Celebrating an artist’s death can seem a morbidly pious affair. Indeed in the case of Degas, who all but withdrew from the public arena in the last decades of his life, an exhibition might even be considered to be a peculiarly perverse means of paying homage to the artist in his centennial year. But it can also present the opportunity for review and reassessment, or to ‘drill down’, as Degas would have called it.

At the core of the Fitzwilliam’s centennial exhibition are the Cambridge collections: those of the museum itself, and a group of paintings and drawings acquired by the economist John Maynard Keynes at the posthumous sales of Degas’s studio and private collection in 1918 and 1919, and bequeathed to King’s College in 1946. These include a remarkable range of works: paintings, drawings, pastels, etchings, monotypes, counterproofs, bronze casts of dancers, horses and nudes, and three lifetime sculptures in wax and mixed media, the only examples in Europe outside the Musée d’Orsay.

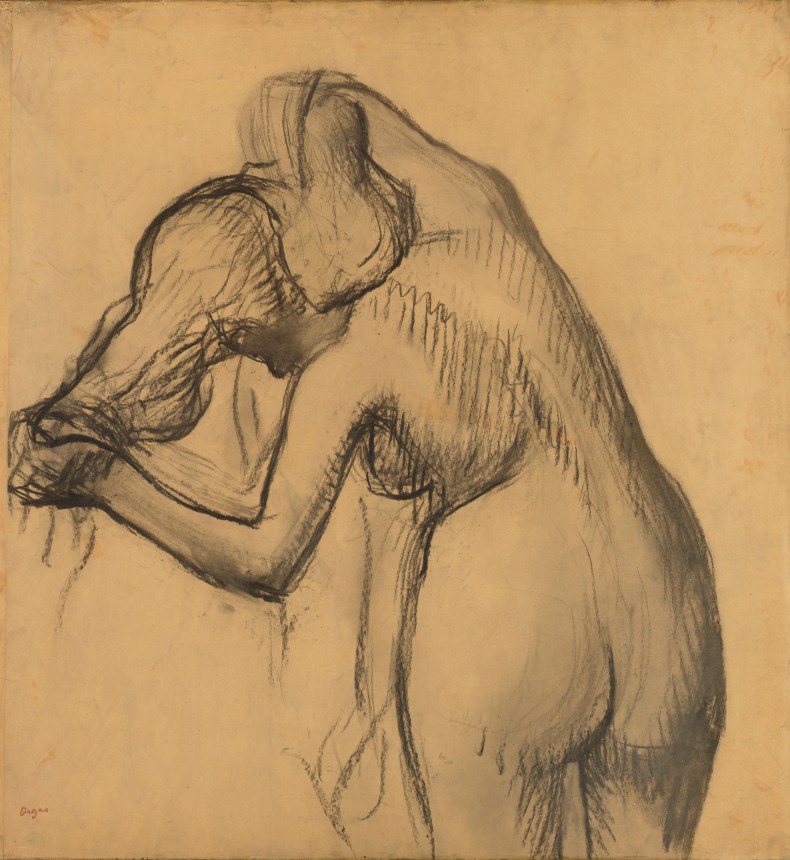

Nude Woman Drying her Hair (c. 1900), Edgar Degas. King’s College, Cambridge

Taking a distinct body of work, accumulated with the historic arbitrariness of a single collection, as a point of departure for an exhibition presents specific challenges – and rewards – for the curator. While this might limit aspirations of comprehensiveness (should such a thing ultimately be possible), it is a process which, in submitting itself to an element of the aléatoire, the randomly unpredictable, can throw up unexpected questions and connections that emerge from a close study of the works themselves. Rather than selecting exhibits to demonstrate a particular facet or period of the artist’s career, or answer a specific research question, the exercise becomes one of creating a series of interconnected ‘case studies’ that illuminate aspects of Degas’s practice and process.

The rich ‘constraints’ of the Fitzwilliam and King’s collections, the most extensive and representative in the UK across the various media in which Degas worked, have provided the springboard for a thematic approach that highlights many of the subjects most prominent in Degas’s work – dancers in performance and at rest, scenes of urban life and a lifelong fascination with the nude – but also those he treated more sporadically and idiosyncratically, notably landscape painting and printmaking. A group of 50 or so works borrowed from public and private collections internationally – some of which will be seen in public exhibition for the first time – throw the Cambridge collections into meaningful and often surprising relief.

At the Cafe (c. 1875–77), Edgar Degas. Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Take, for example, the Fitzwilliam’s enigmatic At the Café (c. 1875–77), depicting two unidentified women in hesitant conversation, seated at what we take to be a café table. Unfinished, the painting keeps us guessing. For Sickert, who saw the painting in London in 1922, it offered ‘a useful instance of a procedure of black and white dead-colour’, but comparison between the smeared, inchoate brushwork and a group of contemporary monotypes – some of his earliest experiments in ‘greasy ink’ printing – also points to aesthetic affinities that exemplify Degas’s tendency to maintain a degree of technical fluidity between the different media in which he worked. Then there is the question of identity: are these women prostitutes, as has sometimes been proposed? Or other forms of ‘working girl’ captured in a moment of café-based socialising? Arguably, and not just because their features are illegible, this matters little, for what seems to interest Degas more is the evidently tense nature of the dialogue that consumes them, but keeps them resolutely apart. Paintings and pastels borrowed for the show reveal Degas’s preoccupation with the psychological dynamics of conversation – both active and lapsed – whether between women at leisure or in more loaded scenes of gender-based inimicality in which conversation, if it ever existed, has been suspended.

Elisabeth de Valois (c. 1865–70), after Antonis Mor, Edgar Degas. Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

If there is a strand running through the exhibition, it is perhaps that of learning. Opening with a selection of works that show Degas studying and copying from artists he admired, and in some cases went on to collect – from early Renaissance artists and Dutch and Flemish masters of the 17th century to his idol, Ingres – the exhibition concludes with a section that explores Degas’s legacy among 20th- and 21st-century artists such as Sickert, Picasso, Auerbach, Bacon, Kitaj, Freud, Hodgkin, and Ryan Gander, who have drawn on Degas as he had done from artistic precedent, learning from his example while ‘doing something different’. Present throughout is evidence of Degas learning from and challenging himself, whether in the form of his multiple iterations of compositions and individual poses of dancers and nudes, obsessive reworking of paintings, sometimes to near-illegibility, or the speculative technical procedures and unconventional materials he adopted, notably to model his wax sculptures.

After Degas’s death, the temptation among his early biographers to unravel or explain the inner workings of his genius was strong. According to one, the dealer Ambroise Vollard, Degas’s decision to narrow his focus in later life and dogged reworking of a single motif was driven by his ‘passion for perfection’, as part of a wider commitment to pictorial ‘research’. A century on, his resistance to closure might equally be identified as a marker of his modernity, aligning it with the aesthetics of serialism and the non-finito, to which notions of ‘perfection’ seem alien. The exhibition presents the evidence, and leaves the visitor to decide.

‘Degas: A Passion for Perfection’ is at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, from 3 October–14 January 2018.

From the September 2017 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

How do you deal with an artist like Degas?

At the Cafe (detail), (c. 1875–77), Edgar Degas. Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Share

Celebrating an artist’s death can seem a morbidly pious affair. Indeed in the case of Degas, who all but withdrew from the public arena in the last decades of his life, an exhibition might even be considered to be a peculiarly perverse means of paying homage to the artist in his centennial year. But it can also present the opportunity for review and reassessment, or to ‘drill down’, as Degas would have called it.

At the core of the Fitzwilliam’s centennial exhibition are the Cambridge collections: those of the museum itself, and a group of paintings and drawings acquired by the economist John Maynard Keynes at the posthumous sales of Degas’s studio and private collection in 1918 and 1919, and bequeathed to King’s College in 1946. These include a remarkable range of works: paintings, drawings, pastels, etchings, monotypes, counterproofs, bronze casts of dancers, horses and nudes, and three lifetime sculptures in wax and mixed media, the only examples in Europe outside the Musée d’Orsay.

Nude Woman Drying her Hair (c. 1900), Edgar Degas. King’s College, Cambridge

Taking a distinct body of work, accumulated with the historic arbitrariness of a single collection, as a point of departure for an exhibition presents specific challenges – and rewards – for the curator. While this might limit aspirations of comprehensiveness (should such a thing ultimately be possible), it is a process which, in submitting itself to an element of the aléatoire, the randomly unpredictable, can throw up unexpected questions and connections that emerge from a close study of the works themselves. Rather than selecting exhibits to demonstrate a particular facet or period of the artist’s career, or answer a specific research question, the exercise becomes one of creating a series of interconnected ‘case studies’ that illuminate aspects of Degas’s practice and process.

The rich ‘constraints’ of the Fitzwilliam and King’s collections, the most extensive and representative in the UK across the various media in which Degas worked, have provided the springboard for a thematic approach that highlights many of the subjects most prominent in Degas’s work – dancers in performance and at rest, scenes of urban life and a lifelong fascination with the nude – but also those he treated more sporadically and idiosyncratically, notably landscape painting and printmaking. A group of 50 or so works borrowed from public and private collections internationally – some of which will be seen in public exhibition for the first time – throw the Cambridge collections into meaningful and often surprising relief.

At the Cafe (c. 1875–77), Edgar Degas. Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Take, for example, the Fitzwilliam’s enigmatic At the Café (c. 1875–77), depicting two unidentified women in hesitant conversation, seated at what we take to be a café table. Unfinished, the painting keeps us guessing. For Sickert, who saw the painting in London in 1922, it offered ‘a useful instance of a procedure of black and white dead-colour’, but comparison between the smeared, inchoate brushwork and a group of contemporary monotypes – some of his earliest experiments in ‘greasy ink’ printing – also points to aesthetic affinities that exemplify Degas’s tendency to maintain a degree of technical fluidity between the different media in which he worked. Then there is the question of identity: are these women prostitutes, as has sometimes been proposed? Or other forms of ‘working girl’ captured in a moment of café-based socialising? Arguably, and not just because their features are illegible, this matters little, for what seems to interest Degas more is the evidently tense nature of the dialogue that consumes them, but keeps them resolutely apart. Paintings and pastels borrowed for the show reveal Degas’s preoccupation with the psychological dynamics of conversation – both active and lapsed – whether between women at leisure or in more loaded scenes of gender-based inimicality in which conversation, if it ever existed, has been suspended.

Elisabeth de Valois (c. 1865–70), after Antonis Mor, Edgar Degas. Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

If there is a strand running through the exhibition, it is perhaps that of learning. Opening with a selection of works that show Degas studying and copying from artists he admired, and in some cases went on to collect – from early Renaissance artists and Dutch and Flemish masters of the 17th century to his idol, Ingres – the exhibition concludes with a section that explores Degas’s legacy among 20th- and 21st-century artists such as Sickert, Picasso, Auerbach, Bacon, Kitaj, Freud, Hodgkin, and Ryan Gander, who have drawn on Degas as he had done from artistic precedent, learning from his example while ‘doing something different’. Present throughout is evidence of Degas learning from and challenging himself, whether in the form of his multiple iterations of compositions and individual poses of dancers and nudes, obsessive reworking of paintings, sometimes to near-illegibility, or the speculative technical procedures and unconventional materials he adopted, notably to model his wax sculptures.

After Degas’s death, the temptation among his early biographers to unravel or explain the inner workings of his genius was strong. According to one, the dealer Ambroise Vollard, Degas’s decision to narrow his focus in later life and dogged reworking of a single motif was driven by his ‘passion for perfection’, as part of a wider commitment to pictorial ‘research’. A century on, his resistance to closure might equally be identified as a marker of his modernity, aligning it with the aesthetics of serialism and the non-finito, to which notions of ‘perfection’ seem alien. The exhibition presents the evidence, and leaves the visitor to decide.

‘Degas: A Passion for Perfection’ is at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, from 3 October–14 January 2018.

From the September 2017 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

Share

Recommended for you

‘Silent Partners’: mannequins at the Fitzwilliam Museum

How have artists used mannequins and dolls to manipulate their audiences?

First Look: ‘Degas / Cassatt’ at the National Gallery of Art, Washington

The curator’s introduction to the latest exhibition at the National Gallery of Art, Washington

The mysteries of collecting

They don’t make collectors like Francesco Federico Cerruti any more. Or do they?