This review of ‘Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Fly In League With The Night’ at Tate Britain, London, was published in the February 2021 issue of Apollo. The exhibition reopens on 17 May and will run until 31 May.

This sentence glitters on a wall at the entrance to Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s show at Tate Britain: ‘But the idea of infinity, of a life and a world of infinite possibilities, where anything is possible for you, unconstrained by the nightmare fantasies of others, to have the presence of mind to walk as wildly as you will, that’s what I think about most, that is the direction I’ve always wanted to move in.’ These are her own words, and they bear an extra shine given the literary branch of her art (poems, occasional prose, animal fables), and which, in their aspiration towards an existential liberty, convey the atmosphere of her paintings, their auras of cryptic distance yet bold, living presence, as if the act of creating them were the wish itself.

No Need of Speech (2018), Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. Carnie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh. Photo: Bryan Conley; © Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

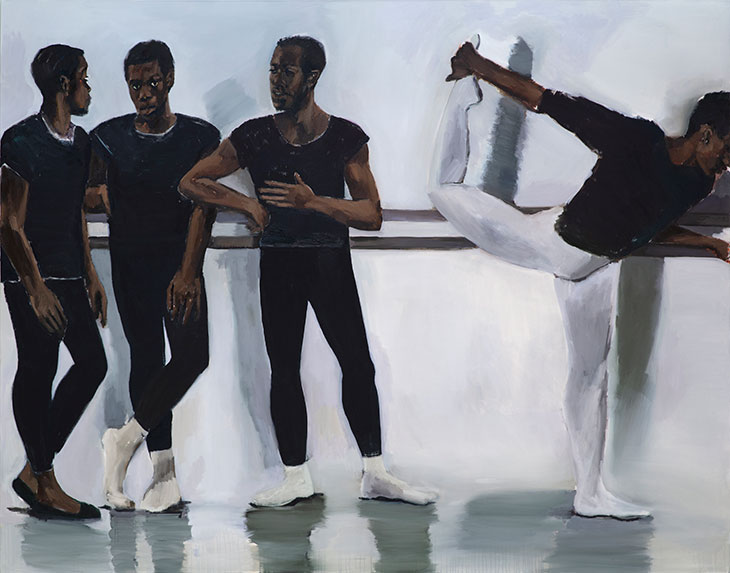

The figures in these paintings walk wildly, in their loose dark lines and muted landscapes, their casual gesture and gentle staring. Their thoughts are entirely their own as they look off into a dappled sepia with a touch of gold in it, such as the woman caught in contemplation in Penny For Them (2014), or sit troubled and fatigued in the diptych Pale For The Rapture (2016) with its contrasting stripe-check sofas. They hold council with birds, an owl perched in hand or a shockingly bright parrot glowing from the grip of a man’s enveloping gloom. Sometimes they are dancing, like the young men at the ballet barre in A Concentration (2018), or laughing or inwardly smiling, or looking directly at one another as the two boys in No Need of Speech (2018). This painting in particular evokes an emotional charge, given the routine negative reduction of black boys in mainstream representation, but Yiadom-Boakye wants to capture the subject beyond all that, in the freer, almost possible, infinite space. Her men, women and children, conjured from her imagination, have an air of something heavy having been thrown off. They are unconstrained by those ‘nightmare fantasies’ and allowed simply to live, to be; strident yet languid, close to joy. ‘I don’t like to paint victims,’ the artist has said.

A Concentration (2018), Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. Carter Collection. © Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

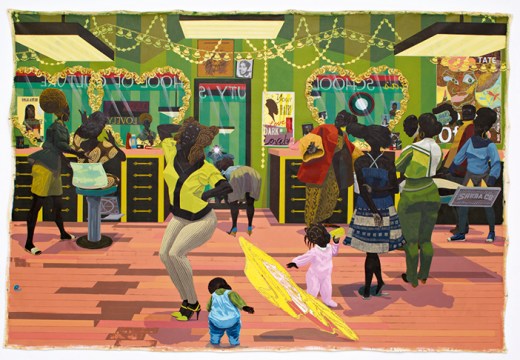

‘Fly In League With The Night’ is the first major survey of Yiadom-Boakye’s work, featuring some 80 oil paintings spanning nearly two decades, from her training at the Royal Academy Schools to recent pieces created in her east London studio and, in smaller scale, at her south London home during lockdown. The paintings, some on canvas, some on herringbone linen, are hung low for closer impact and unchronologically, instead arranged in communication with one another. There are the sharp, spectacular reds of the opening room where a brash, carnal early work, First (2003), is positioned next to the refined, yet no less imposing, subject of Any Number Of Preoccupations (2010) in his draping vermilion gown and white slippers (a direct nod to John Singer Sargent’s Dr Pozzi at Home); while adjacent lies a crimson-tongued fox beneath a stool on which a man sits, carefree and leaning forward, both welcoming and enclosed in darkness. Further on, a gathering of gentler, shadowy outdoor scenes with figures walking and talking, lounging on sand or silently looking out, give a calmer, more luminous effect; a highlight here is Condor and The Mole (2011), one of Yiadom-Boakye’s comparatively rare depictions of children, two black girls playing on a beach, the kind of rural image we have scarcely seen before in this style of painting.

Condor and The Mole (2011), Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London. © Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

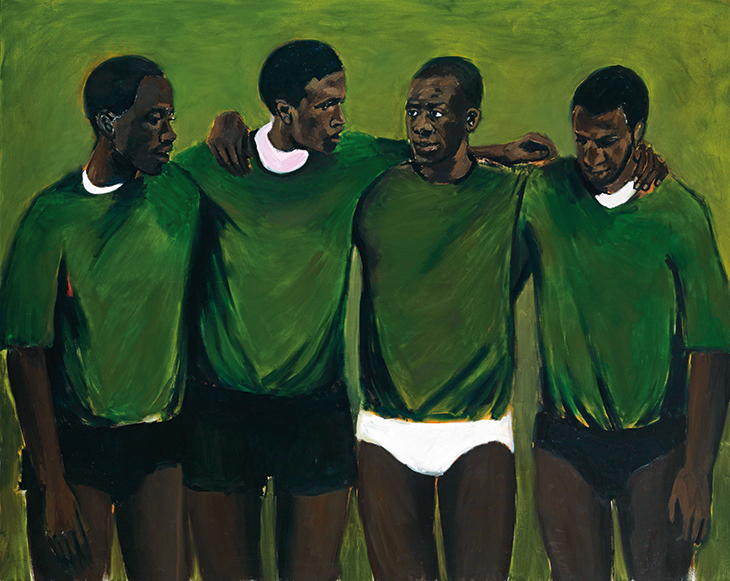

It is the absence of black subjects in traditional Western portraiture, from which Yiadom-Boakye draws much of her influence, that makes these paintings intrinsically revolutionary, but her approach to paint, her relationship to it, the way she makes it speak, is more the point. Her many darknesses are rich and hued, never hollow, faintly misted by a suggestion of green, within the green the yellow, the brown, or there is the dim stretch of night purple behind the bright hat feather of Six Birds In The Bush (2015), making the soft brown of the face and the beige of the eyes almost move towards you. With a flash of white she makes laughter come, or smoke drift. White dances monochrome circles on a T-shirt against the dark of 11pm Tuesday (2010), making fabric fly and lift around the slightly radiating figure, thereby making breeze, light, air. These endless adventures in colour play and signal and decide for themselves, the artist acting as a conduit. There are the pink and mustard ties in what I think of as the avuncular paintings – tenderly rendered depictions of ageing men clinking glasses or linking arms – and then the jubilant, never-ending greens of the four young men in Complication (2013), my personal favourite for its quiet humour and brotherly love.

Complication (2013), Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. Private collection. © Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

The titles of Yiadom-Boakye’s portraits are ‘an extra brush-mark’, she says, and can be thought of as bridges between her painting and her writing. There are no explanatory captions accompanying the images, only the possibilities mostly conjured by their names. Likewise the paintings are devoid of temporal specificities of attire or object or defined locales, and the subjects themselves are imagined beings rather than real, characters arrived at through a process of composition, begun without preliminary sketching or outline. These arrivals are made possible by the clearing of space; reality is stripped back so that the human figure might be captured in its immediate lucidity, unmarred by the dampening associations of societal identification and circumstance. Toni Morrison once wrote of the work of James Baldwin, ‘You gave us ourselves to think about’, and Baldwin being held dear by Yiadom-Boakye, this seems a fitting observation. She gives us ourselves to think about by drawing what has been held in shadow – misunderstood, ignored, unwitnessed – into the light of near transcendence. And she does not deny the shadow, but makes it part of the story, a site of permanent yet quietened resistance.

Yiadom-Boakye’s work is a triumphant demonstration of the power of the artist to recreate, reclaim and restore the world for the time of looking. I found it difficult to leave the kindness of this show, but the voice of the paint went with me.

From the February 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam got its rehang right?