Bringing together over 300 images, the Irving Penn centennial exhibition at the Met offers a dizzying run through the long arc of Penn’s career. The photographs include Penn’s earliest quasi-touristic photos of various signs and street scenes; vibrant still lives; his fashion photographs from the 1940s through the 1990s; endless portraits (the most notable of which are the celebrity portraits in which he boxed all his subjects quite literally into a corner for the photographs); a set of photographic ‘types’ of different European workers from the 1950s; distinctive ethnographic portraits from Peru, Benin, and Morocco; a group of radical nudes; and abstract photographs of street debris. Showcasing at once the sheer quantity of Penn’s production and the endless variety of his subject interests, the show presents a photographer who, though best known for fashion photography, was an artist with a profound awareness of the history of art and a desire to find photography’s place in that history.

Truman Capote, New York, 1948 (1968), Irving Penn. © The Irving Penn Foundation

But while the show emphasises quantity and variety, it is far more interesting for the unique opportunity it provides, simply by bringing Penn’s many different photographs together in one place, to understand the unity of vision that binds them together. Penn’s photographs are above all formal, not material, endeavours. His meticulously executed images, however precise, never wallow in the physical reality that the photograph replicates so perfectly. Nor do they abandon or fundamentally manipulate that reality; still, they manage to reorganise it so that the formal beauty of each subject is made evident. The most obvious example of Penn’s formalistic approach is his late series of street detritus, where the filth of cigarette butts and crumpled paper cups are transformed into abstracted shapes and textures in different shades of grey. His famous fashion photography offers an even more fascinating example of this formalism. What are ostensibly photographs of clothes, of beautiful women, of a luxurious and coveted physical reality, are actually studies of patterns, of gesture, of potential meaning that has nothing to do with the clothes for sale and everything to do with the play of light and dark on photosensitive paper.

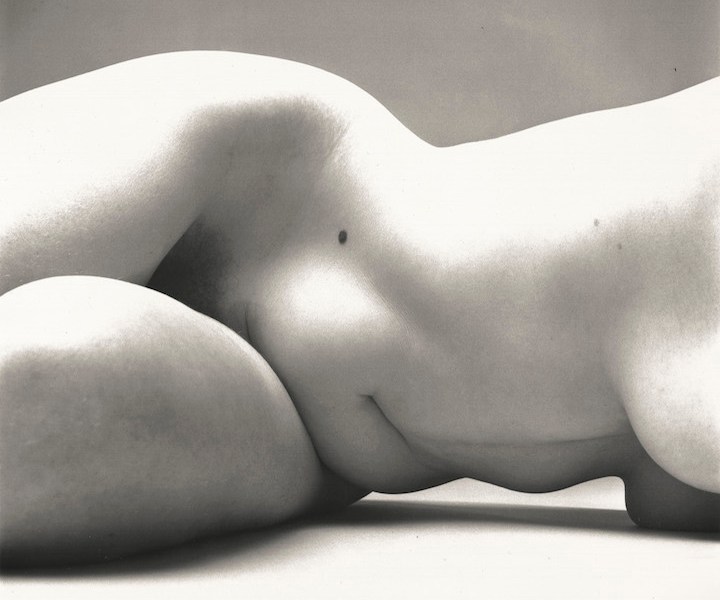

Nude No. 72, New York, 1949–50 Irving Penn. © The Irving Penn Foundation

The most controversial – and interesting – example of this formal approach is Penn’s series of nudes. Penn could not find an audience for these photographs when he made them, and it is easy to see why. They are at once too materialistic and too abstract. They neglect to veil the reality of the female body, yet they also defy realistic representational norms. They turn the weird and fleshy body into its own compositional principle; like it or not, Penn’s approach is radical, even revolutionary. In the history of aesthetics stretch back to Aristotle, the two competing forces at work in art, material reality and formal principle, had been hierarchised and gendered. Physical matter was figured as passive woman, waiting to ascend into meaning as it was moulded by masculine form. In Penn’s nude, the dichotomy disappears. The difficult reality of a woman’s (perhaps even slightly unseemly) body reveals its own formal principles. It, too, needs little more than to be transferred to photographic paper for these forms to be revealed.

Marlene Dietrich, New York, 1948 (2000), Irving Penn. © The Irving Penn Foundation

Penn’s formalism produces some astonishingly well-executed photographs – photographs that assert unequivocally that the camera is (to borrow Penn’s own formulation) as much a Stradivarius as a scalpel. Ultimately, however, the most remarkable quality of Penn’s formalism may lie less in the exalted realm of aesthetics to which it aspires than in the earthly realm of the reality it works to transform. This approach to photography could easily become cold or dehumanising, particularly when applied to the portraiture that makes up so much of Penn’s work. Instead, it is levelling. The only judgment made by Penn’s photographic eye is whether or not a subject will make a good photo, regardless of what that subject is. A nude or a still life; an anonymous Muslim woman veiled from head to toe, or Salvador Dali, it little matters. Each subject is equal in the eye of the camera, an outlook with just as significant human as aesthetic consequences.

Tribesman with Nose Disc, New Guinea, 1970 (2002), Irving Penn. © The Irving Penn Foundation

‘Irving Penn: Centennial’ is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, until 30 July.