Düsseldorf was not Prussian like Berlin – Protestant and fascistic. It was near to the West, to Paris, Amsterdam, and Antwerp. It felt to me as though I were passing over the Limes Germanicus, the border the Romans built on the Rhine, away from the dark woods and into civilisation.’ In 1956–57 Uecker created his first nail paintings, Malereiumnagelung and Das gelbe Bild, when he began to ‘over-nail’ painting he had been working on. ‘Coming from East Germany, where I had been educated about the Russian Revolution of 1917, I was thinking about Vladimir Mayakovsky’s declaration that “poetry is made with a hammer”.’

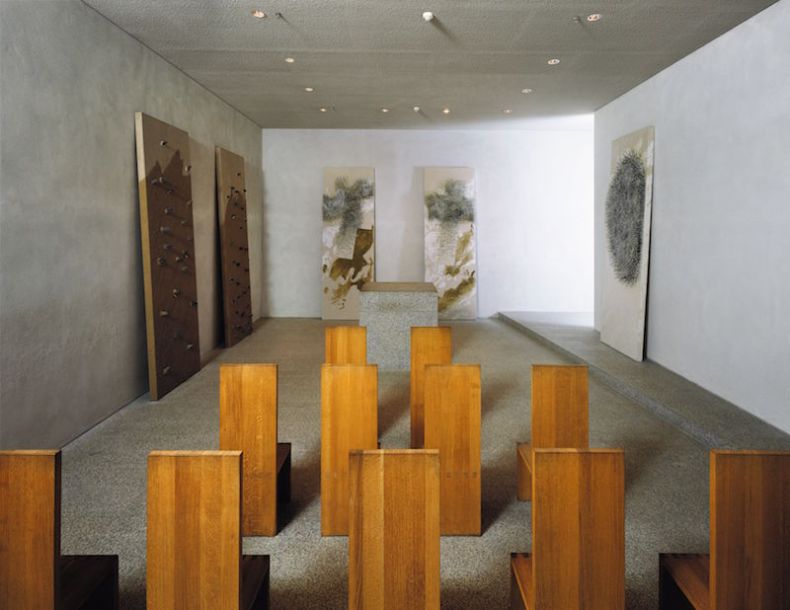

The prayer room at the Reichstag, designed by Günther Uecker in 1998–99. Photo: Nic Tenwiggenhom

In the same year, two former students of the Akademie, Heinz Mack and Otto Piene, decided to hold a series of exhibitions of their own work in their studio and began to invite other artists to exhibit alongside them. Yves Klein, who was showing ‘Yves, Propositions monochromes’ at the Schmela Galerie in the city, quickly became involved. ‘ZERO’, the name Mack and Piene chose for their burgeoning collective, was inspired by the countdown to a rocket launch and reflected the group’s fascination with technology and with kinetic art. It also hinted at rebirth, 1945, after all, was commonly described as Stunde Null, Germany’s ‘zero hour’.

Piene, Mack, and Klein published the magazine ZERO 1 in April 1958 and by October of that year, a group of seven or eight affiliated artists exhibited and published ZERO 2. ‘In 1958, Mack invited me to the first exhibition “Das Rote Bild”, as he did Klein and Fontana,’ says Uecker of the casual way in which the group grew. Uecker was later to take an organising role in the movement but at that point, he says, he was just like any of the other artists in the expanded network.

Klein’s advocacy of monochrome works was enthusiastically taken up not just by Mack, Piene, and Uecker but by a number of other like-minded young artists. These ZERO artists and other affiliated groups, such as the Dutch Nul and Azimuth in Italy, made paintings with fire, smoke, mirrors, dynamos, or even by destroying their canvases. Piene wrote at the time, ‘Wir sind fur alles’: we are in favour of everything. In the summer of 1958 Klein met and fell in love with Uecker’s sister, Rotraut, who went on to became his assistant, ‘living paint brush’, and eventually his wife. The match, which lasted until Klein’s premature death in 1962, proved another tie binding the Düsseldorf artists to the rest of the European avant-garde. ‘Manzoni was always in and out of my house – and Christo was actually living there,’ Uecker recalls. ‘My studio was open to all the artists, we were all very close – Tinguely too. It was an important time, and I was only 30.’

Fünf Lichtscheiben, Kosmische Vision (1961–81), Günther Uecker. Courtesy Archiv Uecker

ZERO was becoming ever more successful and Uecker’s role in the group was formalised when he was brought in to help organise their exhibition at the Stedelijk in 1961. For this Mack and Piene created their collaborative work, Salon de Lumière, a piece that channels the same fascination with light and movement evident in Uecker’s piece Fünf Lichtscheiben, Kosmische Vision (1961–81), a configuration of five rotating disks with nailed surfaces, like an interplanetary alignment. ‘Mack and Piene were teachers,’ Uecker explains, ‘and had to work in the mornings so I organised the transport and customs for the Stedelijk exhibition as well as the exhibition in San Marino [the San Marino Biennale], where we received the first prize.’

The movement continued to gather momentum and to attract more and more artists, often from places where the establishment, art-historical or otherwise, was discredited. ‘When we looked at our parents and the neighbours,’ Uecker says, ‘we thought they were all murderers, they had been responsible for the war. Young people then were very free, we felt we could do it all.’

In June 1964 Piene, Mack, and Uecker presented their collectively-realised light room, Hommage à Fontana, at Documenta 3 in Kassel. In September of that year, before a show at Howard Wise’s kinetic art gallery in New York, tensions began to surface when Mack wrote to Piene that ‘The ship zero is casting its anchor, and the voyage is over.’ Success made it increasingly difficult for Uecker, as well, to devote as much time to ZERO as he had before. In 1965 he took part in ‘The Responsive Eye’ at MoMA – a wildly succesful show credited with popularising Op Art.

I ask Uecker what he thinks about the prevailing critical view that ZERO was a reaction against Abstract Expressionism, a riposte to American cultural hegemony: ‘That’s a mere interpretation, that’s not true. Having said that, the artists in America were very nervous. Rauschenberg, for example, said: “I made a monochrome work before Yves Klein,” and I remember the New York Times described me as “This Nazi kid who looks like he has fallen down from the sky.” America was so conservative at this time, when I went over to New York, the women were all in furs and the men in black suits and ties, and polished shoes! Everyone looked like bankers.’

New York Dancer I (1965), Günther Uecker. Guggenheim Abu Dhabi. Photo: Eric and Petra Hesmerg; © Guggenheim Abu Dhabi; © Günther Uecker

ZERO came to an end with a final show in Bonn at the turn of 1966, to which Uecker contributed his piece New York Dancer I, a whirling construction consisting of a human-sized tree trunk draped with white duck cloth from which nails hung, chattering as the machine gyrated. Uecker has described it as ‘a parable for a person who feels an apparent freedom, but is turning in a circle […] I was in New York at that time, ZERO had become a success […] I had to separate myself from it to have the possibility to take risks in my life from day to day.’

Nevertheless, the artists continued to collaborate, most notably in the creation of the influential Creamcheese club, a multipurpose venue inspired by Warhol’s multimedia live performance experiment, the Exploding Plastic Inevitable. The Creamcheese opened its doors in July 1967 in Düsseldorf’s Old Town. Here Uecker and Mack staged works beside Richter and Adolf Luther, while the bar was staffed by Blinky Palermo and Katharina Sieverding. Meanwhile, an array of televisions behind the bar broadcast live images of performances held in the back by Joseph Beuys and Kraftwerk.

In 1968, at the Kunsthalle Baden-Baden, Uecker’s John Cage-inspired Terror Orchestra brought the noise of industry and machine tools into the museum. Uecker and Gerhard Richter ‘stormed’ and ‘occupied’ this same space later that year. In 1970, Uecker represented Germany at the Venice Biennale and four years later he became Professor of Free Art at the academy in Düsseldorf. Uecker has hardly been short of success, but he is still wary of its effects. ‘Don’t join the establishment,’ he says to me at one point, drumming the table for emphasis. But establishment recognition of the artist has led to some intriguing and politically charged projects. In 1998, he was chosen to design a prayer room for the Reichstag: ‘When I went to Mount Athos, I had the sense that everywhere in the world, no matter what the faith, people pray and if nobody prays in the world then we are in danger,’ he warns, before adding ‘Dann ist die welt verloren’ (then the world is lost).

Installation view at Lévy Gorvy in 2016 of Sandmuhle (1970), Günther Uecker. Courtesy Archiv Uecker

Last summer, the artist returned to where he grew up. For a piece called Wustrow Tücher (2016), he covered the beach with white shrouds, one for each burial in 1945, which he then painted. It brought to mind Sandmühle (1970), a piece he conceived while working towards the pioneering ‘Earth Art’ exhibition at Cornell University. It comprised two booms silently rotating around a central pivot in a pile of sand, each scoring the sand deeper and deeper over time. ‘Art,’ Uecker declared at the time ‘is like the traces of wounds plowed into the field.’ But despite his fixation on scars and wounding and his worries for the future, Uecker remains essentially optimistic and outward-looking. As he says, ‘The greatest danger in the world is anger.’

‘ZERO ist gut für Dich: Mack, Piene, Uecker in Bonn 1966/2016’ is at the LVR-LandesMuseum Bonn from 26 November 2016–26 March.

From the February issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?