From the June 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In his preface to One Hundred Views of Fuji, published posthumously in 1859, Utagawa Hiroshige wrote that he wanted to make ‘true-to-life landscapes’ that would ‘give others a few moments of pleasure without the inconvenience of a long journey’. More than a century and a half later, ‘Hiroshige: Artist of the Open Road’ offers a vivid demonstration of the artist’s enduring ability to transport viewers to snowy mountains, riverside picnics and rainswept hillsides. Graceful curves, comic asides and exquisite gradations of hallucinatory colour offer many pleasures along the way.

In Evening View of the Eight Scenic Spots of Kanazawa in Musashi Province (1857), one of the artist’s last works, the landscape stretches across the triptych with the ease of a sleepy cat. Boat masts echo the pine trees that line the shore in delicate rhythms, white sails chime with a moon that looms dead centre, its pale presence etched by silhouettes of birds in flight, while arches of a bridge in the lower right echo the hills and mountains in the distance. Nature and civilisation are one. With its restaurateur soliciting business from passersby and the boats hovering in the vivid blue water, Tōkaidō Autumn Moon: Restaurants at Kanagawa, Musashi Province (c. 1839) could be a scene reminiscent of a summer’s night on a Cycladic island. The work was designed to be pasted over the bamboo ribs of an uchiwa, or fan. Most would be worn out and tossed aside, but about 600 of Hiroshige’s survive, suggesting his fans were in high demand as a fashion accessory. That such a carefully made print was used for such a utilitarian purpose underlines the era’s integration of beautiful things into everyday life.

Evening View of the Eight Scenic Spots in Kanazawa in Musashi Province (1857), Utagawa Hiroshige. Collection of Alan Medaugh. Photo: © Alan Medaugh

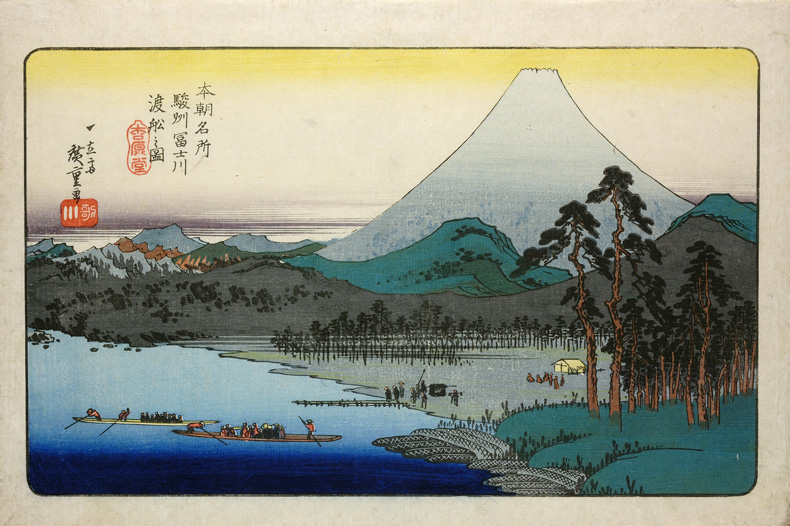

Part way through the show, a vitrine displays the tools of the printmaker’s trade – a woodblock and chisels – and the print that was made from that particular block, Ferry on the Fuji River, Suruga Province (1832). Videos and other tools nearby demonstrate how printmaking was a collective endeavour, involving the extraordinary skills of wood carver and printer, not to mention the relationship between artist and publisher.

Block-ready drawings (hanshita-e) by Hiroshige or any ukiyo-e artist were made in monochrome ink, glued to a woodblock and destroyed in the process of carving. A tripartite drawing by Hiroshige – of a crane, tit and oriole each on a blossoming branch – survives because it was never transformed into a print. It is remarkable to consider the thousands of drawings hacked up by the deft chisel of a carver, or horishi, testament to how the drawings were simply a means to an end: the print, the prized artefact.

While the prints are punchy and beautiful, their form – dynamic, angular compositions and abundant empty spaces – might be demanding for many contemporary audiences. In a gallery called ‘Nature all Around’, devoted to the artist’s kachō hanga (birds and flowers), birdsong and other nature sounds are piped into the galleries, a background din that bleeds through most of the show. It’s an absurd conceit. ‘Nature’ is such a buzzword these days, as if everyone is afraid of art. A wall text describes Arashiyama in Full Bloom (c. 1834) as ‘both realistic and inventively abstract’. Neither characterisation is helpful. The raftsmen float down the river as if on the milky way, while blossom-laden cherry trees burst like pink nebulae above a trail that snakes its way up the riverbank. Arashiyama in Full Bloom zings with playful, ecstatic joy. Hiroshige’s vistas are scarcely ‘realistic’, even compared to a landscape by a European contemporary such as Gustave Courbet.

Ferry on the Fuji River, Suruga Province (c. 1832), Utagawa Hiroshige. Photo: © Trustees of the British Museum

Instead of birdsong, not to mention a flat and unrewarding gallery devoted to artists influenced by Hiroshige, why not introduce objects from the British Museum’s excellent collection of ceramics, screen paintings and lacquerware? (The catalogue is excellent, though it too emphasises the appreciation of individual prints.) Even a wider selection of ukiyo-e by other artists would offer more insight into Japanese aesthetics or bring the broader culture to life.

Hiroshige’s work is rooted in a heightened awareness and celebration of ‘the floating world’ – the rituals of teahouses and theatres, of seasons and journeys. Yet visitors might feel adrift in a series of jewel-like impressions, isolated from a broader context. I overheard two people trying to understand why the bijin, or beautiful women, all looked identical, wondering whether they were meant to be portraits of specific people. Although I’ve lived in Japan and happened to have an inkling that tiny eyes and small mouths represent a conventional, idealised beauty not unlike the stylised lineaments of a neoclassical Aphrodite, I felt their frustration. The exhibition celebrates a gift of more than 30 prints from the collector Alan Medaugh, which might explain the emphasis on individual works. Perhaps it’s a refreshing approach in an era of moralising and pedagogical overreach. But no one benefits from hearing recorded birdsong.

Tōkaidō Autumn Moon: Restaurants at Kanagawa, Musashi Province (c. 1839), Utagawa Hiroshige. Collection of Alan Medaugh, New York. Photo: © Alan Medaugh

A generous silence reigns in the three-part print Mountains and Streams of the Kiso Road (1857). Snow-softened mountains occupy the pictorial space like fluffy pillows, their shadowy gorges lined with friendly pine trees. On the right side, the blue plunge of a waterfall frames a precarious path that hugs a ridge, above a narrow bridge, which leads into a steep trail up a ravine, each section replete with a lone traveller. On the far left, another bridge, another lone traveller. Is this the same figure that we follow through the mountains, or multiple pilgrims seeking the same destination? Either way, we fall under Hiroshige’s spell as he takes us on a journey, cozy yet perilous, evoking an immensity of space in a diminutive triptych.

Hiroshige: Artist of the Open Road is at the British Museum, London, until 7 September.

From the June 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.