In an obituary for Mainie Jellett (1897–1944) Elizabeth Bowen recalled, with some relish, witnessing the ‘opening of Mainie’s life as an artist’. Their families were neighbours in Dublin and the two girls had attended painting classes together, taught by art teacher and publisher Elizabeth Yeats (sister of W.B.) and convened in the Jelletts’ dining room. Almost 50 years later, Bowen was still ‘proud’ to be considered Jellett’s ‘contemporary’, but she added, rather wistfully, that ‘to have worked with her must surely have been a great thing’.

This ‘great thing’ was reserved for Evie Hone (1894–1955), another Dublin-born painter. Their companionship in art and life is the subject of the exhibition ‘Mainie Jellett and Evie Hone: The Art of Friendship’ at the National Gallery of Ireland. The women met in London, as students of Walter Sickert, in 1917, but the exhibition begins with their time in France in the 1920s. In 1921, the pair travelled to Paris to study under the Cubist André Lhote but soon found themselves attracted to the more outlandish forms of abstraction pioneered by Albert Gleizes. Jellett and Hone, then in their twenties, arrived unexpectedly at Gleizes’s apartment near the Bois de Boulogne. He was surprised, even rather alarmed, by their request for his tuition. It was only the obduracy of their ambition, and the gentleness that gilded it, that convinced him to take them on.

The first room in the exhibition testifies to the stylistic similarities between Hone and Jellett in these early years. Jellett’s 6 Elements (1926) is displayed next to Hone’s 4 Elements (1924). Both works use similar palettes of black, pastel pink and orange and are animated by geometric, angular patterning. Tellingly, Jellett later compared the atmosphere in Gleizes’s studio to ‘the old Italian’ workshops in which ‘the master and student worked together, sometimes on the same painting’. Hone and Jellett’s apprenticeships in abstraction suggest two artists spurred on by the same subversive impetus, with almost twinned talents.

Decoration (1923), Mainie Jellett. Photo: National Gallery of Ireland

Jellett’s Decoration (1923) is the best-known painting on display. The overlaid polygons at its centre are undeniably abstract but they are surrounded by a halo of gold leaf and the wood panel itself recalls the structure of an early-modern tabernacle. The shapes hint at the Madonna and Child. There are numerous paintings in the exhibition by both Hone and Jellett that display such devotional ingenuity. In Hone’s colourful Maternité (1932), a child-like shape is cradled in Cubist lines. Through the accomplished flatness of Jellett’s Deposition (Abstract) (1940), we can glimpse two figures poised like the Pietà. Both women were deeply spiritual; Jellett was Protestant, and though Hone briefly joined an Anglican convent, she converted to Catholicism in 1939. These religious works merge their modernist aesthetic with a more traditional subject matter. Initially, this synthesis, and its largely non-representational nature, proved an unwelcome import in Ireland. When Decoration was exhibited at the Society of Dublin Painters in 1923, it was decried by critics. An anonymous review in the Irish Times called it an ‘insoluble puzzle’. Days later, the paper suggested that perhaps readers ‘could provide a solution’ to Jellett’s riddling work.

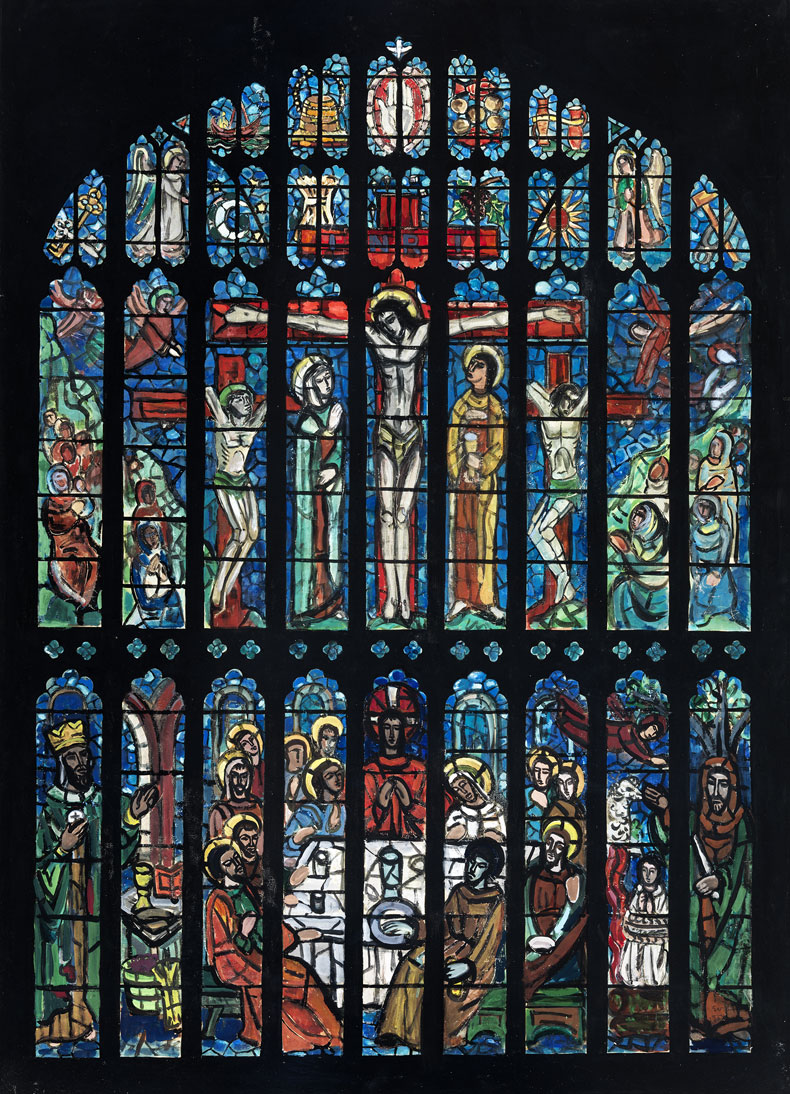

The next room, however, attests to Jellett and Hone’s sudden turn in fortune. As well as commercial commissions (including a folding screen and posters) there are commissions from the Irish state. Jellett designed murals to decorate Ireland’s Pavilion at the Glasgow Empire Exhibition of 1938. Her Map of Ireland (c. 1937) is a representation of Ireland’s industry, dotted with cars, barrels and an airplane. Though deftly detailed, its figurative forms flirt with caricature. Hone’s gouache-on-paper cartoon for My Four Green Fields (c. 1938) is more successful. It corresponds to a commission from the Irish government to design a stained-glass window to mark Ireland’s contribution to the World’s Fair in New York in 1939, and shows symbols of Ireland’s four provinces jostling for pictorial primacy in a riot of colour and shapes.

The Crucifixion (top), Melchizedek, the Last Supper and the Sacrifice of Isaac (bottom) (1950), Evie Hone, design for the east window of the chapel at Eton College, executed 1952. Photo: National Gallery of Ireland; © Geraldine Hone, Kate Hone and the FNCI

Hone is best known for her work in stained glass – an entire, darkened room in the exhibition is dedicated to her test panels, which gleam with gemlike colours. This alliance between the two avant-garde artists and their government would have been implausible a decade earlier but, by the late 1930s, independent Ireland was keen to nurse its international image as a progressive state. For Jellett and Hone, the commissions allowed them to reconcile the country to their radical art. Jellett in particular thought that the cloistered artist risked complacency and, in this light, both Hone and Jellett’s drift towards more figurative work in these years should be seen not as a concession but a change in tack. Their modernism remained, but became more cannily capacious.

Stained-glass panel, ‘The Cock and Pot’, or ‘The Betrayal’, c. 1947, Evie Hone. Photo: National Gallery of Ireland; © Geraldine Hone, Kate Hone and the FNCI

‘The Art of Friendship’ is the first joint exhibition of Jellett and Hone’s work since 1924. It is an ambitious collection of more than 90 artworks, spanning both women’s lifetimes, but by its end the conceit of their artistic companionship is tested. In Western Procession (1943), thought to be Jellett’s last painting before she died of cancer, her Cubist training is still legible, though relayed in a distinctly Irish idiom. These roots are harder to unearth in Hone’s late landscape paintings of Marlay in Dublin. The curators perhaps cling more keenly to her Cubist origins than Hone herself did. Nevertheless, the exhibition is a crucial reintroduction to Ireland’s modernist innovators, to their artistic affinities and their enduring friendship.

Snow at Marley (n.d.), Evie Hone. Photo: National Gallery of Ireland; © Geraldine Hone, Kate Hone and the FNCI

‘Mainie Jellett and Evie Hone: The Art of Friendship’ is at the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin, until 10 August.